An engaging and discussion of the severe end of the spectrum of DVT

Hypertensive Emergency

An overview of diagnosis and management of Hypertensive Emergency.

STEMI to OMI: Rethinking who will benefit from PCI

EKG presentations of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction

AIVR in the Emergency Department

An overview of AIVR and its management.

Symptomatic Bradycardia: Considering the Differential Diagnosis

Written by: Keara Kilbane (NUEM ‘25) Edited by: Eric Power (NUEM ‘24)

Expert Commentary by: Seth Trueger, MD, MPH, FACEP

THE HEART CONDUCTION SYSTEM

"Normal” adult heart rates range from 60-100 beats per minute (BPM), with bradycardia defined as a heart rate of less than 60 BPM. Electrical impulses for each heartbeat begin at the sinoatrial (SA) node, then propagate through the atrium to the atrioventricular (AV) node, continuing down the Bundle of His, and lastly to each bundle branch, causing the ventricles to contract. Bradycardia can be physiologic, such as in individuals who have high levels of cardiovascular training. However, pathologic and/or symptomatic bradycardia results from a disruption in this electrical circuit [1].

What is symptomatic bradycardia [1-2]?

Defined as the presence of bradycardia, resulting in debilitating symptoms with lack of alternate explanation.

The most common symptoms include:

Lightheadedness

Syncope

Chest pain

Exercise intolerance

Fatigue

**Important note: The heart rate at which patients experience symptoms may vary based on their ability to increase stroke volume.

CARDIAC OUTPUT = STROKE VOLUME X HEART RATE

Treatment Algorithm for Symptomatic Bradycardia [2-4]:

What are common causes of symptomatic bradycardia [2]?

Myocardial Infarction

Medication

Sinus node dysfunction

Infectious Disease

Hypothermia

Metabolic Abnormalities (hypothyroidism, hyperkalemia, ect.)

Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP)

Genetic Conditions

Myocardial Infarction

Bradyarrhythmias occur in up to 25% of patients with an acute myocardial infarction, especially those involving the right coronary artery (RCA) which supplies the SA node in up to 60% of patients.

Treatment for bradycardia secondary to myocardial infarction is standard care for an occlusive MI, including emergent cardiology consult and cath lab activation, and loading the patient with anti-platelet medications [5-7].

Common Medications and Mechanisms of Causing Bradyarrhythmias

Beta Blockers and Non-Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers (Diltiazem and Verapamil)

Inhibit the automaticity of the SA node

Antiarrhythmics (Amiodarone, Adenosine, Flecainide)

Inhibits the SA and AV node

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (Donepezil, Neostigmine, Pyrodostigmine, Physostigmine)

Activates the parasympathetic nervous system which leads to inhibition of the automaticity of the SA node

Clonidine

Stimulation of central alpha-2-receptors, reducing the norepinephrine

Antidepressants (Citalopram, Escitalopram, Fluoxetine)

Sodium and calcium channel inhibition

Digoxin

Increases vagal tone

Anesthetics (Bupivacaine, Propofol)

Reduces sympathetic activity

Treatment depends on the medication involved. If high suspicion or known overdose, involve and consult your local Poison Center [8].

Sinus Node Dysfunction (Sick Sinus Syndrome) [9-10]:

Sick sinus syndrome is most commonly due to aging of the sinus node and surrounding atrial myocytes. It is often associated with severe bradycardia (HR<50 bpm. It is also associated with sinus pauses, arrests, and SA node block, and or a junctional escape rhythm. Treatment includes permanent pacemaker placement [9].

Hypothermia

Moderate to severe hypothermia can cause significant bradycardia leading to hypotension. Treatment includes removing all wet clothing, externally rewarming with bair huggers and warm blankets, administering warm IV fluids, active core rewarming including bladder and thoracic irrigation with warmed fluids). It is also important to remember that the differential to hypothermia itself is broad itself and not just limited to environmental exposure. For example, hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, sepsis, neuromuscular disease, malnutrition, thiamine deficiency, hypoglycemia can all lead to hypothermia [11-13].

Decompensated Hypothyroidism (Myxedema Coma)

Classic symptoms of myxedema coma include:

Decreased mentation or delirium

Hypothermia

Bradycardia

Hyponatremia

Hypoglycemia

Hypoventilation

Hypotension

Common triggering events:

Infection

Medication non-adherence

Surgery or trauma

Myocardial infarction

CHF exacerbation

Cerebral Vascular Accident

GI bleed

Treatment includes IV atropine if unstable while treating the underlying condition (IV steroids, IV levothyroxine) [14].

Increased Intracranial Pressure

Classic triad of bradycardia, respiratory depression, and hypertension (Cushing reflex), concerning for brainstem compression and/or herniation [15].

Treatment includes treating the underlying condition, and stabilization through maneuvers including [15]:

Hyperventilation

Head of the bed elevation to maximize venous outflow

Ensure neck braces (c-collar) is appropriately placed (not too tight)

Hypertonic solutions like mannitol or hypertonic saline

Emergent craniotomy

Other Etiologies of Symptomatic Bradycardia [15-16]

Prolonged hypoxia

Severe electrolyte derangements (hyperkalemia)

Vagal response

Severe obstructive sleep apnea

Genetic channelopathies

References:

Spodick, D. H., Raju, P., Bishop, R. L., & Rifkin, R. D. (1992). Operational definition of normal sinus heart rate. The American Journal of Cardiology, 69(14), 1245–1246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(92)90947-w

UpToDate. (n.d.). Www.uptodate.com. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sinus-bradycardia?search=Bradycardia&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&disp

Spodick, D. H. (1992). Normal sinus heart rate: Sinus tachycardia and sinus bradycardia redefined. American Heart Journal, 124(4), 1119–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8703(92)91012-p

ACLS Bradycardia Algorithm. (n.d.). ACLS Medical Training. https://www.aclsmedicaltraining.com/adult-bradycardia-algorithm/

A. A. J. Adgey, Geddes, J. S., Mulholland, H., Keegan, D., & Pantridge, J. F. (1968). INCIDENCE, SIGNIFICANCE, AND MANAGEMENT OF EARLY BRADYARRHYTHMIA COMPLICATING ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION. The Lancet, 292(7578), 1097–1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91577-8

UpToDate. (n.d.). Www.uptodate.com. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sinus-node-dysfunction-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-and-evaluation?search=bradycardia&source=

ROTMAN, M., WAGNER, G. S., & WALLACE, A. G. (1972). Bradyarrhythmias in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation, 45(3), 703–722. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.45.3.703

Tisdale, J. E., Chung, M. K., Campbell, K. B., Hammadah, M., Joglar, J. A., Leclerc, J., & Rajagopalan, B. (2020). Drug-Induced arrhythmias: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation, 142(15). https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000905

