How to identify, treat, and continue to manage patellar dislocations. Outlined by Emergency Medicine Residents and commented on by attending faculty at Northwestern Memorial Hospital.

Compartment Pressure Measurement: Using the Stryker Method

An overview of Compartment Pressure measurement using the Stryker Method.

Traumatic Arthrotomy

Written by: Parisa Kermani, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Alex Herndon, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Expert Commentary by: Matt Levine, MD

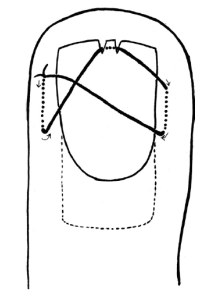

Case: A 25-year-old male comes into the ER after a saw accident at work. The patient was using a circular saw to cut wood when it slipped and the saw touched up against his knee. The patient has a 10cm linear vertical laceration over the anterior surface of his left knee (Figure 1). Bleeding is controlled. Patient ambulatory. Reporting 10/10 pain over the laceration.

What are the next best steps for evaluation and treatment of his injury?

Figure 1: Knee laceration

Background

Traumatic arthrotomy is defined as a soft tissue injury over a joint that penetrates the joint space. Violation of the joint capsule exposes the sterile intra-articular space to the environment which can result in a deep infection and sepsis. The morbidity associated with septic arthritis is high, so it is important that providers have a high index of suspicion when evaluating wounds over joint surfaces.

The knee joint is the most common joint to be affected, followed by the ankle. Penetrating injuries have a higher rate of capsule violation so a history of knives or bullets should raise suspicion, though MVCs, falls, motorcycle accidents can also result in a deep injury. The capsule has little protection lateral to the patella (Figure 2 & 3), so even if the laceration does not appear deep there is potential that it penetrates the joint space.

Figure 2: Knee capsule anatomy

Figure 3: Knee CT scan

Evaluation

Exploration: The first step of evaluation is local wound exploration. It is useful to anesthetize the wound at this point, as this will make the patient more comfortable and allow for a better exam. Irrigate the wound with sterile saline. It is extremely important to visualize the base of the wound. Using a hemostat or q-tip to probe the tissue at the base can be helpful as to not miss any tunneling segments. Keep a close eye out for bubbles, synovial fluid (appears straw colored and oily) or visible bone/tendon as all of these indicate joint involvement. It is important to note that the absence of these findings does not rule out a traumatic arthrotomy.

X-ray: Many times, next step will be to get an X-ray to look for associated fractures. Though this is not the most sensitive test for evaluating for joint space violation, if you see intra-articular air, this signifies joint involvement and no further imaging is required before calling the orthopedic surgeons. Many times, the X-ray will be normal and further testing will need to be completed. Of note, an x-ray is not required if there is no concern about injury to the bone as it is unlikely going to give a definitive answer on traumatic arthrotomy in less obvious cases.

CT Scan: As far as imaging goes, CT scan is the imaging modality of choice for traumatic arthrotomy. Though not currently the gold standard for ruling out joint violation, CT scan has become more accepted as an alternative to saline load testing the joint. Although limited, a 2013 study by Konda et al, where direct arthroscopic visualization or septic arthritis at follow-up were used as the gold standard for diagnosis, found imaging by CT scan to be 100% sensitive and specific for diagnosing traumatic knee arthrotomy. When viewing a CT scan to evaluate for traumatic arthrotomy, the presence of gas in the joint, known as pneumarthrosis, indicates intra-articular extension (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Traumatic arthrotomy on CT scan

Source: Konda et al, 2013

Saline Load Test (SLT): Though not strongly backed by the literature, SLT is a standard tool used to assess for traumatic arthrotomy. SLT is done by performing an arthrocentesis of the affected joint away from laceration, once confirmed in the correct space, sterile saline is injected into the joint and the laceration site is observed for extravasation. The provider should also passively range the joint while injecting to ensure greater sensitivity. Table 1 below summarizes how much sterile saline should be injected to obtain 95% sensitivity for traumatic arthrotomy. Adding methylene blue to the saline has not been proven to increase sensitivity and generally no longer recommended. The sensitivity will be highly variable based on provider experience with the procedure and patient tolerance. It is important to remember that this procedure can be exquisitely painful and special attention should be paid towards the patient’s comfort.

Table 1: Amount of saline for 95% sensitivity SLT

Because strong, conclusive literature is lacking, the choice between CT versus SLT to rule out traumatic arthrotomy will depend on many different factors including provider procedural comfort, local practice patterns, available resources and patient input.

Treatment

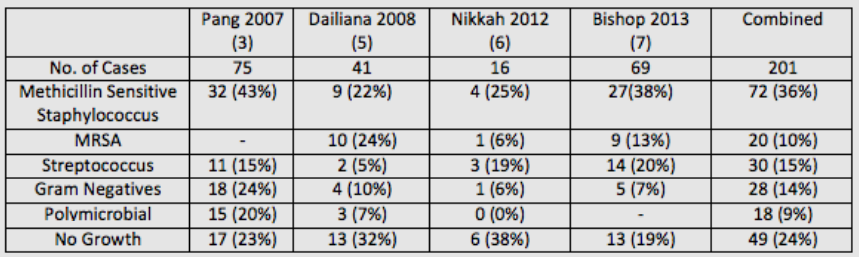

Once a diagnosis of traumatic arthrotomy is confirmed through an above modality, orthopedics should be emergently consulted. Tetanus prophylaxis should be updated and the patient should be started on an IV antibiotic that covers both strep and staph. A 1st generation cephalosporin is usually sufficient. Other antibiotics should be considered if injury is from a human/animal bite, happened underwater, or if there is concern for fecal/other contamination. Definitive treatment is joint wash out in the Operating Room.

If the above modalities do not show evidence of arthrotomy the patient’s laceration may be repaired in usual fashion. The patient should be given strict return precautions and have close follow-up for wound/joint reevaluation and suture removal.

Sources

Browning BB, Ventimiglia AV, Dixit A, Illical E, Urban WP, Jauregui JJ. Does the saline load test still have a role in the orthopaedic world? a systematic review of the literature. Acta orthopaedica et traumatologica turcica. 2016;50(6):597-600. doi:10.1016/j.aott.2016.01.004

Gittings D, Dattilo J, Fryhofer G, Martin A, Hast M, Mehta S. The saline load test is effective at diagnosing traumatic arthrotomies of the shoulder. Journal of surgical orthopaedic advances. 2019;28(4):268-271.

Gittings DJ, Fryhofer GW, Hast MW, Steinberg DR, Levin LS, Gray BL. The saline load test is effective at diagnosing traumatic arthrotomies of the wrist. Techniques in hand & upper extremity surgery. 2019;23(2):59-61. doi:10.1097

Jonathan Michael Strong. Saline Load or CT: What’s the Best Test for Traumatic Arthrotomy. Acepnow magazine. 2020; https://www.acepnow.com/article/saline-load-or-ct-whats-the-best-test-for-traumatic-arthrotomy

Konda SR, Howard D, Davidovitch RI, Egol KA. The saline load test of the knee redefined: a test to detect traumatic arthrotomies and rule out periarticular wounds not requiring surgical intervention. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2013;27(9):491-497. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e31828211f3

Konda SR, Davidovitch RI, Egol KA. Computed tomography scan to detect traumatic arthrotomies and identify periarticular wounds not requiring surgical intervention: an improvement over the saline load test. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2013;27(9):498-504. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e31828219bc

Metzger P, Carney J, Kuhn K, Booher K, Mazurek M. Sensitivity of the saline load test with and without methylene blue dye in the diagnosis of artificial traumatic knee arthrotomies. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2012;26(6):347-349. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182255167

Nord RM, Quach T, Walsh M, Pereira D, Tejwani NC. Detection of traumatic arthrotomy of the knee using the saline solution load test. The journal of bone and joint surgery american volume. 2009;91(1):66-70. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.01682

Timothy D. Roberts. Traumatic arthrotomy with pneumarthrosis on plain radiograph of the knee. Western journal of emergency medicine. 2016;17(2):184-185. doi:10.5811/westjem.2015.12.29317

Expert Commentary

What a great review of traumatic arthrotomy! You now have a concise reference that teaches you everything you would probably ever need to know about this tricky diagnosis! These injuries are so uncommon that the first hurdle to overcome is actually considering the diagnosis. If you don’t consider it, then you hopefully just get lucky by a diagnostic x-ray that was ordered for other reasons!

Physical exam and exploration is indeed important but has limitations and does not rule out the diagnosis if the suspicion is high enough. The tract may be small, jagged, or there may be soft tissue destruction that limits your visualization. Be sure to inspect the wound while passively ranging the joint in question since it is often unclear the precise position of the joint (fully flexed, fully extended, or somewhere in between) when the wound occurred. This may bring the wound tract into your field of view. Ideally your exploration should be in a bloodless, painless field and documented as such.

