Written by: Kevin Dyer, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: Adnan Hussain (NUEM Alum ‘17) Expert commentary by: Aviram Giladi, MD

Case Presentation

A 29 year old right-handed male with no significant past medical history presents to the ED with left hand pain for the past 4 days. He reports that the pain started in the MCP joint of his left 2nd digit and was just “achy” at first, a mild 3/10. He noted associated swelling and erythema over the joint as well. Symptoms slowly became worse and he went to an urgent care facility yesterday where he was diagnosed with gout and sent home with NSAIDs and Norco. Overnight the pain became markedly worse, 8/10, and he began having subjective fevers. He denied any trauma to the area, no history of gout, no immune compromising diseases or medications, and no IV drug use. In the ED his vitals were stable and he was afebrile. He appeared uncomfortable. His left 2nd digit had fusiform swelling, pain with passive extension, tenderness to percussion along the flexor sheath, and was held in slight flexion at rest. The MCP was noted to be erythematous with the erythema extending to the palmar surface of the hand.

Background

This patient’s exam was concerning for flexor tenosynovitis (FTS), an infection of the flexor tendon and its synovial sheath that can result in deformity, tendon necrosis and adhesions leading to loss of function, or loss of limb, especially if treatment is delayed [1]. The flexor tendon sheath consists of visceral and parietal layers and functions to provide a gliding surface and nutrition to the extrinsic tendons of the digits. Once bacteria are inoculated into the space between the two layers, the synovial fluid becomes a medium for bacterial growth and the closed nature of the sheath limits the host’s immune response to fight infection [2].

Most patients with FTS will endorse a traumatic injury occurring 2-5 days prior to ED presentation [2]. Pang et al noted that 57 of their 75 patients (76%) with flexor tenosynovitis were caused by a traumatic event [4]. Of these, 81% were caused by a puncture wound. Often times, the inciting injury may have been trivial and patients may not endorse an event. Therefore, it is incredibly important to still consider the diagnosis of FTS even if a traumatic component is missing from the patient’s history.

Patients should be asked about associated symptoms such as fever, chills, anorexia, and malaise. Additionally, questions assessing the patient’s handedness, immune status, proximal extent of the pain, and other sites of pain should also be asked.

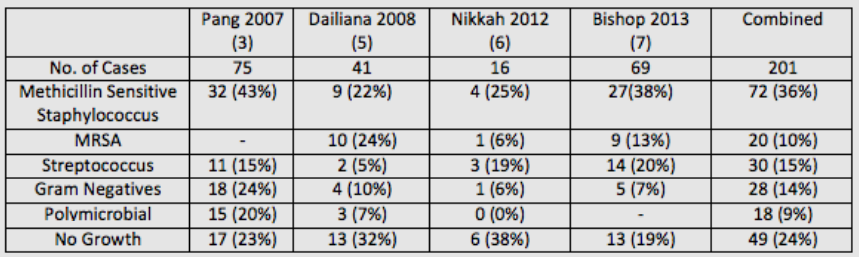

Microbiology

The most likely causative bacteria for FTS are skin flora. A review of four studies published within the past 10 years showed that out of 201 cases, 92 (46%) were caused by Staphylococcus with 20 (10%) being methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus(MRSA). Streptococcus species were the cause of 30 cases (15%), gram negative bacteria were the cause of 28 cases (14%), and 18 (9%) were olymicrobial. Interestingly, 49 (24%) cases of confirmed FTS were culture negative, which has been attributed to early use of intravenous antibiotics or an aggressive immune response [4].

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of FTS is based on the work of Dr. Allen B. Kanavel who described the four cardinal signs as:

Fusiform swelling.

Pain with passive extension of the digit.

Tenderness over the flexor sheath.

The digit held in slight flexion at rest.

No published study has validated the sensitivity and specificity of Kanavel’s signs, nor has there been a study validating inter-observer reliability. However, several studies have looked at the presence of the individual signs in patients diagnosed with the condition. Studies published by Pang et al and Nikkah et al had a combined 91 patients [3,6]. The most common sign was fusiform swelling and was present in 89 of 91 patients (98%). The second most common was pain on passive extension (73%), followed by tenderness over the flexor sheath (67%), and finger held in slight flexion (67%). Dailiana et al reported that only 54% of their 41 patients exhibited all four of Kanavel’s signs [5]. However, all of their patients displayed tenderness over the flexor sheath, which has been described by several authors as the most important sign when distinguishing FTS from other infections of the hand [4,5,8,9].

Image from EM in 5, used with permission from Anna Pickens, MD (10).

Work up for patients with suspected FTS should include plain films to rule out a retained foreign body and fractures [2]. Laboratory studies should include white blood count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Bishop et al studied 71 patients with clinically diagnosed FTS, 69 of which were confirmed by operative findings or positive intraoperative cultures [7]. All 69 patients had elevation of at least one of the three inflammatory markers, a positive predictive value of 100%. They reported negative predictive values for WBC, ESR and CRP as 4%, 3%, and 13%, respectively. The two patients without FTS were diagnosed with calcific tendinitis, both patients had normal inflammatory markers. These results suggest that a positive inflammatory marker when FTS is suspected makes the likelihood of infection extremely high. However, normal inflammatory markers cannot reliably rule out an infection.