Kusumoto, F. M., Schoenfeld, M. H., Barrett, C., Edgerton, J. R., Ellenbogen, K. A., Gold, M. R., Goldschlager, N. F., Hamilton, R. M., Joglar, J. A., Kim, R. J., Lee, R., Marine, J. E., McLeod, C. J., Oken, K. R., Patton, K. K., Pellegrini, C. N., Selzman, K. A., Thompson, A., & Varosy, P. D. (2019). 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and

Cardiac Conduction Delay. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 74(7), e51–e156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.044

Farkas, J. (2021, October 1). Hypothermia. EMCrit Project. https://emcrit.org/ibcc/hypothermia/

UpToDate. (n.d.). Www.uptodate.com. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/accidental-hypothermia-in-adults?search=hypothermia&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_r

Näyhä, S. (2005). Environmental temperature and mortality. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 64(5), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v64i5.18026

Decompensated Hypothyroidism (“Myxedema Coma”). (n.d.). EMCrit Project. https://emcrit.org/ibcc/myxedema/#treatment_of_cause

UpToDate. (n.d.). Www.uptodate.com. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-and-management-of-elevated-intracranial-pressure-in-adults?search=increased%20intracranial%20pressure&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150&usage

UpToDate. (n.d.). Www.uptodate.com. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sinus-bradycardia?search=Bradycardia&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=

Expert Commentary

Thank you for this nice review of the differential diagnosis of bradycardia. As emergency physicians, it’s easy to slip into the default of “symptomatic/unstable” vs “asymptomatic/stable” and slip past the underlying causes, and with bradycardia (as with many things), patients are often not divided quite so neatly.

Similarly, the context matters considerably: what resources are available? Is a cardiologist who can place a permanent pacer upstairs and ready with a staffed lab? Or is “definitive care” hours away (eg, requires transfer, or the cardiology team needs to come in from home). A patient with bradycardia from an acute MI will need the cath lab regardless, but in settings that require a transfer that may require transvenous pacemaker prior to transfer. On the other hand, a patient being whisked upstairs to a cath lab requires a different conversation with the cardiology team, eg preparing for transcutaneous pacing while getting the patient from the door to the balloon in a handful of minutes.

The differential can also be helpful when considering other logistics. For example, while I am happy to place a transvenous pacemaker for a patient who needs it for, say, a high degree AV block from Lyme disease, I may consider if the patient is stable enough to have a transvenous pacer placed more elegantly by the cardiology team as the patient may keep the TVP for 2 weeks but not need a permanent pacemaker.

Of course there are also secondary causes of bradycardia that need other, non-cardiac, definitive treatments, eg, overdose, hypothermia, Cushing’s response, and of course, hyperkalemia; keeping the differential in mind is part of the reason why we have not yet been replaced by robots.

Seth Trueger, MD, MPH, FACEP

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Kilbane, K. Power, E. (2024, Jun 17). Symptomatic Bradycardia: Considering the Differential Diagnosis. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Trueger, S]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/symptomatic-bradycardia

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Review of the ATHOS 3 trial

Written by: Saabir Kaskar, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Amanda Randolph, MD (NUEM ‘20)

Expert Commentary by: Matt McCauley, MD (NUEM’ 21)

Review of the ATHOS 3 Trial: Angiotensin II for the Treatment of Vasodilatory Shock

Angiotensin, first isolated in the late 1930s, in recent years has become the new innovative vasopressor used in intensive care units, a change driven largely by the results of the ATHOS-3 trial. The ATHOS-3 trial in 2017 explored the efficacy of angiotensin II as a vasopressor for severe vasodilatory shock. Severe shock is defined as persistent hypotension requiring vasopressors to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65mmHg and serum lactate <2 despite adequate volume resuscitation. Two classes of vasopressors have been used in the past for hypotension. They are catecholamines and vasopressin-like peptides. The human body, however, employs a third class which is angiotensin. Angiotensin II is an octapeptide hormone and a potent vasopressor that is an integral component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. It works by activating the ANGII type 1 receptor which subsequently activates a G coupled protein pathway and phospholipase C, thereby inducing vasoconstriction.

The ATHOS-3 trial compared the efficacy and safety of angiotensin II versus placebo in catecholamine-resistant hypotension, which is defined as an inadequate response to standard doses of vasopressors. The study was designed as a phase III multicenter randomized placebo control trial taking place across 75 intensive care units in the United States from 2015 to 2017. The three main inclusion criteria were catecholamine-resistant hypotension (defined as >0.2ug/kg/min of norepinephrine or equivalent for 6-48 hours to maintain a MAP 55-70 mmHg), adequate volume resuscitation (25mL/kg of crystalloid), and features of vasodilatory shock (mixed venous O2 >70% and CVP >8mmHg or cardiac index >2.3 L/min/m2).

Patients in vasodilatory shock that met the criteria of catecholamine-resistant hypotension were randomized to treatment with angiotensin II or placebo. Angiotensin II was initiated at an infusion rate of 20ng/kg/min and adjusted during the first three hours to increase MAP to at least 75mmHg. The primary outcome of the study was the response in MAP three hours after the start of angiotensin II infusion. A response was deemed as a MAP increase of 10mmHg from baseline or a MAP over 75mmHg without an increase in baseline vasopressor infusions. During the first three hours, the angiotensin II group had a significantly greater increase in MAP than placebo (12.5mmHg vs 2.9 mmHg). Angiotensin II also allowed for rapid increases in MAP which permitted decreases in doses of baseline catecholamine vasopressor. Additionally, improvement in the cardiovascular SOFA score was significantly greater in the angiotensin II group than in the placebo group. However, the overall SOFA score did not differ between groups. Rates of adverse events such as tachyarrhythmias, distal ischemia, ventricular tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation were similar in the angiotensin II and placebo groups. Overall serious adverse events that included infectious, cardiac, respiratory, gastrointestinal, or neurologic events were reported in 60.7% of patients who received angiotensin II and 67.1% of patients who received placebo.

The strengths and limitations of the ATHOS 3 trial are critical to how its author’s conclusions should be interpreted. The strengths of the study include that it was a randomized double-blind control trial examining a new class of vasopressor for refractory vasodilatory shock. Refractory shock is a common condition with high mortality, and so the investigation of an additional treatment modality can be of great clinical impact. However, one limitation of the study was that it was underpowered to demonstrate a mortality difference. It showed improvement in blood pressure which is a clinically important parameter but not a patient-oriented outcome. Interestingly, when vasopressin was studied in 2008, it similarly did not show a mortality benefit when added to norepinephrine infusion in septic shock2. It did, however, show a decrease in norepinephrine dosing which parallels the findings of the ATHOS 3 trial.