While x-rays lack sensitivity, they are a worthwhile starting point since they are less expensive, noninvasive, readily available, and you can stop if they are positive. X-rays may also better define the extent and trajectory of the wound tract which my either heighten your suspicion or provide reassurance that the trajectory was away from the joint.

If the diagnosis is still in question, I prefer CT in most scenarios. It provides additional information about any associated fractures. CT is painless. Intra-articular air is very easy to see on CT. The downside is increased cost. Saline load testing seems to have more room for error. The joint must be properly entered. Enough fluid must be injected to fill the joint enough to cause visible extravasation. And the diagnosis can still be missed if it is forgotten to range the joint during the SLT. It is also quite painful. Consider all the patients you see who present with a painful joint effusion that has gradually accumulated. In the SLT you are giving the patient a sudden acute joint effusion. Ouch! So just be thoughtful about the route you choose to go.

Matthew Levine, MD

Associate Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Kermani, P. Herndon, A. (2022, Apr 25). Traumatic Arthrotomy. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/traumatic-arthrotomy

Other Posts You May Enjoy

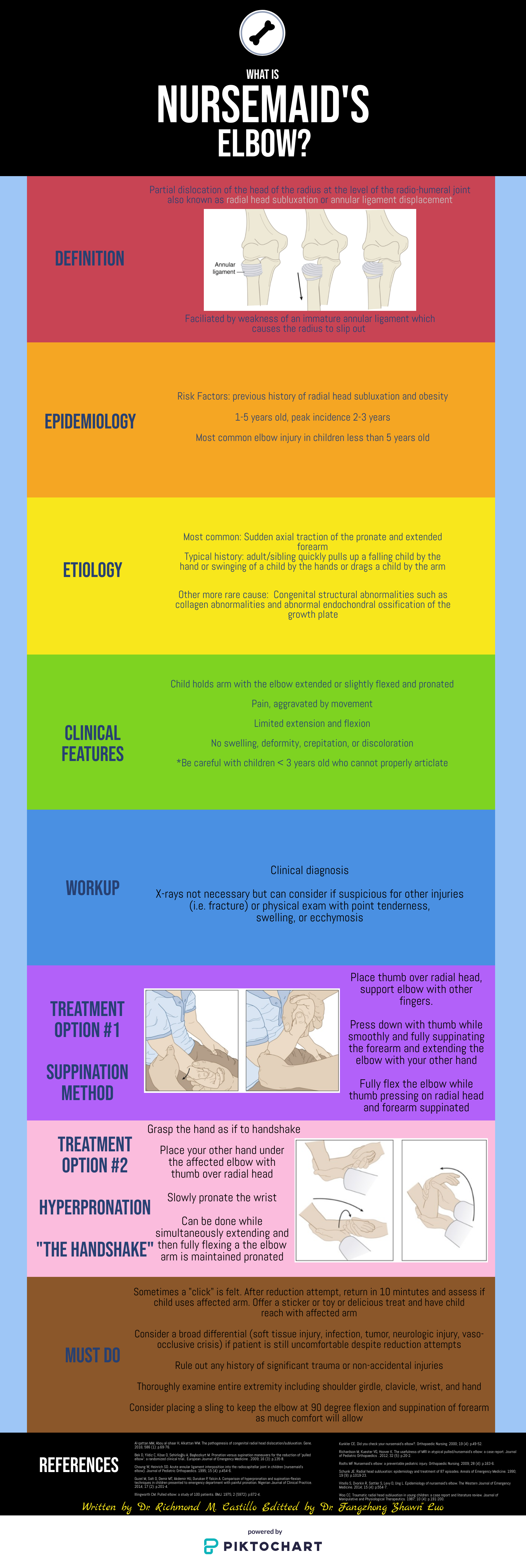

Nursemaid's Elbow

Written by: Richmond Castillo, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

Expert Commentary by: Jacob Stelter, MD (NUEM ‘19)

Expert Commentary

This is an excellent summary of the diagnosis and management of radial head subluxation (nursemaid’s elbow) in children. Clinically, as pointed out, these patients are usually toddlers and will come in after an injury to the arm. Usually, the clinical history will involve the child’s arm having been pulled on while the elbow was extended leading to sudden onset of pain and reduced mobility of the arm. The patient will most often be holding the elbow in flexion and be resistant to having it manipulated. In general, I have a low threshold to obtain radiographs on these patients. If the story and exam is classic for a radial head subluxation, imaging is technically not indicated, and reduction can be attempted. However, more often than not, the history can be vague, and the mechanism of injury may be unclear. In this situation, it is better to rule out a fracture first than to attempt a reduction without imaging. Attempted reduction could worsen or lead to displacement of a supracondylar humerus fracture if that is present. Keep in mind that it is not uncommon for the subluxation to reduce spontaneously during the process of obtaining x-rays.

There are two preferred techniques for reduction of a radial head subluxation. The method I start with is to support the patient's elbow and forearm and gently supinate the forearm while flexing the elbow and applying gentle pressure over the radial head. A “pop” sensation will often be felt as the radial head reduces. The other technique that can be used is to hyper-pronate the forearm while maintaining the elbow in a flexed position. Both of these techniques have a high success rate. Typically, the child will start using the arm again, but it may not be immediate. I will typically reassess the patient about 10-15 minutes post-reduction to ensure they are using their arm normally again. If the child is using their arm and able to extend and flex at the elbow without pain, they can be discharged, and no splinting is necessary. If no radiographs were obtained prior to reduction and the patient is not back to baseline post-reduction, x-rays should be obtained to rule out a fracture. Keep a broad differential, especially if the patient is not responding as you would expect or has other vital sign or exam abnormalities.

Jacob Stelter, MD, CAQ-SM

Division of Emergency Medicine | NorthShore University HealthSystem

NorthShore Orthopaedic Institute | Primary Care Sports Medicine

Clinical Assistant Professor | University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Castillo, R. Luo, F. (2022, Feb 7). Nursemaid’s Elbow. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Stelter, J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/nursemaids-elbow.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Running Injuries

Written by: Eric Power, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Justin Seltzer, MD (NUEM '21) Expert review by: Terese Whipple, MD (NUEM '20)

With over 40 million runners in the United States alone and an ever-increasing interest in fitness among the general population, the frequency of running injuries presented to urgent care and emergency departments will only grow with time. This is especially true due to the high rate of injury among runners, with a published annual incidence rate ranging from 19% to 79%; with even conservative estimates, that is nearly 8 million running injuries annually.

There are several risk factors for running injuries with which the emergency physician should be familiar. Running injuries are generally the sequela of repetitive stress. Acute injuries represent a small minority of cases and are usually not serious. The strongest risk factors include older age, high mileage running, beginners or suddenly restarting running, those making a rapid increase in speed and/or distance, low bone density, and those with a history of previous injuries.

This article will focus primarily on several “low acuity” running injuries along with their initial evaluation and management. A vast majority of running injuries are not serious, however, the evaluation of the injured runner still demands detailed musculoskeletal examination and thoughtful consideration of more dangerous potential causes of the symptoms. Proper clinical diagnosis and recommendations can certainly speed recovery and return to activity.

Iliotibial (IT) band syndrome

Major population: Young, active with a recent change in running mileage and/or runs on hilly terrain

Presentation: Lateral knee pain, especially with activity, with or without lateral thigh and hip pain

Diagnosis: Tenderness along lateral thigh extending into the lateral knee, swelling at the distal aspect may be present, Ober’s test for IT band tightness (not diagnostic)

EM differential: meniscus injury, stress fracture, lateral ligamentous injury

Initial treatment: No running until pain resolves then gradual return at painless speeds, distances, home exercise program to stretch IT band

Follow-up: Routine primary care, consider PT referral

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Major population: Young, usually female, participating in sports with high volume running and/or jumping

Presentation: Anterior, aching knee pain worse with knee flexion (e.g. climbing stairs)

Diagnosis: Anterior patella tenderness; pain with patellar grind test, deep knee flexion

EM differential: meniscus injury, stress fracture, ligamentous injury

Initial treatment: home exercise program or formal physical therapy to strengthen quadriceps, core, and hip abductors. consider a patella stabilizing knee brace

Follow-up: Routine primary care, consider PT referral

Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (“Shin Splints”)

Major population: Any patient with a recently initiated intense exercise regimen

Presentation: Anteromedial tibial pain provoked by activity and improved with rest

Diagnosis: Reproduction of pain with palpation of a diffuse area of the posteromedial border of the tibia

EM differential: stress fracture, DVT, exertional compartment syndrome

Initial treatment: Rest, icing (~20 minutes per hour) until the pain has resolved, then a gradual return to activity at painless speeds, distances

Follow-up: Routine primary care, consider PT, sports medicine referral due to high failure rate of conservative management

Achilles Tendinopathy

Major population: Usually middle-aged with recently initiated exercise or increased intensity/frequency

Presentation: Chronic, gradually worsening posterior heel and foot pain, often worst in the morning, with an impaired plantarflexion and explosive movements of the ankle

Diagnosis: Tendon palpation reproduces the pain, diminished range of motion and strength, calf muscle atrophy (late finding)