Treatment

The two cornerstones for treating FTS are prompt administration of IV antibiotics and emergent hand surgery consultation. Antibiotic treatment should be guided by local antibiotic susceptibilities as well as the mechanism of infection. As discussed above, Staphylococcus, including MRSA, and Streptococcus species account for 61% of FTS cases whereas an additional 23% of cases are caused by gram negatives or are polymicrobial. Therefore, broad spectrum antibiotics are required. A common approach is to use vancomycin with piperacillin/tazobactam [2]. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist or a clinical pharmacist should be considered for patients with antibiotic allergies, immunocompromise, or chronic infections.

Learning Points

FTS can cause a loss of hand function or a loss of limb if treatment is delayed.

Patients may not endorse a traumatic event and the diagnosis must still be considered despite this.

The clinical diagnosis of FTS is made using Kanavel’s Signs:

Fusiform swelling.

Pain with passive extension of the digit.

Tenderness over the flexor sheath.

The digit held in slight flexion at rest.

Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species account for 61% of infections.

The two cornerstones of treatment are:

Broad antibiotics – Vancomycin and Zosyn is sufficient

Emergent Hand Surgery Consultation

Expert Commentary

Thank you for putting together this nice case report. Hand infections are common, and the challenge for the emergency provider is in deciding which patients are appropriate for a surgical consult (and for the surgery team, deciding which patients need surgery). In the era of strong IV antibiotics, the timing and indications for intervention are shifting. With early intervention using strict extremity elevation (hanging from the ceiling if possible) and IV antibiotics, we are avoiding surgery for some patients. This includes some with early FTS, before all of the Kanaval ’cardinal signs’ are evident. IV antibiotics have made it so that some patients with FTS, a condition traditionally considered to require surgery, are able to avoid surgery altogether. Maintaining a high index of suspicion for these problems is important in seizing these opportunities.

When specifically thinking about FTS, the notable challenge is that most patients (around 50% or more, as highlighted in the Dailiana article review) will present with only one or two ‘cardinal’ findings. Identifying any potential inciting event – whether small puncture, cut, or even working in the garden – helps to increase your index of suspicion. As the case highlights, many patients have a red joint, hand pain, or other presenting complaints that muddy the picture. The obvious FTS patients are relatively easy to identify, but the other 50% or more can be very challenging to diagnose.

Many infection, gout, arthritis flare, “hand that’s swollen and red”, etc. patients have such pain that a good exam is difficult. But, deciding on one of the four types of hand infection surgical emergencies – abscess, septic arthritis, purulent FTS, or necrotizing fasciitis – is critical. If the patient will not tolerate passive extension of the finger, my preferred way to evaluate for FTS without being unnecessary cruel is by manually compressing the tendons in the distal 1/3 of the volar forearm. You can try this on yourself – let your arm relax and then squeeze your forearm at the junction between the middle and distal 1/3 (where flexor tendons start to become distinct from muscles) and you can make your fingers flex; relax on the forearm and they will return to resting posture. If that maneuver creates focal pain in the swollen finger, my concern for FTS goes up.

Overall, high index of suspicion is critical. Rule FTS out, not in – convince yourself the patient doesn’t have a potential surgical problem by doing whatever evaluation and early treatment you think is appropriate and following the course, rather than delaying intervention until the presentation is more obvious. And, whenever in doubt, keep the patient NPO and consult a specialist so that a treatment plan can be put together without unnecessary delay or risk.

Aviram Giladi, MD, MS

The Curtis National Hand Center, MedStar Union Memorial Hospital

How to Cite this Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Dyer K, Hussain A (2019, January 28). Flexor Tenosynovitis [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Giladi A]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/flexor-tenosynovitis.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Kennedy CD, Huang JI, Hanel DP. In brief: Kanavel’s signs and pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.ClinOrthopRelat Res 2016;474:280–4.

Hyatt MT, Bagg MR. Flexor Tenosynovitis.OrthopClin N Am 2017;48:217-27

Pang HN, Teoh LC, Yam AK, et al. Factors affecting the prognosis of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89:1742.

Draeger RW, Bynum DK Jr. Flexor tendon sheath infections of the hand. J Am AcadOrthopSurg 2012;20:373–82.

Dailiana ZH, Rigopoulos N, Varitimidis S, et al. Purulent flexor tenosynovitis: factors influencing the functional outcome. J Hand SurgEurVol 2008;33:280–5.

Nikkhah D, Rodrigues J, Osman K, Dejager L. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis: one year’s experience at a UK hand unit and a review of the current literature. Hand Surg 2012; 17:199.

Bishop GB, Born T, Kakar S, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of inflammatory blood markers for purulent flexor tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Am 2013;38:2208–11.

Boles SD, Schmidt CC. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.Hand Clin 1998;14:567–78.

Pollen AG. Acute infection of the tendon sheaths. Hand 1974;6:21–5.

Pickens, Anna. "Flexor Tenosynovitis." EM in 5. N.p., 20 Apr. 2014. Web. 10 May 2017.