An additional point of contention with the ATHOS 3 trial is that the manuscript does not report an increase in thrombotic risk. It has been shown that angiotensin II increases thrombin formation and impairs thrombolysis3. The FDA even reports angiotensin II has a risk for thrombosis as there was a higher incidence (13% vs 5%) of arterial and venous thrombotic events in the angiotensin II vs placebo group in the ATHOS 3 trial itself. For this reason, the FDA recommends concurrent VTE prophylaxis with the use of angiotensin II. Further data regarding the thrombotic risk of angiotensin II would be helpful to determine which patient populations the vasopressor should be avoided in.

Overall, the author’s conclusion in the ATHOS 3 trial is that angiotensin II increased blood pressure in patients with a vasodilatory shock that did not respond to high doses of conventional vasopressors. It has been shown to raise mean arterial pressure over 75 mm Hg or by an increase of 10 mm Hg within three hours. The ATHOS 3 trial, however, did not demonstrate a mortality benefit when using angiotensin II. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether Angiotensin II truly improves patient outcomes in vasodilatory shock.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for this great summary of the ATHOS 3 trial. While this trial paved the way for the clinical use of angiotensin II as a vasopressor, you’ve raised some salient points as to why we should approach this emerging intervention with skepticism. The biggest shortcoming in my mind is the primary outcome of the study; it’s not particularly impressive that a vasopressor resulted in higher blood pressures compared to a placebo. Mortality benefit is an extremely elusive goal in critical care research1 but that doesn’t discount the fact that ATHOS 3 wasn’t designed to demonstrate an improvement in any patient-oriented outcome. ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, ventilator-dependent days, or rate of renal replacement therapy: these are all things that matter to our patients and to our health systems and they are more fruitful targets when we investigate interventions.

There’s been some study of angiotensin II in the years since it has landed in our hospital formularies and there has not been robust data supporting its use. Some of the most recent data come from a multi-center retrospective study that includes patients from Northwestern. This review of 270 patients receiving angiotensin II demonstrated that 67% of patients were able to maintain a MAP of 65 with stable or reduced vasopressor doses. Univariate analysis showed that these patients that responded did have a statistically significant mortality benefit over the patients deemed nonresponders (41% vs 25%)2. If we are going to find a benefit of this drug, further study predicting which patients will be responders is necessary but this study did note that patients already receiving vasopressin and those with lower lactates (6.5 vs 9.5) were more likely to respond. Outside of septic shock, there is interest in the use of angiotensin II in refractory vasoplegia associated with post-cardiac surgery3 and anti-hypertensive overdose4. These are, of course, only hypothesis-generating.

But what does that mean to us clinically in the ED and ICU? This data shows us that angiotensin II can make the blood pressure better but I would never let it distract you from the things we know matter in sepsis resuscitation. Source control timely antibiotics, rational fluid resuscitation, and ruling out other causes of vasopressor refractory shock to include anaphylaxis, hemorrhage, adrenal insufficiency, LVOT obstruction, and any other cause of cardiogenic shock need to be ruled out and addressed. In my personal practice, I make sure to optimize these and start vasopressin shortly after the initiation of norepinephrine. In a patient already on vaso that has stopped responding to escalating doses of norepinephrine, I reach for my ultrasound probe and reassure myself that there isn’t significant sepsis-related myocardial dysfunction because those patients may benefit from a trial of an inotrope like epinephrine. In those with a good cardiac squeeze, I think it’s appropriate to discuss with your intensivist and clinical pharmacist the utility of adding angiotensin II as part of a kitchen-sink approach. Until we have more data about the benefits of this extremely expensive intervention, I wouldn’t lose sleep if you’re unable to secure it for your patient.

References

Chawla LS et al. Intravenous Angiotensin II for the Treatment of High-Output Shock (ATHOS Trial): A Pilot Study. Crit Care 2014; 18(5): 534. PMID: 25286986

Russell JA et al. Vasopressin Versus Norepinephrine Infusion in Patients with Septic Shock. NEJM 2008; 358(9): 877 – 87. PMID: 18305265

Celi A et al. Angiotensin II, Tissue Factor and the Thrombotic Paradox of Hypertension. Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy 2010; 8(12): 1723-9 PMID: 21108554

Santacruz CA, Pereira AJ, Celis E, Vincent JL. Which Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trials in Critical Care Medicine Have Shown Reduced Mortality? A Systematic Review. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(12):1680-1691. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004000

Wieruszewski PM, Wittwer ED, Kashani KB, et al. Angiotensin II Infusion for Shock: A Multicenter Study of Postmarketing Use. Chest. 2021;159(2):596-605. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2074

Papazisi O, Palmen M, Danser AHJ. The Use of Angiotensin II for the Treatment of Post-cardiopulmonary Bypass Vasoplegia. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. Published online October 21, 2020. doi:10.1007/s10557-020-07098-3

Carpenter JE, Murray BP, Saghafi R, et al. Successful Treatment of Antihypertensive Overdose Using Intravenous Angiotensin II. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(3):339-344. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.05.027

Matt McCauley, MD

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Kaskar, S. Randolph, A. (2022, Feb 14). Review of ATHOS 3 trial. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by McCauley, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/review-athos3-trial.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection

Written by: John Li, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Andra Farcas, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Aortic ultrasound is a staple in emergency point of care ultrasound. It has incredible sensitivity (97.5-100%) and specificity (94.1-100%) in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysms and can provide a diagnosis for critically ill patients in seconds. [1-4] However, it can often be a technically difficult study for beginner sonographers due to shadowing bowel gas and patient body habitus. Follow along in this installment of our Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series to become an expert in finding aortas!

Beyond the classic elderly male smoker with abdominal, flank, or back pain, what are other scenarios where you would use aortic ultrasound?

Older patients with limb ischemia - an aortic aneurysm can have atherosclerosis or a mural thrombus which can embolize and cause an arterial occlusion!

“But they fixed my aorta!” Aortic endograft leakage can sometimes present with symptoms that are similar to a AAA rupture, such as back pain, flank pain, or hemodynamic instability.

How to scan like a Pro

Always Start Smart: Aortic ultrasound can be tricky because of factors that seem out of our control, such as bowel gas or patient body habitus.

When scanning for an abdominal aortic aneurysm, start scanning in the epigastric region with a transverse view and apply constant pressure, gently pushing the bowel gas out of the way as you slide the probe down towards the patient’s feet.

Tell your patients to bend their knees! This relaxes the abdominal musculature and can help you move bowel gas or make better contact with the probe.

What if you still can’t see it? Try looking in the right upper quadrant view of the FAST exam!