EM differential: calcaneal stress fracture, DVT, Achilles tendon rupture

Initial treatment: Reduce the intensity of activity to walking only until pain resolves, home exercise program to stretch and eccentrically load the Achilles tendon

Follow-up: Sports medicine and PT referrals due to benefit of rehabilitation and availability of multiple specialized therapies; some cases are treated surgically

Plantar Fasciitis

Major population: High volume or newly initiated/increased running or sports, slightly more common in women

Presentation: Classically plantar midfoot to heel pain worse with the “first step” in the morning

Diagnosis: Pain reproduced with palpation of the medial tubercle of the calcaneus and proximal plantar fascia, positive windlass test

EM differential: Foot stress fracture

Initial treatment: Avoid triggering activities, home exercise program to stretch and deeply massage the plantar fascia

Follow-up: Referral to PT and a foot and ankle specialist (orthopedic surgeon or podiatrist) as chronic symptoms are common

Key points

A majority of running injuries are not serious or acute but can be function limiting if not properly diagnosed and managed

It is important to rule out major relevant differential diagnoses such as stress fractures, DVT, and ligament/tendon injuries prior to discharge

Universal management is with rest, as needed NSAIDs, a gradual return to activity when the pain has resolved, and routine primary care follow up; primary care sports medicine or orthopedic surgery should be reserved for severe symptoms or failure of conservative management

Alongside home exercises and stretches, consider PT referral routinely

References

Li HY, Hua YH. Achilles Tendinopathy: Current Concepts about the Basic Science and Clinical Treatments. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:6492597.

McClure CJ, Oh R. Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538479/

Petersen W, Ellermann A, Gösele-Koppenburg A, et al. Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2264-2274.

Petraglia F, Ramazzina I, Costantino C. Plantar fasciitis in athletes: diagnostic and treatment strategies. A systematic review. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2017;7(1):107-118. Published 2017 May 10.

Strauss EJ, Kim S, Calce JG, Park D. Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Evaluation and Management. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon. 2011;19(12):728-736.

van der Worp MP, ten Haaf DS, van Cingel R, de Wijer A, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Staal JB. Injuries in runners; a systematic review on risk factors and sex differences. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0114937. Published 2015 Feb 23.

Expert Commentary

Thank you to Drs. Power and Seltzer for their concise and relevant review of common overuse injuries seen in runners. Although most of these injuries would not be considered emergent, correct diagnosis and referral of these patients is important to keep them active and decrease their likelihood of suffering the heart attacks, strokes, and chronic pain we see daily. This post did an excellent job of walking through several common injuries however, there is one more that I would like Emergency Physicians to consider in their differential for runners with extremity pain: Stress Fracture.

A stress fracture is break down in bone that occurs when abnormal stress is applied to healthy bone or normal stress is applied to unhealthy bone (osteopenia/porosis)

Female athletes are at particular risk if they are not fueling well enough, sometimes manifesting in menstrual dysfunction and decreased bone density

Commonly occurs in healthy runners when an athlete is increasing their training volume or intensity, or other new stress is applied such as a new running surface

Complain of insidious onset pain that worsens with running and other pounding activity. Pain is often better with rest early on.

If the bone is palpable from the surface, it will have point tenderness over the area. Pain will be reproduced with the hop test and the fulcrum test.

X-rays may be normal early on, later in the course, they may show periosteal reaction or fracture line. MRI can be obtained on an outpatient basis if needed.

Most stress injuries can be managed by decreased weight bearing through alterations in training, however, sometimes offloading with a walking boot or crutches may be necessary depending on severity and location.

High-risk stress injuries that warrant prompt sports medicine or orthopedics referral: femoral neck (superior aspect), patella, anterior tibia, medial malleolus, talus, tarsal navicular, the proximal fifth metatarsal, tarsal sesamoids.

If strong suspicion of a high-risk stress injury or diagnosis is confirmed in the ED, these patients should be given crutches and made non-weight bearing until follow-up.

Hopefully, this post will help you build a differential for overuse injuries you may encounter in the ED, and provide proper follow-up in order to keep our patients healthy, active, and engaged in the activities they enjoy.

Terese Whipple, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Power, E. Seltzer, J. (2022, Jan 3). Running Injuries. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Whipple, T]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/runninginjuries

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Hip Pain in Pediatrics

Written by: Tommy Ng, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Patricia Bigach, MD (NUEM ‘22) Expert review by: Terese Whipple, MD '20

So your kid won’t walk

One of the most common complaints in a pediatric Emergency Department is a child refusing or inability to ambulate. For normal development, a child is typically able to stand at 9 months, walk at 12 months, and run at 18 months. There is a certain degree of variability for these age constraints however any acute decrease in mobility should prompt an evaluation. A limp is defined as any abnormality in gait caused by pain, weakness, or deformity [1]. There are a plethora of conditions that can manifest with an antalgic gait or refusal to bear weight and it may be difficult to distinguish between etiologies given a child’s age.

History and physical

Age is an important factor as certain conditions are more likely depending on the patient’s age

Acuity should be determined as the chronicity of limp as certain etiologies are more acute while others are indolent. Additionally, certain infectious etiologies are more likely to present acutely or chronically.

Fever may suggest an infectious or rheumatologic cause

Trauma can help distinguish soft tissue vs orthopedic injuries

Past medical history is important to be focused on recent illnesses, antibiotic use, history of sickle cell disease, or hormonal diseases.

Physical examination should always include an attempt to ambulate the child unless there is an obvious contraindication noted immediately (eg open fracture). If the child refuses to bear weight, the child should be made non-weight bearing until serious pathology which can be worsened by walking is ruled out. Strength and range of motion of both lower extremities should also be examined [2].

Normal gait cycle (orthobullets.com)

Differential: the bad, the worse, and the ugly

Infectious

Transient Synovitis - Relatively common with a lifetime risk of 3%. Affects ages 3-8, males to females 2:1 [3]. Typically well appearing with normal labs, however, this is a diagnosis of exclusion and a septic joint should be ruled out. Management includes NSAID use and return to activity as tolerated [4].

Septic Arthritis - A “do not miss” diagnosis, commonly ages 3-6 with a slight male predominance [5]. Typically presenting with fevers and abnormal labs. The Kocher Criteria (originally developed in 1999 and validated in 2004) can be helpful in determining the likelihood of septic arthritis [6]. Management includes imaging studies, typical ultrasound to assess for a joint effusion, then a diagnostic arthrocentesis & antibiotics. The antibiotic regimen should be tailored to the child’s age and other predisposing factors to certain pathogens.

Osteomyelitis - Occurs in 1:5000-7700 kids in increased prevalence with MRSA communities; 2:1 male to female predominance with half of all cases occurring in ages less than 5 [7]. Commonly hematogenous spread from bacteremia; clinical suspicion should prompt radiologic evaluation. X-rays may be likely to be normal/inconclusive early in the disease course and MRI may be often indicated. Labs can be helpful but are not specific; a systematic review of >12,000 patients showed that elevated WBC was only present in 36% of patients [7]. ESR and CRP are non-specific but have a sensitivity of 95% [7]. Antibiotic therapy guidelines are similar to the management of septic arthritis. Surgical intervention may be indicated if there is a lack of improvement after 48-72 hours [8].

Osteomyelitis of the distal tibia (orthobullets.com)

Orthopedic

Legg-Calve-Perthes / Avascular Necrosis of the Hip - Age range 3-12 with a peak at 5-7, male to female ratio 3:1, can be bilateral in 10-20% of patients [9]. Radiographs should be obtained with high clinical suspicion but are often normal early in the course. An MRI would show fragmentation of the femoral head. The patient should be made non-weight bearing and be referred to a specialist. Children under 8 typically have a better prognosis however long-term management is poorly defined as there has been no long-term study [10].

Avascular necrosis of bilateral hip (orthobullets.com)

SCFE of left hip (orthobullets.com)

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis - Typically obese child, median age 12, bilateral in 20-40% of cases [11]. Presentation is classically chronic hip pain with antalgic gait however may present with knee pain. Physical exam classically shows external rotation and abduction of the hip during hip flexion. Management is orthopedic consultation for operative stabilization [12].

References

Smith E, Anderson M, Foster H. The child with a limp: a symptom and not a diagnosis. Archives of disease in childhood - Education & practice edition. 2012;97(5):185-193. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301245.

Naranje S, Kelly DM, Sawyer JR. A Systematic Approach to the Evaluation of a Limping Child. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Nov 15;92(10):908-16. PMID: 26554284.

Landin LA, Danielsson LG, Wattsgård C. Transient synovitis of the hip. Its incidence, epidemiology and relation to Perthes' disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(2):238-242.

Kermond S, Fink M, Graham K, Carlin JB, Barnett P. A randomized clinical trial: should the child with transient synovitis of the hip be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs?. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(3):294-299. doi:10.1067/mem.2002.126171

Bennett OM, Namnyak SS. Acute septic arthritis of the hip joint in infancy and childhood. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(281):123-132.

Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(12):1662-1670. doi:10.2106/00004623-199912000-00002

Dartnell J, Ramachandran M, Katchburian M. Haematogenous acute and subacute paediatric osteomyelitis: a systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):584-595. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28523

Kaplan SL. Osteomyelitis in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19(4):787-vii. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2005.07.006

Johansson T, Lindblad M, Bladh M, Josefsson A, Sydsjö G. Incidence of Perthes' disease in children born between 1973 and 1993. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(1):96-100. doi:10.1080/17453674.2016.1227055

Canavese F, Dimeglio A. Perthes' disease: prognosis in children under six years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008 Jul;90(7):940-5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20691. PMID: 18591607.

Herngren B, Stenmarker M, Vavruch L, Hagglund G. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):304. Published 2017 Jul 18. doi:10.1186/s12891-017-1665-3

Reynolds RA. Diagnosis and treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1999;11(1):80-83. doi:10.1097/00008480-199902000-00016

Expert Commentary

Thank you to Drs. Ng and Bigach for compiling a concise approach to a common chief complaint encountered by Emergency Physicians across the county: a child with a new limp or the refusal to bear weight.

The first step to this often-challenging problem is to try to localize the pain, and in non-verbal kiddos, this can be the most difficult task. As highlighted above, if the child is able, observe their ambulation and establish laterality of the limp and when it occurs during the gait cycle. Most of the disease processes we as Emergency Physicians are concerned about will cause an antalgic gait or a shortened stance phase. Shortening the stance phase decreases the amount of time that the child is bearing weight on the painful limb in an effort to decrease their pain. Sometimes this is so effective that their parents will observe a limp, but the child will not complain of any pain. A thorough exam of the back and lower extremities including inspection, palpation, and range of motion of all joints is also imperative for trying to localize the cause of their symptoms.

Let your exam and history guide lab evaluation and imaging, however, a good place to start is usually basic labs and inflammatory markers and a plain film of the affected joint. In some cases, you won’t be able to localize pain or exam findings at all, and a broad workup including plain film imaging of the entire extremity may be necessary.

A few additional pearls:

Always consider non-accidental trauma in children with new limp or refusal to bear weight.

Systemic symptoms such as fever should raise your suspicion for infectious etiology such as osteomyelitis or septic arthritis.

Classically children with transient synovitis will have had a recent viral illness, but this is not always the case.

Always examine the hips and consider hip plain films in children complaining of knee or thigh pain, but with a benign knee exam. They could be hiding an SCFE or Leg-Calve-Perthes disease.

Don’t forget to examine the SI joint, as it too can become infected or inflamed.

History of night pain should raise your antenna for malignancy like osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, or leukemia.

Consider Lyme arthritis in your differential for joint pain and swelling in endemic areas.

Ultrasound can be useful when evaluating for septic arthritis and transient synovitis and can be performed at the bedside. However, both septic arthritis and transient synovitis can cause effusion, and therefore it is not useful in differentiating between the two. (That’s where the Kocher Criteria should be used to risk-stratify and determine if joint aspiration and fluid analysis are warranted)

Ultrasound evaluation of a pediatric hip joint demonstrating effusion courtesy of Dr. Maulik S Patel (https://radiopaedia.org)

Finally, make sure that the parents understand the diagnosis, expected course, and follow-up plan. If the child continues to refuse to bear weight, their symptoms worsen or do not improve, or they develop new concerning symptoms such as new fever or new urinary retention, they should return to the Emergency Department or their pediatrician for re-evaluation. More than once I’ve had patients who seemed for all the world to have transient synovitis eventually be diagnosed with spinal cord tumor, chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, etc.

Terese Whipple, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Ng, T. Bigach, P. (2021, Dec 20). Hip Pain in Pediatrics. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Whipple, T]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hippainpediatrics

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Ankle Injuries

Written by: Eric Power, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Brett Cohen, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Expert Commentary by: Jake Stelter, MD (NUEM ‘19)

Stepwise Approach to Management of Ankle Injuries in the Emergency Department

Introduction

Ankle injuries are a common presentation to the emergency department. This group of injuries varies in severity with different treatments, discharge instructions, and follow up plans based on the injury classification.. Ankle fractures also have a large degree of variability in severity and require different initial management. In this post, we will focus on the most common types of ankle injuries and discuss the most important steps for initial assessment, management, and discharge instructions ED clinicians should be giving to their patients.

Ankle Sprains

A very common presentation of ankle injuries, especially for young athletes, is a patient coming in saying they “rolled” their ankle. This most often infers a mechanism of an inversion injury to the ankle, often after making a cut or sudden change in direction in a sporting event or landing on another competitor’s foot. In fact, it is estimated that 25% of all musculoskeletal injuries are inversion ankle injuries, and that half of all these injuries occur during sporting events. Sudden, forced inversion of the ankle, often while in slight plantar flexion, may result in injury to one or more ligaments of the lateral ankle ligament complex. The anatomy of this complex, from anterior to posterior, consists of the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), and the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL) [1].

Isolated damage to the ATFL is by far the most frequent injury after “rolling an ankle”, making up two-thirds of all cases. With increased amounts of inversion force there is injury to the CFL followed by the PTFL, which are involved in about 20% of cases [2]. However, as with almost all complaints that come into the ED, a focused history and physical exam is the most important initial step to assess and correctly diagnose an ankle injury. The exam should start with assessments of neurovascular status with pulses, sensation, and capillary refill. The ankle should also be examined for gross deformity, tenderness, swelling, range of motion (ROM), strength, and associated injuries of the foot or knee.

Assessing for other Injuries

It is also important to recognize that ligamentous injuries often do not happen in isolation. Studies have found the prevalence of concurrent bony injuries in patients with ankle sprains to be 15-21%, with an anterior talofibular avulsion injury being the most common type [3,4]. When trying to decide whether to image these patients with ankle pain and likely sprains to assess for bony injury, many EM physicians may be familiar with the Ottawa rules. The rules and several interactive clinical decision-making tools are available online. For review, if the patient meets any of the following criteria, they require imaging of the ankle to assess for bony injuries.

Tenderness at the distal 6cm of the posterior edge of the fibula or tibia

Tenderness at the tip of either malleolus

Tenderness at the base of the fifth metatarsal or navicular

Inability to take four steps immediately after injury and on initial evaluation in the Emergency Department

A recently conducted review by Beckenkamp et al. revealed these rules to be highly sensitive (99.4%), but poorly specific (35.3%) to rule out visible fractures on plain films [6].

If x-rays are negative for fracture, the patient still may require orthopedic follow-up, surgery, and have a longer recovery if there is concern for a syndesmotic injury, or “high-ankle sprain”. This is the result of an injury to the tibiofibular ligament and is further discussed in a post by Ford et al [7]. Important considerations when there is clinical concern for this injury include looking for bony overlap on the malleolar films and performing specific exam maneuvers such as a “squeeze test”.

Symptom Management

When deciding what analgesic to use, providers should use clinical gestalt. In order to limit the use of opioid pain medications to prevent dependence and other associated side effects, we recommend they are only used in severe injuries where the patient is in obvious, uncontrolled pain or after a trial of non-opioid pain medications has failed. It is also our recommendation that physicians should not hesitate to use NSAIDs for pain management in fractures without other contraindications, as overall there is limited evidence to suggest it impairs bone healing [8,9]. These medications also provide the benefit of reducing inflammation in patients with swelling and/or joint effusion.

Generally accepted principles to promote healing, decrease swelling, and reduce pain are frequently referred to as the acronym “RICE” or “PRICE”. PRICE is now preferred because it includes protection of the affected structures, along with the other classic teachings. The remainder of the useful acronym includes rest of the injured joint, using ice for 20 minutes on, followed by at least one hour off while there is still pain and effusion, wearing a compression sock or stocking to decrease swelling, and elevating the affected joint above the level of the heart when possible [10]. These strategies should be used in conjunction with anti-inflammatory medications as previously mentioned to provide symptomatic relief while the injury is healing, followed by a focused home exercise program or physical therapy, often after an evaluation and referral from their primary care physician.

For a mild ankle sprain, PRICE with encouragement of early weight bearing is the ideal management. Semi-rigid braces such as an ankle stirrup brace may be superior to an ace wrap [11]. For moderate ankle sprains, give the patient crutches and have them avoid weight bearing for 2-3 days after injury, with encouragement to begin crutch walking when they are able to tolerate it [12]. A common error in treatment of mild and moderate sprains is prolonged immobilization which may delay recovery, these patients should be encouraged to perform range of motion exercises at home. For severe ankle sprains, immobilize the patient in a splint and refer them to follow-up closely with Orthopedic surgery [13].

Summary and Recommendation of Steps in Evaluation of Ankle Injuries for the ED Physician:

Expose the joint

Focused history: mechanism, ability to ambulate immediately after injury, co-injuries

Physical examination of the ankle: with a focus on neurovascular status, gross deformity, swelling, point tenderness, ability to ambulate or bear weight, strength, and ROM of the joint

Physical examination of the rest of the extremity: Evaluate the foot, knee and tibia/fibula for associated injuries.