Start with your probe in the right mix-axillary line and use the liver as your acoustic window. You may need to fan anteriorly or posteriorly depending on the patient’s body habitus and your positioning.

Unfortunately, this view predominantly visualizes the superior aspect of the abdominal aorta, and it can be difficult to visualize the inferior abdominal aorta or the bifurcation.

Here we are looking at a modified RUQ view, where the aorta is visualized on the bottom part of the screen using the liver as an acoustic window. (acep.org)

Pro Pickups!

What’s that weird aneurysm?

Most people are familiar with the classic fusiform aortic aneurysm, but saccular aneurysms can be easily missed because of shadowing bowel gas obstructing parts of the aorta. Saccular aneurysms actually have a higher risk of rupture and repair is recommended for smaller diameters.

Here you can see two images in the longitudinal axis of the different kinds of abdominal aortic aneurysms. On the left is a saccular aneurysm and on the right is a fusiform one. Be sure to pay attention to the mural thrombus in the walls of both of these aortas - they can embolize and cause arterial occlusions! (med.emory.edu)

2. How big is that aorta anyways?

Be sure to always measure the aorta from outside wall to outside wall!

Many aortic aneurysms have a mural thrombus or intraluminal clot, and it can be very easy to mistake these for extra-luminal contents.

Remember the concerning numbers: >5.5cm for men and >5cm for women!

What the Pros Do Next

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

If the patient is hemodynamically unstable (defined as BP <90/60, altered mental status, or other signs of end-organ damage), go straight to the OR!

If the patient is hemodynamically stable (defined as the absence of any of the above), then the next step is to obtain further imaging, such as a CT Angiogram, which is the imaging gold standard.

If you are concerned about a large AAA that could be a contained leak but the patient is hemodynamically stable, then we recommend an emergent vascular surgery consult

If you find a small AAA (defined as <5cm in women or <5.5cm in men) that you do not think is actively contributing to the patient’s symptoms, then we recommend outpatient vascular surgery follow up

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

Do you want to review more examples of pathologic images that you may see when you are doing an aortic ultrasound? Be sure to check out The Pocus Atlas by our expert editor Dr. Macias. Aortic pathology is quite rare, and going through these images will help immensely in recognizing this diagnosis in emergent situations. If you’re interested in looking at some of the evidence behind aortic ultrasound, be sure to check out the evidence atlas here as well.

References

Rubano E, Mehta N, Caputo W, Paladino L, Sinert R. Systematic review: emergency department bedside ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Feb;20(2):128-38. doi: 10.1111/acem.12080. PMID: 23406071.

Hunter-Behrend, Michelle, and Laleh Gharahbaghian. “American College of Emergency Physicians.” ACEP // Home Page, 2016, www.acep.org/how-we-serve/sections/emergency-ultrasound/news/february-2016/tips-and-tricks-big-red---the-aorta-and-how-to-improve-your-image/.

Ma, John, et al. Ma and Mateer's Emergency Ultrasound. McGraw-Hill Education, 2020.

Mallin, Mike, and Matthew Dawson. Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound: Volume 1. Emergency Ultrasound Solutions, 2013.

Macias, Michael. TPA, www.thepocusatlas.com/.

Expert Commentary

Another great Sono Pro Post! Thank you John Li and Andra for helping everyone move from good to great when scanning for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. As noted, this application defines Emergency Ultrasound as a fast (pun intended), accurate, and life saving diagnostic tool for every EM physicians tool belt. When consistent probe pressure does not do the trick, consider the RUQ view for a quick look. Since most AAA’s are fusiform, this may quickly confirm your suspicions and prompt the call to get the OR ready. Be sure to visualize the entire abdominal aorta throughout in both short and long axis to identify saccular aneurysms and even the rare aortic occlusion!

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Li, J. Farcas, A. (2021 Oct 11). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Aortic Aneurysm. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-aortic-aneurysm

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pulmonary Embolism

Written by: Megan Chenworth, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Abiye Ibiebele, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did you know that focused transthoracic cardiac ultrasound (FOCUS) can help identify PE in tachycardic or hypotensive patients? (It has been shown to have a sensitivity of 92% for PE in patients with an HR>100 or SBP<90, and approaches 100% sensitivity in patients with an HR>110 [1]). Have a hemodynamically stable patient with PE and wondering how to risk stratify? FOCUS can identify right heart strain better than biomarkers or CT [2].

Who to FOCUS on?

Patients presenting with chest pain or dyspnea without a clear explanation, or with a clinical concern for PE. The classic scenario is a patient with pleuritic chest pain with VTE risk factors such as recent travel or surgery, systemic hormones, unilateral leg swelling, personal or family history of blood clots, or known hypercoagulable state (cancer, pregnancy, rheumatologic conditions).

Patients presenting with unexplained tachycardia or dyspnea with VTE risk factors

Unstable patients with undifferentiated shock

When PE is suspected but CT is not feasible: such as when the patient is too hemodynamically unstable to be moved to the scanner, too morbidly obese to fit on the scanner, or in resource-limited settings where scanners aren’t available

One may argue AKI would be another example of when CT is not feasible (though there is some debate over the risk of true contrast nephropathy - that is a discussion for another blog post!)

How to scan like a Pro

Key is to have the patient as supine as possible - this may be difficult in truly dyspneic patients

If difficulty obtaining views arise, the left lateral decubitus position helps bring the heart closer to the chest wall

FOCUS on these findings

You only need one to indicate the presence of right heart strain (RHS).

Right ventricular dilation

Septal flattening: Highly specific for PE (93%) in patients with tachycardia (HR>100) or hypotension (SBP<90) [1]

Tricuspid valve regurgitation

McConnell’s sign

Definition: Akinesis of mid free wall and hypercontractility of apical wall (example below)

The most specific component of FOCUS: 99% specific for patients with HR>100bpm or SBP<90 [1]

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE)

The most sensitive single component of FOCUS: TASPE < 2cm is 88% sensitive for PE in tachycardic and hypotensive patients; 93% sensitive when HR > 110 [1]

Where to FOCUS

Apical 4 Chamber (A4C) view: your best shot at seeing it all

Find the A4C view in the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line

Optimize your image by sliding up or down rib spaces, sliding more lateral towards the anterior axillary line until you see the apex with the classic 4 chambers - if the TV and MV are out of the plane, rotate the probe until you can see both openings in the same image; if the apex is not in the middle of the screen, slide the probe until the apex is in the middle of the screen. If you are having difficulty with this view, position the patient in the left lateral decubitus.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the normal RV: LV ratio in diastole is 0.6:1. If the RV > LV, it is abnormal. (see in the image below)

Septal flattening/bowing is best seen in this view

McConnell’s sign: akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

McConnell’s Sign showing akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

4. Tricuspid regurgitation can be seen with color flow doppler when positioned over the tricuspid valve

Tricuspid regurgitation seen with color doppler flow

5. TAPSE

Only quantitative measurement in FOCUS, making it the least user-dependent measurement of right heart strain [3]

A quantitative measure of how well the RV is squeezing. RV squeeze normally causes the tricuspid annulus to move towards the apex.