Analgesia: NSAIDs and acetaminophen, adjuncts if needed based on severity of injury and initial pain control

Imaging, if appropriate: recommendation to use tools such as the Ottawa Ankle Rule and Ottawa Foot Rule

Protection: ace wrap, air cast, walking boot up to splint and crutches, if needed

Discharge instructions for acute recovery (“PRICE”) from injury and follow-up appointment

References:

van den Bekerom MP, Kerkhoffs GM, McCollum GA, Calder JD, van Dijk CN. Management of acute lateral ankle ligament injury in the athlete. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013 Jun;21(6):1390-5. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2252-7. Epub 2012 Oct 30. PMID: 23108678.

Brostrom L (1966) Sprained ankles. V. Treatment and prognosis in recent ligament ruptures. Acta Chir Scand 132:537–550

Debieux P, Wajnsztejn A, Mansur NSB. Epidemiology of injuries due to ankle sprain diagnosed in an orthopedic emergency room. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2019 Sep 23;18:eAO4739. doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2020AO4739. PMID: 31553355; PMCID: PMC6905160.

Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, Ter Riet G (2003) Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ 326:417–423

Stiell IG, McKnight RD, Greenberg GH, McDowell I, Nair RC, Wells GA, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa ankle rules. JAMA. 1994;271(11):827-32.

Beckenkamp PR, Lin CC, Macaskill P, Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Moseley AM. Diagnostic accuracy of the Ottawa Ankle and Midfoot Rules: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(6):504-10. Review.

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Ford W, Li-Sauerwine S. (2019, May 27). Not All Ankle Sprains are Created Equal. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/high-ankle-sprain.

1. Adolphson, P., Abbaszadegan, H., Jonsson, U., Dalen, N., Sjoberg, H.E., Kalen, S. No effects of piroxicam on osteopenia and recovery after Colles’ fracture: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective trial. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 1993; 112: 127-130.

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Farcas A, Bode, J. (2020, April 6). Clinical Question: are we impeding our patients’ fracture healing by giving them NSAIDs? [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/fx-nsaids

Ivins D. Acute ankle sprain: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Nov 15;74(10):1714-20. PMID: 17137000.

Lardenoye S, Theunissen E, Cleffken B, Brink PR, de Bie RA, Poeze M. The effect of taping versus semi-rigid bracing on patient outcome and satisfaction in ankle sprains: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:81.

Birrer RB, Fani-Salek MH, Totten VY, Herman LM, Polit V. Managing ankle injuries in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1999;17(4):651-660.

Expert Commentary

This is a great review of ankle sprain injuries. Ankle sprains are one of the most common musculoskeletal injuries to present to the Emergency Department. From an emergency perspective, these injuries do not often require extensive intervention and are usually treated as discussed above with PRICE therapy. However, there are some important pitfalls to mention in regard to more serious injuries that can often be missed. The ankle joint is complex. It has multiple directions of motion and receives and distributes a lot of force and weight. It is the connection point between the lower leg and the foot, with multiple muscles and tendons originating in the lower leg, passing through the ankle and attaching to insertions on the foot. As a result of this anatomy, it is essential to not only evaluate the ankle, but to also pay attention to the foot and lower leg when evaluating an ankle sprain.

As pointed out, the most important first step in evaluating an ankle injury is to assess for neurovascular compromise and deformity. Dislocations or fractures causing neurovascular compromise require immediate reduction. Next, identifying the amount of swelling and ecchymosis is important. The more swollen and ecchymotic the ankle is, the more likely there is to be a severe injury. Palpation of the ankle is essential to guide further workup. Examining and palpating the base of the 5th metatarsal is important to evaluate for potential fractures to that bone. In addition, palpation of the entire fibula is important as well. External rotation injuries of the ankle can lead to syndesmotic sprains and a fracture of the proximal fibula called a Maisonneuve fracture. This will not be readily apparent on isolated ankle radiographs. In addition, I have a low threshold to image ankle injuries. Often when patients are in acute pain, it can be difficult to narrow down areas of tenderness. In addition, these patients will get x-rays if they follow up in an orthopedic clinic regardless.

My treatment of ankle sprains involves protecting the ankle, usually with an ace wrap and a stirrup ankle brace. I will provide crutches for non-weight bearing for the first 24 hours, after which I encourage patients to weight bear as tolerated. I also give instructions on ankle exercises to be done at home to prevent stiffness. For severe swelling or for high ankle sprains (discussed in a separate blog post), I will place the patient in a high rise controlled ankle movement (CAM) walking boot. Intermittent ice application for the first forty-eight hours definitely helps with swelling and pain, as does elevating the ankle when sitting. Compression stockings can be used, but are often painful. Hence, I prefer using an ace wrap for localized compression. Avoiding activities more intense than walking can worsen the injury and delay healing, so I typically tell patients to avoid running and returning to sports for a week or until reassessed, depending on the extent of injury. Reevaluation after a week with a sports medicine or orthopedic provider is beneficial to assess for healing, determine if further imaging, such as an MRI, is required, and begin rehab therapy.

Jacob Stelter, MD CAQ-SM

Division of Emergency Medicine

NorthShore Orthopaedic Institute

NorthShore University HealthSystem

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Power, E. Cohen, B. (2021, Nov 8). Ankle Injuries. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Stelter, J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/ankle-injuries.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Knee Dislocation

Written by: Andrew Rogers, MD, MBA (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Amanda Randolph, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: Matt Levine, MD

Introduction

Tibiofemoral dislocations are a relatively uncommon injury with high risk of morbidity to patients, and therefore represent an injury that the Emergency Physician should familiar with diagnosing and treating. The incidence of knee dislocation is quite low, representing approximately 0.02% of all orthopedic injuries. [1] Morbidity is high, with rates of vascular injury of 7-40%, neurologic injury of 5-40%, and amputation rates of around 12%. [2,3] Delays in identifying vascular injury >8 hours can result in higher rate of amputation approaching 86%. [3,4] Timely identification, treatment, and disposition directly impacts patient’s lives and limbs.

Anatomic Review

The knee is stabilized by ligaments, tendons, muscles, menisci, and cartilage. Figure 1 highlights key anatomic structures that stabilize the knee joint, including the major ligaments of the ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL. These ligaments, in various combinations, are disrupted in knee dislocations.

The neurovascular anatomy is also important to review and understand (Figure 2). The popliteal artery courses posterior to the joint and is tethered both proximally (at the tendinous hiatus of the adductor magnus) and distally (at the tendinous arch of the soleus muscle), making it susceptible to injury. [2] The sciatic nerve divides into the tibial and common peroneal nerves proximal to the popliteal fossa, with the common peroneal nerve tethered about the fibular neck. This attachment similarly increases the risk of common peroneal nerve injury. [2]

Figure 1: Structural Anatomy of the Knee [5]

Figure 2: Neurovascular Anatomy of the Knee [6]

Mechanism of injury

The mechanism of a knee dislocation can be high-energy, low-energy, or ultra-low energy. [2]

High energy: MVCs, falls from heights, crush injuries – ~50% of knee dislocations

Low energy: Sports injuries – ~33% of knee dislocations

Low energy: Falls from standing - ~10% of knee dislocations

Ultra-low energy: ADLs in morbidly obese (BMI >40) population [7, 8]

Classifications of Knee Dislocations

Two main classifications are used to categorize knee dislocations. [2] The Kennedy Classification defines the injury based on the direction of displacement of the tibia relative to the femur (Figure 3) The Schenck Classification is based on the pattern of ligamentous injury, with the Wascher modifications specifying lateral ligaments ruptured (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Kennedy Classification of knee dislocations with example illustrations [9]

Figure 4: Schenck Classification System with Wascher Modification [2]

ED Evaluation

Approximately 50% of knee dislocations spontaneously reduce so the Emergency Physician should maintain spontaneously reduced knee dislocation on their differential in all patients presenting with knee pain, especially for the obese patient with an ultra-low energy mechanism. [2, 3] Figure 5 is a summary diagram from Gottlieb, et al summarizing the algorithm for evaluation and management of knee dislocations.

Figure 5: Algorithm for the evaluation and management of knee dislocations in the Emergency Department [10]

History

Some historical details to inquire about include:

Mechanism of injury

Sensation of instability

Deformity at any point in time

History of injury or surgery to the joint

Timing of injury

Initial Physical Exam

As 50% of dislocations spontaneously reduce or due to an obese patient population, there may not be an obvious physical deformity. Key points to include (and document) on the physical exam include: [3, 10]

Gross deformity

Vascular exam

Assess for presence of dorsalis pedis and posterior tibialis pulses

Look for hard signs of vascular injury: pallor, coolness, pulsatile hematoma, pulsatile hemorrhage, palpable thrill, audible bruit, absent or diminished pulses

Neurologic exam

Sensory and motor deficits

Signs of common peroneal nerve injury:

Sensory deficit to lateral leg and dorsal foot

Inability or weakness in eversion and dorsiflexion of foot

Skin exam

Look for pinched, discolored, tented, or threatened skin

Assess for open dislocation or fracture

Bruising without effusion suggests capsule disruption – may hint toward dislocation [11]

Ligamentous laxity

May be limited by pain, effusion, or deformity

Compartments exam

In high-energy mechanisms, consider other injuries as a knee dislocation may be distracting, or consider careful examination of the knee if other injuries limit history (for example a head injury sustained in an MVC).