Fan to bring the RV as close to the center of the screen as possible

Using M-mode, position the cursor over the lateral tricuspid annulus (as below)

Activate M-mode, obtaining an image as below

Measure from peak to trough of the tracing of the lateral tricuspid annulus

Normal >2cm

How to measure TAPSE using ultrasound

Parasternal long axis (PSLA) view - a good second option if you can’t get A4C

Find the PSLA view in the 4th intercostal space along the sternal border

Optimize your image by sliding up, down, or move laterally through a rib space, by rocking your probe towards or away from the sternum, and by rotating your probe to get all aspects of the anatomy in the plane. The aortic valve and mitral valve should be in plane with each other.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the RV should be roughly the same size as the aorta and LA in this view with a 1:1:1 ratio. If RV>Ao/LA, this indicates RHS.

Septal flattening/bowing of the septum into the LV (though more likely seen in PSSA or A4C views)

Right heart strain demonstrated by right ventricle dilation

Parasternal Short Axis (PSSA) view: the second half of PSLA

Starting in the PSLA view, rotate your probe clockwise by 90 degrees to get PSSA

Optimize your image by fanning through the heart to find the papillary muscles - both papillary muscles should be in-plane - if they are not, rotate your probe to bring them both into view at the same time

Important findings:

Septal flattening/bowing: in PSSA, it is called the “D-sign”.

“D-sign” seen on parasternal short axis view. The LV looks like a “D” in this view, particularly in diastole.

Subxiphoid view: can add extra info to the FOCUS

Start just below the xiphoid process, pointing the probe up and towards the patient’s left shoulder

Optimize your image by sliding towards the patient’s right, using the liver as an echogenic window; rotate your probe so both MV and TV are in view in the same image

Important findings

Can see plethoric IVC if you fan down to IVC from RA (not part of FOCUS; it is sensitive but not specific to PE)

Plethoric IVC that is sensitive to PE

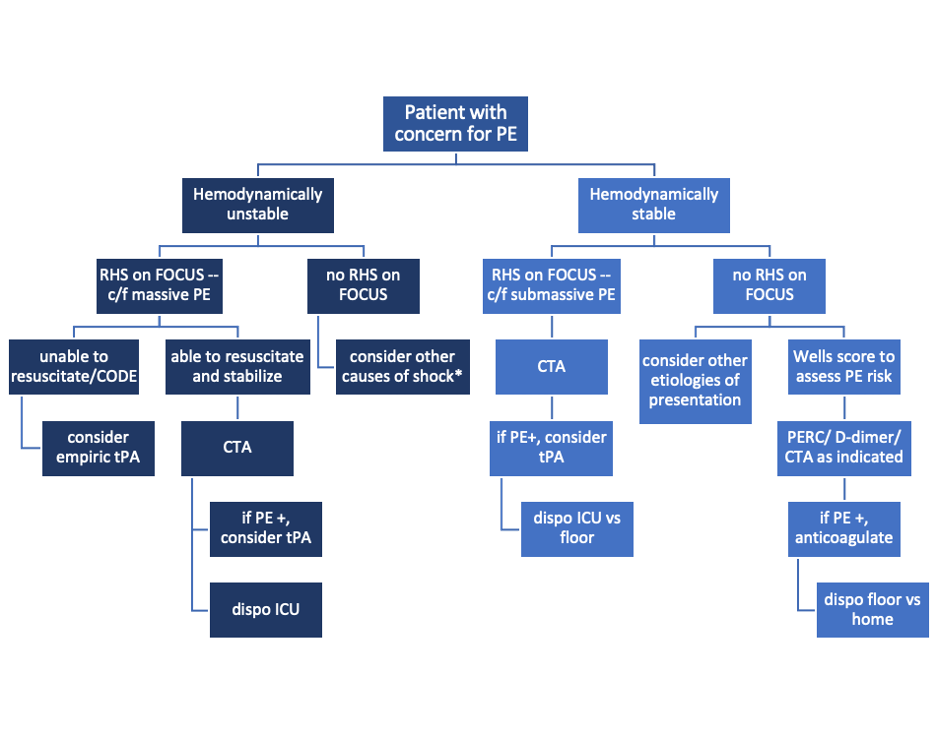

What to do next?

Sample algorithm for using FOCUS to assess patients with possible PE.

*cannot completely rule out PE, but negative FOCUS makes PE less likely

Limitations to keep in mind:

FOCUS is great at finding heart strain, but the lack of right heart strain does not rule out a pulmonary embolism

Systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the overall sensitivity of FOCUS for PE is 53% (95% CI 45-61%) for all-comers [5]

Total FOCUS exam requires adequate PSLA, PSSA, and A4C views – be careful when interpreting inadequate scans

Can see similar findings in chronic RHS (pHTN, RHF)

Global thickening of RV (>5mm) can help distinguish chronic from acute RHS

McConell’’s sign is also highly specific for acute RHS, whereas chronic RV failure typically appears globally akinetic/hypokinetic

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

Right Heart Strain at 5-Minute Sono: http://5minsono.com/rhs/

Ultrasound GEL for Sono Evidence: https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/EJHu_SYvE4oBT4igNHGBrg, https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/OOWIk1H2dePzf_behpaf-Q

The Pocus Atlas for real examples: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/echocardiography-2

The Evidence Atlas for Sono Evidence: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/ea-echo

References

Daley JI, Dwyer KH, Grunwald Z, Shaw DL, Stone MB, Schick A, Vrablik M, Kennedy Hall M, Hall J, Liteplo AS, Haney RM, Hun N, Liu R, Moore CL. Increased Sensitivity of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound for Pulmonary Embolism in Emergency Department Patients With Abnormal Vital Signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Nov;26(11):1211-1220. doi: 10.1111/acem.13774. Epub 2019 Sep 27. PMID: 31562679.

Weekes AJ, Thacker G, Troha D, Johnson AK, Chanler-Berat J, Norton HJ, Runyon M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Right Ventricular Dysfunction Markers in Normotensive Emergency Department Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Sep;68(3):277-91. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.027. Epub 2016 Mar 11. PMID: 26973178.