Initial imaging

AP and lateral radiographs of the knee

Recommended to also obtain radiographs of femur, tibia and fibula, as well as ankle and hip joints, although additional radiographs should not delay closed reduction if indicated, and may be obtained after reduction of the knee [11]

If patient cannot tolerate plain films, can consider urgent CT

Assess for dislocation and fractures (Figure 6)

Some subtle signs of spontaneously reduced knee dislocation include: [11]

Widening of medial joint space on AP film

Segond fracture – avulsion fracture of lateral tibial plateau which is frequently associated with ACL disruption (Figure 7)

Fibular head avulsion fracture (AKA arcuate fracture) – avulsion of LCL or arcuate ligament complex (Figure 7)

Figure 6: Lateral knee dislocation [12]

Figure 6: Posterior knee dislocation [13]

Figure 7: Segond fracture with red circle showing lateral tibial plateau avulsion fracture [14]

FIgure 7: Fibular head avulsion fracture with white arrow showing avulsed fragment [15]

Reduction

Once the diagnosis of knee dislocation is made, reduction should be attempted in the Emergency Department under adequate analgesia and conscious sedation. Early orthopedics consultation is recommended. Reduction technique requires at least two team members to perform, and involves reversing the mechanism of injury (Figure 8). [3, 10] One team member stabilizes the distal femur while the other team member provides in-line traction on the lower leg. If this is unsuccessful, then apply anterior or posterior pressure to the proximal tibia and/or distal femur with in-line traction still applied to facilitate relocation. Avoid applying pressure to the popliteal fossa, which may cause or worsen neurovascular injury. Some knee dislocations may not be reducible in the Emergency Department and may require open reduction by orthopedics in the operating room.

Figure 8: Technique for reduction of knee dislocation [20]

Post reduction

After successful reduction, splint in 20 degrees of flexion and/or use a knee immobilizer to stabilize the joint. [3, 10] Cut out windows in the splint to perform regular neurovascular checks. Prior to splint placement, consider full ligamentous examination while the patient is under conscious sedation prior to splinting to assess ligamentous injury.

Repeat evaluation of neurovascular status is imperative. Evaluation of peripheral pulses is key, but normal pulses may not rule out vascular injury due to collateral flow about the knee. [16, 17] An Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) should be obtained in all patients (Figure 9). An ABI is <0.9 has been shown to be 100% sensitive for vascular injury requiring operative repair. [3] Patients with an ABI >0.9 still require close monitoring and repeat exams.

Figure 9: Ankle brachial Index [18]

Some authors advocate for angiography in all knee dislocations while others advocate for angiography only in those with an abnormal ABI. [3, 17, 19] Given the time-sensitivity of a vascular injury threatening the limb, early consultation with vascular surgery in patients with concern for vascular injury is recommended. Vessel imaging should never delay operative intervention if indicated. [3]

Options for vessel imaging include:

CTA – quick and readily available in the ED with high sensitivity (95-100%) and specificity (99.7-100%) [10]

Direct or selective angiography – considered standard of care but is invasive and introduces risks of vessel cannulation.

Duplex ultrasonography – has good sensitivity (95-100%) and specificity (97-100%) but is operator dependent, may miss small intimal injuries, and availability may be limited. [10]

Disposition

Emergency surgery is indicated for:

Open dislocation

Irreducible dislocation

Ischemic limb

Vascular injury

Compartment syndrome

All patients not taken to the operating room for emergent exploration should be admitted for at least 24 hours of neurovascular and compartment checks. [3,10] The knee should be immobilized as described above, with the leg made non-weight bearing. If evidence of common peroneal nerve injury, will need ankle-foot orthotics and physical therapy. Nearly all knee dislocations will require eventual reconstruction 2-3 weeks post-injury with nerve exploration and repair as indicated at that time. [19]

Summary and Key Points

Knee dislocations are rare but significant injuries that require time-sensitive diagnosis and management.

There is high morbidity, with up to 40% vascular and/or nerve injury, and up to 10% leading to amputation.

Consider early consultation with orthopedic surgery and vascular surgery, as appropriate

Early closed reduction in the Emergency Department is key, with appropriate post-reduction immobilization

The neurovascular exam is critical, both pre- and post-reduction

All patients should have an ABI check post-reduction, regardless of the presence of a pulse, with vessel imaging pursued in those with abnormal ABI

All patients require admission for neurovascular and compartment checks

Expert Commentary

Thank you, Dr. Rogers, for providing an excellent comprehensive review of knee dislocations. Over the course of my career in the last 20+ years, imaging workup for knee dislocations has evolved substantially. It used to be dogma that all knee dislocations get traditional IR angiography. This was based on reports of undiagnosed popliteal artery thrombosis, where patients presented with a clinically and radiographically reduced knee and a palpable dorsalis pedis pulse that progressed to ischemic compartment syndrome and amputation. This paradigm has shifted because:

More recent studies indicate that the true incidence of popliteal artery injury is 7.5-14%. This is lower than initial older data suggested. [1, 2, 3]

The vast majority of intimal tears do not progress

CT angiography has emerged as a less invasive and highly sensitive option.

Emerging data have shown that observation periods for serial pulse checks and ABIs are highly sensitive for detecting clinically significant vascular lesions.

Remember that the first priorities in knee dislocations are rapid diagnosis and reduction. Reduction can restore absent pulses. Remember the algorithm provided by Dr. Rogers depends on what the vascular exam is AFTER reduction, not before.

Time sensitivity for those cases with vascular deficits cannot be emphasized enough. Delay dramatically affects outcome. Residual amputation rates post-surgery are 10%. [1] In cases of delay exceeding 8 hours, amputation rates have been reported to reach as high as 86%. [4] If required, on-table angiography in the operating theatre, rather than in radiology, has been reported to save 3 hours. [5, 6] So patients with ischemia/pulselessness after reduction need to be taken emergently to the OR, not to the CT suite.

Magnetic resonance (MR) angiography has been proposed as an alternative to define the vascular anatomy and diagnose asymptomatic vascular lesions, particularly as all these patients are likely to have MRI at some point to define the extent of ligamentous injury. In a small series of knee dislocations, findings were comparable to traditional angiography. Consider advocating for this when your consultant suggests CTA for patients with normal vascular exams and ABIs.

References:

Boisrenoult P, Lustig S, Bonneviale P, et al. Vascular lesions associated with bicruciate and knee dislocation ligamentous injury Rev Chir Orthop Traumatol, 9 (2009), 621-626.

Harner CD, Waltrip RL, Bennett CH, et al. Surgical management of knee dislocations J Bone Joint Surg Am, 86 (2004), 262-273.

Rios A, Villa A, Fahandezh H, et al. Results after treatment of traumatic knee dislocations: a report of 26 cases J Trauma, 5 (2003), 489-494.

Green NE, Allen BL. Vascular injuries associated with dislocation of the knee J Bone Joint Surg Am, 5 (1977), 236-239.

Lim LT, Michuda MS, Flanigan DP, Pankovich A. Popliteal artery trauma 31 consecutive cases without amputation Arch Surg, 11 (1980), 1307-1313.

Ottolenghi CE. Vascular complications in injuries about the knee joint Clin Orthop Relat Res (1982), 148-156.

Matthew R Levine, MD

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Rogers, A. Randolph, A. (2021, Feb 22). Knee Dislocation. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/knee-dislocation.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Rihn, et al. “The acutely dislocated knee: Evaluation and management.” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2004;12(5):334-346

Medina, et al. “Vascular and Nerve Injury After Knee Dislocation: A Systematic Review.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. September 2014. 472 (9): 2621-2629.

Boyce, et al. “Acute Management of Traumatic Knee Dislocations for the Generalist.” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.” December 2015. 23(12):761-768

Patterson et al. “LEAP Study Group: Knee dislocations with vascular injury: Outcomes in the Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) Study.” Journal of Trauma 2007;63(4):855-858

“Knee Diagram.” Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Knee_diagram.svg

Morcos, et al. “Popliteal lymph node dissection for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma: A case report of an uncommon procedure for an uncommon presentation.” World Journal of surgical Oncology. October 2011. 9(1):130

Azar, et al. “Ultra-Low Velocity Knee Dislocations.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. October 2011. 29(10):2170-4.

Vaidya, et al. “Low-Velocity Knee Dislocations in Obese and Morbidly Obese Patients” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. April 2015. 3(4).

Lasanianos, et al. “Knee Dislocations”. Trauma and Orthopaedic Classifications. Springer-Verlag London 2015. pp339-341.

Gottleib et al. “Evaluation and Management of Knee Dislocation in the Emergency Department.” The Journal of Emergency Medicine. November 2019. 58(1) 34-42.

Lachman, et al. “Traumatic Knee Dislocations: Evaluation, Management, and Surgical Treatment.” Orthopedic Clinics of North America. October 2015. 46{(4):479-93

Murphy, Andrew. “Lateral Knee Dislocation”. Wikimedia Commons. 20 May 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lateral-knee-dislocation-1.jpg

Duprey K and Lin M. “Posterior Knee Dislocation”. Wikimedia Commons. 2 February 2010. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PosteriorKneeDIsclocation.jpg

Ellisbjohns “Segond Fracture”. Wikimedia Commons. 2 November 2009. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SegondFracture.JPG

Thrush, et al. “Fractures Associated with Knee Ligamentous Injury.” Complex Knee Ligament Injuries, pp149-159. January 2019.

McDonough, E. and Wojtys E. “Multiligamentous injuries of the knee and associated vascular injuries”. American Journal of Sports Medicine. January 2009, 37 (1):156-9

Barnes et al. “Does the pulse examination in patients with traumatic knee dislocation predict a surgical arterial injury? A meta-analysis.” Journal of Trauma; Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. December 2002. 53(6):1109-14.

Jmarchn. “Ankle-Brachial Index” Wikimedia Commons. 14 February 2014.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pad_abi_ENG.svg

Fanelli, Gregory C. “”Knee Dislocation and Multiple Ligament Injuries of the Knee.” Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. December 2018. Issue: Volume 26(4), p150-152.

Henretig, et al. “Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins. 1997. P1098. https://aneskey.com/knee-dislocation-and-reduction/

Is Fracture Healing Impaired by NSAIDs?

Written by: Andra Farcas, MD (PGY-3) Edited by: Jessica Bode, MD (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Matthew Levine, MD

Clinical Question:

Are we impeding our patients’ fracture healing by giving them NSAIDs?

Why is this important?

Broken bones hurt. A lot. And we want to do something about that to make our patients feel better. In the context of the current opioid crisis and the controversy of prescribing opioids, we need good non-opioid alternatives. Enter NSAIDs. Multiple studies have investigated whether nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are efficient pain relievers in multiple scenarios, including fractures, and the consensus seems to lean towards yes. However, this is not a discussion about their effectiveness but rather an attempt to finally answer the question that emergency docs seem to have different answers to: will giving patients NSAIDs for their fracture-related pain actually lead to worse outcomes in terms of fracture healing?

Mechanism of action

NSAIDs work by inhibiting the COX enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins. In turn, prostaglandins work as inflammatory response mediators. When a bone is fractured, the healing process involves an inflammatory response. Giving NSAIDs alters that inflammatory response by decreasing prostaglandin production. This is why it’s been proposed that giving NSAIDs to patients with bone fractures will affect their healing.

Additionally, prostaglandins also modify the expression of bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), which are involved in the bone healing process. This is another mechanism by which NSAIDs may affect fracture healing.

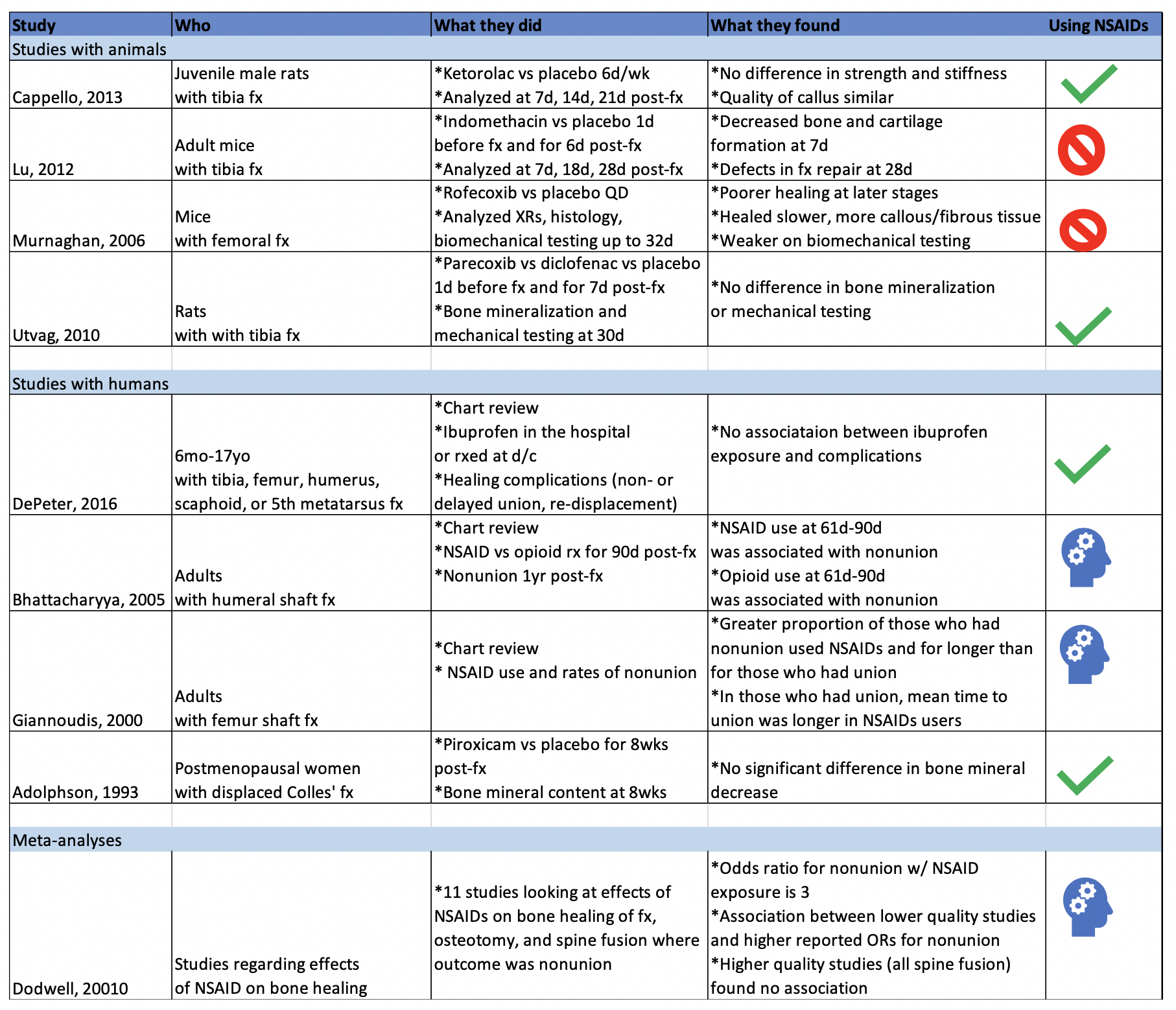

What the Research Shows

There have been a multitude of animal and human studies investigating the effect of NSAIDs on bone fracture healing, mostly in the orthopedic surgery community. The chart below has short summaries of some of the ones that are most relevant to emergency medicine.

Studies with Animals

Animal studies in general tend to use mice or rats with induced long bone fractures. The animals are exposed to NSAIDs or placebo and various bone characteristics are measured at various time frames. Capello, 2013 and Utvag, 2010 showed that Ketorolac, Parecoxib, and Diclofenac had no effect on strength, stiffness, or bone mineralization in rats with tibia fractures. On the other hand, Lu, 2012 and Murnaghan, 2006 showed that Indomethacin was associated with decreased bone and cartilage formation and that Rofecoxib was associated with slower and poorer healing in mice with tibia and femoral fractures, respectively.

Studies with Humans

While studies with animals have a lot of advantages, we’re often more interested in clinical outcomes than physiological nuances. DePeter 2016 in a retrospective chart review showed no association between ibuprofen exposure in kids with various fractures and healing complications like nonunion, delayed union, or re-displacement. However, there was no specification of the timeframe of treatment, and some patients received ibuprofen in the ED while others were sent home with it without a clear defined use period. Adolphson, 1993 showed there was no significant difference in bone mineral decrease in postmenopausal women with displaced Colles’ fractures that used Piroxicam for 8 weeks after the fracture compared to women who used a placebo. Giannoudis, 2000 found greater proportion of NSAID use in patients with nonunion of a femur shaft fracture compared to those who had union and found that in patients who had union, those who used NSAIDs took longer to achieve it. Bhattacharyya 2005 found that NSAID use at 61-90 days post fracture was associated with nonunion. However, an important thing to point out is that association does not equal causation. Is it that the NSAID use caused the poor outcome? Or is it that the poor outcome was more painful and thus those patients used pain medication for longer. To that point, Bhattacharyya, 2005 also found that there was an association between opioid use at 61-90 days and nonunion.