Kopecna D, Briongos S, Castillo H, Moreno C, Recio M, Navas P, Lobo JL, Alonso-Gomez A, Obieta-Fresnedo I, Fernández-Golfin C, Zamorano JL, Jiménez D; PROTECT investigators. Interobserver reliability of echocardiography for prognostication of normotensive patients with pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014 Aug 4;12:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-29. PMID: 25092465; PMCID: PMC4126908.

Hugues T, Gibelin PP. Assessment of right ventricular function using echocardiographic speckle tracking of the tricuspid annular motion: comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance. Echocardiography. 2012 Mar;29(3):375; author reply 376. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01625_1.x. PMID: 22432648.

Fields JM, Davis J, Girson L, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:714–23.e4.

Expert Commentary

RV function is a frequently overlooked area on POCUS. Excellent post by Megan looking specifically at RV to identify hemodynamically significant PEs. We typically center our image around the LV, so pay particular attention to adjust your views so the RV is optimized. This may mean moving the footprint more laterally and angle more to the patient’s right on the A4C view. RV: LV ratio is often the first thing you will notice. When looking for a D-ring sign, make sure your PSSA is actually in the true short axis, as a diagonal cross-section may give you a false D-ring sign. TAPSE is a great surrogate for RV systolic function as RV contracts longitudinally. Many patients with pulmonary HTN or advanced chronic lung disease can have chronic RV failure, lack of global RV thickening. Lastly remember, that a positive McConnell’s sign is a great way to distinguish acute RHS from chronic RV failure.

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Chenworth, M. Ibiebele, A. (2021 Oct 4). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pulmonary Embolism. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-pulmonary-embolism

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Cocaine Chest Pain

Written by: Maren Leibowitz, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Zach Schmitz, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: David Farman, MD

Expert Commentary

Cocaine chest pain was something that was frequently discussed but rarely encountered during my training and during my 11 years practicing in suburban and metropolitan Indiana (we're more of a heroin/meth state). I suspect there is significant regional and local variation in the epidemiology of cocaine chest pain, likely influenced by the economics and local availability or popularity of intoxicants.

When cocaine is more expensive, we tend to see more methamphetamine use. And vice-versa. I was once told by a local sheriff that "people will get high on whatever they can get for less than $20" and I have found that to be true in practice. I wouldn't expect that an emergency physician would be intimately familiar with the local micro-economics of the drug trade, but one should expect there to be a periodic waxing/waning of cocaine chest pain presentations. Similarly, it may be a more frequent complaint dependent on cocaine's local popularity and availability.

When consulting with a Cardiologist about a cocaine chest pain case, it is important for the emergency physician to avoid letting premature closure or psychosocial biases unduly influence the patient's disposition. It is not unheard of for physicians to minimize objective findings (ST segment abnormalities or biomarker elevation) and attribute them to the vasoactive properties of cocaine. I have certainly been tempted to do so myself. However, the article wisely points out the physiologic changes induced by cocaine use, both acutely and chronically. Platelet aggregation and atherogenesis can absolutely promote a scenario that would require PCI in even the most frequent of 'frequent fliers' with cocaine chest pain.

In short, I would have a low threshold to involve Cardiology in a patient who has objective findings regardless of their use of cocaine. Similarly, a Cardiology request for a Urine Drug Screen shouldn't delay a patient's trip to the cath lab if they have a STEMI. An exception to this may be a patient who has had recent coronary angiography that objectively demonstrates normal coronaries. In that scenario I would consider serial markers, conservative management and strong consideration of non-cardiac causes of the pain (dissection, pneumothorax, etc.).

David Farman, MD FACEP

Emergency Medicine Physician

Franciscan Health Lafayette East

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Leibowitz, M. Schmitz, Z. (2021, May 10). Cocaine Chest Paine. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Farman, D]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/cocaine-chest-pain

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Apple Heart Study

Written by: Em Wessling, MD (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Dana Loke, MD (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Rod Passman, MD

Chief Complaint: My watch thinks I have Atrial Fibrillation!

As technology advances, medicine must continue to advance in pace. Wearable technology has been evolving for decades. The information gathered from a wide range of these devices may someday help to provide healthcare workers with valuable information about a patient’s condition. However, for now, there is limited research on their utility within the healthcare field.

Thus far, both Apple Watch and Fitbit have been shown to correctly identify tachycardia during atrial tachyarrhythmias, but their accuracy to the heart rate varied with the type of arrhythmia (1,2). Apple Watch has been shown to be more accurate than Fitbit (1,2). The WATCH AF trial demonstrated it was possible with reasonable sensitivity (93.7%) and specificity (98.2) to use smart watches to diagnose Atrial Fibrillation (3).

How Apple Watch is tracking atrial fibrillation:

- Photoplethysmography: the use of light to determine volume within a structure at a given time

- Pulse is estimated by time between peak volume seen by photoplethysmography.

- When the pulse is highly variable between consecutive beats, irregular heart beat is suspected.

Apple Heart Study: The plan and the preliminary data (4, 5)

Study Design: Prospective, single arm pragmatic study

- Enrolled 419,093 participant

- Inclusion Criteria: appropriate Apple technology, Age≥22 years, US resident, proficient in English, valid phone number and email.

- Exclusion criteria: self-reported atrial fibrillation , atrial flutter, or anticoagulation

- Methods: “Irregular Pulse Notification” (indication of possible atrial fibrillation) sent to participants if 5/6 irregular pulses within 48 hour period, at which point participant was instructed to wear EKG patch for up to 7 days.

- Primary Outcome: Proportion of patients alerted with “Irregular Pulse Notification” who were found to have atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter on EKG patch, in the 65+ population as well as in all-comers.

- Secondary Outcomes: Positive predictive value (PPV) of irregular heart rhythm notification; percentage of those with irregular notification who contacted a health care professional within 3 months.

Preliminary Data presented at ACC:

- Participants who received “Irregular Pulse Notification”: 2,161 (0.52% all comers)

- Participants age >65 who received “Irregular Pulse Notification”: >3%

- EKG Patches sent to 658 participants; 450 returned.

34% of those returned showed atrial fibrillation

PPV for Tachogram: 71%

PPV for “Irregular Pulse Notification”: 84%

- Notification to doctor - approx. 50%

Limitations:

Small sample size for EKG patches, despite high enrollment

Self-reported data

Self-selecting group, i.e.may not be able to extrapolate prevalence data to those who do not wear smart watches

Potential Impact on Emergency Departments:

As more and more studies validate the accuracy of wearable technology to measure and recognize health conditions, the implications must be analyzed as well.