The Conclusion

The evidence isn’t slam-dunk in either direction on whether using NSAIDs impedes the fracture healing process. There aren’t many randomized control trials to explore causation (versus association) of NSAID use with fracture healing outcome. The one RCT I could find (Adolphson, 1993) leans towards no difference in outcome between NSAID users and placebo users. My takeaway: if my patients have no other contraindications to using NSAIDs and if their pain is well-controlled with said medication, then I’m going to advise they can use it for a short term and advise them to seek medical attention if they’re still needing to use NSADs regularly a few weeks out.

Expert Commentary

As is frequently the case in medicine, confounding factors make seemingly simple questions have not-so-simple answers.

Some animal studies suggested that NSAIDS can do harm to healing fractures. Others did not. The benefit of the animal study approach is that more variables can be controlled - the site of fracture, NSAID type, dose, frequency, duration of therapy. These animals were also surely more compliant with medications and follow up than our patients. However, animal studies do not necessarily translate to human outcomes. And these animal studies were less than definitive anyway.

The human studies were also less than definitive. Human studies are difficult for many reasons. Do NSAIDS affect pediatric, adult, elderly bone healing outcomes the same? Does it matter which NSAID, how often it is taken, the dose, the duration of use, which bone is fractured? When taking all these factors into consideration, it becomes more clear just how unclear the answer to this question is.

So at the end of the day, we do what we do time and time again in medical decision making – a risk-benefit analysis:

Option 1: Give NSAIDS. Risk causing an uncertain NSAID-related complication such as poor bone healing or a known NSAID complication such as a cardiovascular/GI/renal issue. Avoid narcotics.

Option 2: Give acetaminophen. Little downside as long as the patient can follow the directions you give them or on the bottle to avoid overdosing. Avoid NSAIDS and narcotics.

Option 3: Give narcotics. Avoid complications of NSAIDS. Expose to complications of narcotics. I don’t need to list these.

Option 4: Some combination of options 1, 2, and 3 because your gestalt is telling you that acetaminophen or NSAIDS alone won’t cut it for some cases.

I have different patients that end up falling into each of those options. This also raises another question - how do NSAIDS, acetaminophen, and opiates compare to each other for control of fracture pain? These scenarios and questions again demonstrate that medicine is often not a robotic one-size-fits-all, one-answer-to-every-question field, or else Dr. Google would replace us. Until more definitive RCTs come along, you will be required to use your judgment, or as I like to call it, expertise.

Matthew Levine, MD

Associate Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern University

How to Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Farcas A, Bode, J. (2020, April 6). Clinical Question: are we impeding our patients’ fracture healing by giving them NSAIDs? [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/fx-nsaids

Other Posts You Might Enjoy…

References

1. Adolphson, P., Abbaszadegan, H., Jonsson, U., Dalen, N., Sjoberg, H.E., Kalen, S. No effects of piroxicam on osteopenia and recovery after Colles’ fracture: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective trial. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 1993; 112: 127-130.

2. Bhattacharyya, T., Levin, R., Vrahas, M.S., Solomon, D.H. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs and Nonunion of Humeral Shaft Fractures. Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Care & Research), 2005; 53(3): 364-367.

3. Cappello, T., Nuelle, J.A.V., Katsantonis, N., Nauer, R.K., Lauing, K.L., Jagodzinski, J.E., Callaci, J.J. Ketorolac Administration Does Not Delay Early Fracture Healing in a Juvenile Rat Model: A Pilot Study. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 2013; 33(4): 415-421.

4. DePeter, K.C., Blumberg, S.M., Becker, S.D., Meltzer, J.A. Does the use of ibuprofen in children with extremity fractures increase their risk for bone healing complications? The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 2017; 52(4): 426-432.

5. Dodwell, E.R., Latorre, J.G., Parsini, E., Zwettler, E., Chandra, D., Mulpuri, K., Snyder, B. NSAID Exposure and Risk of Nonunion: A Meta-Analysis of Case-Control and Cohort studies. Calcific Tissue International, 2010; 87: 193-202.

6. Giannoudis, P.V., MacDonald, D.A., Matthews, S.J., Smith, R.M., Furlong, A.J., De Boer, P. Nonunion of the femoral diaphysis: the influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 2000; 82-B(5): 655-658.

7. Lu, C., Xing, Z., Wang, X., Mao, J., Marcucio, R.S., Miclau, T. Anti-inflammatory treatment increases angiogenesis during early fracture healing. Artchives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 2012; 132: 1205-1213.

8. Murnaghan, M., Li, G., Marsh, D.R. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug-Induced Fracture Nonunion: An Inhibition of Angiogenesis? The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 2006; 88-A(3): 140-147.

9. Utvag, S.E., Fuskevag, O.M., Shegarfi, H., Reikeras, O. Short-Term Treatment with COX-2 Inhibitors Does Not Impair Fracture Healing. Journal of Investigative Surgery, 2010; 23: 257-261.

10. Yates, J.E., Shah, S.H., Blackwell, J.C. Do NSAIDs impede fracture healing? The Journal of Family Practice, 2011; 60(1):41-42.

Can't Miss Hand and Wrist Fractures in the ED

Written by: Justine Ko, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: Spenser Lang MD (NUEM Alum ‘18 ) Expert commentary by: Matt Levine, MD

“Can’t Miss” Hand and Wrist Injuries in the ED

In the emergency department, orthopedic complaints make up a large percentage of presentations, up to 50% in the pediatric population and close to 33% in the adolescent and young adult population. Many of these injuries are uncomplicated, but an astute clinician can diagnose subtle and uncommon injury patterns. Three less common injuries are reviewed here. If found, these injuries can alter the management and disposition of the patient. Each of these injuries should be carefully assessed for on physical exam and imaging.

DISTAL RADIOULNAR JOINT (DRUJ) INJURIES

What exactly is the distal radioulnar joint and why is it important?

The distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) consists of both the bony radioulnar articulation as well as the soft tissue components, including ligaments. It has significant contributions to the axial load-bearing capabilities of the forearm. The injury can be an isolated injury or associated with forearm fractures and should be tested for with every forearm injury as its presence can alter the disposition and even functionality of the patient.

When does it occur?

A DRUJ injury may occur, although rarely, in isolation. This is usually related to a fall on outstretched hand (FOOSH). A DRUJ injury is more often associated with a fracture. Common associations include:

Distal radial fracture (DRF)

DRF + DRUJ = Galeazzi fracture (pictured to the right)

Ulnar styloid fracture

How should I assess for a possible DRUJ injury?

Routine AP and lateral views are poor for determining a DRUJ injury. This is largely a CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS.

Piano Key Sign: with the patient’s hand in pronation, push on the dorsal aspect of the ulnar head. Depression and rebound of the ulnar head suggest DRUJ instability

Table Top Test: have patient place hands on a table and apply force. A DRUJ injury will show dorsal depression of the ulna

Grind Test: hyperextend the wrist and axial load the forearm. A positive sign elicits pain over the joint

How does this alter management?

When associated with a fracture, operative management is often indicated and consultation with our orthopedist is warranted. When missed, a DRUJ injury will result in instability of the joint and arthrosis.

PERILUNATE AND LUNATE DISLOCATIONS

It has been reported that these injuries are missed in up to 25% of ED presentations.

How do these injuries occur?

In perilunate and lunate dislocations, the mechanism is usually hyperextension in the setting of trauma. Patients presents with hand and wrist pain/swelling.

How do I distinguish perilunate from lunate dislocations?

Lunate and perilunate dislocations can be easily confused or mistaken for each other. The key to distinguishing these injuries on imaging is the alignment between the metacarpal, carpal, and the radius/ulna bones.

In a normal lateral x-ray, these bones should all align (Figure 1, far left). In a lunate dislocation, the lunate itself is physically removed or out of line with the rest of these bones (Figure 1, far right), resulting in the classic “spilled teacup” appearance on x-ray. In a perilunate dislocation, the lunate sits in line with the radius/ulna, however the capitate/metatarsal bones are dislocated dorsally.

On an AP film, a break in Gilula’s arc/lines may be used to assess for a perilunate or lunate dislocation (Figure 2).

How Are These Injuries Treated?

In the ED, closed reduction can be attempted. If successful, definitive treatment can occur up to 7 days later. If unsuccessful, operative management is indicated. Definitive treatment involves open reduction and internal fixation.

How Would I Reduce These Injuries in the ED?

Usually, the assistance of our orthopaedic colleagues is warranted. Finger traps can be used for traction. The wrist should be extended while placing palmar pressure on the lunate. Then, with continued traction, the wrist should be gradually flexed so that the capitate falls back into place within the concavity of the lunate. Once the lunocapitate joint is reduced, the wrist can be extended in traction again for full reduction.

SCAPHOLUNATE DISSOCIATION

What is a scapholunate dissociation?

Scapholunate dissociation is caused by injury to the scapholunate ligament. Injury to this ligament can occur with acute FOOSH injury or be caused by degenerative rupture of the ligament.

How do I diagnosis it?

These patients present with radial wrist pain. On imaging, the following signs can aid in diagnosis.

Terry Thomas sign: This is seen on an AP wrist film and is indicated by a gap >3mm between the scaphoid and lunate bones