Prior to 2017, researchers began to predict that there would be an expansive increase in the rates of atrial fibrillation due to “worldwide aging” (6). While this review acknowledged there were “potential applications” for smart phone technology in the diagnosis, their predictions of the expanse of the epidemic of atrial fibrillation preceded definitive research showing increased diagnosis rates with wearable technology, which will likely only further expedite this growing patient population. The mSToPS Trial showed that immediate in-home monitoring with an EKG patch had 3% greater rates of atrial fibrillation diagnosis compared to delayed EKG monitoring at 4 months. This led to increased use of anticoagulants and increased health care utilization (7). If this increase was seen with EKG patches, consider the influx of patients to primary care and cardiology clinics in addition to emergency departments that can be projected based on the rise of smart watch detection of atrial fibrillation. Researchers in Australia had begun studying this prior to the commencement of the Apple Heart Study (8). When cardiac patients were asked if they trusted smart watches to predict arrhythmia and measure their heart rate only 53% agreed; however, that did not stop 91% from reporting they would seek care if their watch alerted them about an abnormality (8). While the preliminary data from the Apple Heart study shows that a much smaller percentage of those who were not previously cardiac patients sought medical care when alerted by their Apple Watch, further study is needed to see the extent to which advances in smart watch health technology will lead to an influx in patients to the Emergency Department due to concerns of arrhythmia found by a smartwatch (5).

While the accuracy of these methods of arrhythmia detection are still being studied, the potential for ED presentation with this chief complaint will continue to rise. In the fourth quarter of 2017 financial year, Apple alone sold greater than 8 million smart watches worldwide, making it the largest watch vender in the world (9). With these increased sales, comes the potential for increased recognition of arrythmia by smartwatch. Healthcare organizations throughout the country must strive to develop effective and efficient clinical pathways in order to evaluate, potentially diagnose, and treat this patient population. Upon presentation to the Emergency Department, each patient should receive an EKG, telemetry monitoring while in the Emergency Department and screaming lab work: often including CBC, BMP + Mg, and troponin. From there, the pathway may vary. Many would agree, if the patient is and has always been asymptomatic, work up is unremarkable, with normal sinus rhythm on their EKG, discharge home with an EKG patch and follow up with cardiology is reasonable. Conversely, an EKG showing atrial fibrillation would constitute a new diagnosis and further work up would proceed as with any other new diagnosis of Atrial Fibrillation. However, for those who fall in-between, the disposition is not as clear. What would you do?

Expert Commentary

More than 800 years ago, Maimonides described an irregular pulse that likely represented atrial fibrillation (AF). The development of the electrocardiogram by Einthoven 700 years later allowed surface recordings of human AF for the first time.1 With the recognition that AF is often asymptomatic and paroxysmal, the development of inexpensive, non-invasive, passive monitors for irregular rhythm identification has long been recognized as a potentially important tool for arrhythmia detection and management.

At its core (pun intended), the purpose of the Apple Heart Study was to assess the feasibility of AF screening in large populations by monitoring participants with a wrist-worn photoplethysmography (PPG) monitor.2 The PPG algorithm in the Apple Watch samples the pulse several times daily during periods of physical inactivity and increases the sampling rate if an irregular tachogram is detected. If 5 out of 6 tachograms are consistent with AF (requiring > 60 minutes of AF), the wearer receives an irregular rhythm notification. Since the version of the Apple Watch used in the study did not have the 30-second ECG feature (available in Series 4 watches and later), the Apple Heart Study protocol asked those who received the irregular rhythm notification to wear an ECG patch at a later date.

Several important facts can be gleaned from the Apple Heart Study. First, the study virtually enrolled 419,297 individuals in less than a year, a testament to the interest in the subject matter, the ease of remote enrollment when appropriate, and the enormous potential of digital health studies. Second, the fear that the healthcare system would be inundated with false positive AF notifications appears unfounded as 99.8% of participants under age 40 did not receive an irregular rhythm notification. Third, the positive predictive value for the irregular rhythm notification was surprisingly high (84%) despite that fact that the patch was applied a mean of 13 days following the notification and was worn for less than 7 days on average. This last point is worth emphasizing since with paroxysmal AF, a negative monitor placed two weeks after an irregular rhythm notification may simply mean that AF was not present during both time periods.

The study also has some important caveats. The Apple Heart Study did not report the sensitivity and specificity of the PPG algorithm for AF detection, a critical piece of missing data needed for clinical care and future research. Furthermore, only a minority of patients who received an irregular rhythm notification actually wore and returned the ECG monitor, showing that virtual enrollment doesn’t always translate into virtual protocol compliance. From a research perspective, wearable AF monitors have allowed for large-scale screening studies such as the Huawei Heart and Heartline Studies aimed at understanding the true prevalence of AF and the risks and benefits of early detection and treatment.3,4 From a clinical perspective, a patient who says “my watch says I have AF” still requires ECG confirmation, but that too has been made easier with the new generation of wearables.

References

1. Prystowsky EN. The history of atrial fibrillation: the last 100 years. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(6):575-582. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01184.

2. Perez MV, Mahaffey KW, Hedlin H, et al. Large-Scale Assessment of a Smartwatch to Identify Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(20):1909-1917. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1901183

3. Guo Y, Wang H, Zhang H, et al. Mobile Photoplethysmographic Technology to Detect Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(19):2365-2375. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.019

4. www.heartline.com

Rod Passman, MD

Professor, Feinberg School of Medicine

Cardiac Electrophysiology

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Wessling, E. Loke, D. (2021, Jan 25). Apple Heart Study. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Passman, R]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/apple-heart.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

1. Koshy, Anoop N., et al. "Smart watches for heart rate assessment in atrial arrhythmias." International journal of cardiology 266 (2018): 124-127.

2. Koshy, A., et al. "Heart Rate Assessment by Smart Watch: Utility or Futility?." Heart, Lung and Circulation 26 (2017): S280-S281.

3. Dörr, Marcus, et al. "The WATCH AF trial: SmartWATCHes for detection of atrial fibrillation." JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology5.2 (2019): 199-208.

4. Turakhia, Mintu P., et al. "Rationale and design of a large-scale, app-based study to identify cardiac arrhythmias using a smartwatch: The Apple Heart Study." American heart journal207 (2019): 66-75.

5. ACC News Story. “Apple Heart Study Identifies AFib in Small Group of Apple Watch Wearers.” American College of Cardiology: Latest in Cardiology, American College of Cardiology, 16 Mar. 2019, www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2019/03/08/15/32/sat-9am-apple-heart-study-acc-2019.

6. Morillo CA, Banerjee A, Perel P, Wood D, Jouven X. Atrial fibrillation: the current epidemic. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(3):195–203. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.03.011

7. Steinhubl SR, Waalen J, Edwards AM, et al. Effect of a Home-Based Wearable Continuous ECG Monitoring Patch on Detection of Undiagnosed Atrial Fibrillation: The mSToPS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA.2018;320(2):146–155.

8. Koshy, A., et al. "Cardiac Patients Likely to Seek Medical Assistance Based on Abnormal Heart Rate Readings on Smart Watches or Smartphone ECG Monitors." Heart, Lung and Circulation 26 (2017): S280.

9. Canalys Press Team. “18 Million Apple Watches Ship in 2017, up 54% on 2016.” Canalys Newsroom, Canalys, 6 Feb. 2018, www.canalys.com/newsroom/18-million-apple-watches-ship-2017-54-2016.

A “Pill-in-the-Pocket” Approach to Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation

Written by: David Feiger, MD (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Jon Andereck, MD, MBA NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Kaustubha Patil, MD

The Case

A healthy 65-year-old male with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation presents to the emergency department in atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate. His blood pressure is 135/83, heart rate 135, respirations 15 with an O2 saturation of 98% on room air. He states that he took his “pill-in-the-pocket” four hours prior to presentation and his symptoms did not resolve.

Atrial fibrillation

A study in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine in 2013 observed the costs associated with emergency department (ED) treatment and discharge of patients presenting with atrial fibrillation (AF) or atrial flutter was $5,460 [10]. Those admitted to the hospital naturally incur far higher costs. For those eligible, a visit to the ED could be avoided with the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach.

What is the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach?

The “pill-in-the-pocket” approach is the administration of a prescribed class IC antiarrhythmic, either flecainide or propafenone, following recent onset of episodes of palpitations in patients with paroxysmal AF. It is generally initiated by the patient’s cardiologist after extensive cardiac evaluation to rule out structural disease and other conduction abnormalities. The idea is to terminate the suspected episode of AF without having to present to an ED or clinic. Several studies have investigated the safety of this approach and supported this method of outside-the-hospital termination of paroxysmal AF events [2, 14].

Who is eligible for the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach?

In a study in the New England Journal of Medicine supporting the feasibility and safety of this out-of-hospital treatment, only specific patients were selected to participate. Inclusion criteria included:

healthier patients between 18 and 75 years old

a history of infrequent AF not associated with chest pain, hemodynamic instability, dyspnea, or syncope

no significant electrocardiographic abnormalities (pre-excitations, bundle branch blocks, long QT interval, etc.)

no structural or functional cardiac diseases

no history of thromboembolic episodes

no current use of an antiarrhythmic medication

not currently pregnant

no significant chronic disease including but not limited to muscular dystrophies, systemic collagen disease, and renal or hepatic insufficiency

These patients were then admitted to the hospital for a cardiac workup and were trialed on either flecainide or propafenone with successful pharmacologic cardioversion in the inpatient setting. Both flecainide and propafenone are proarrhythmic, thus structural heart diseases must be ruled out before their use and patients should be monitored during initiation of therapy [2].

How do flecainide and propafenone work?

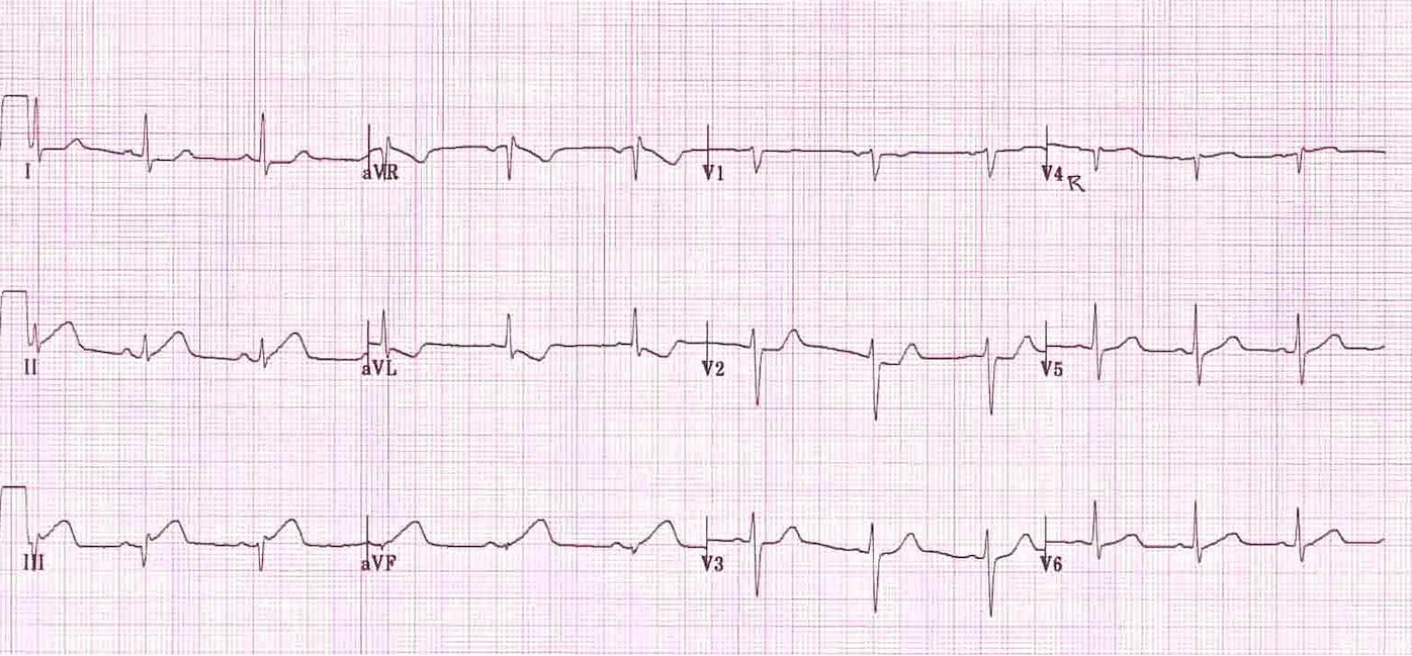

Flecainide and propafenone are both powerful class IC antiarrhythmics that strongly bind fast sodium channels with a slower association and dissociation than other class I antiarrhythmics. These drugs slow phase 0 during sodium-dependent depolarization in cardiac muscle cells of the atrial and ventricular myocardium (Figure 1). This effect is primarily important in prolonging atrial refractoriness, thus aiding in the conversion and termination of AF. Flecainide’s use in tachyarrhythmias comes from its rate-dependence property in which its efficacy is greater at faster heart rates. Propafenone has additional beta blocker activity which may enhance its overall clinical effectiveness in treating tachyarrhythmias [3, 5, 6, 13].

What are treatment options for patients presenting to the ED in AF?

For all comers presenting in AF with rapid ventricular rate to the ED, the literature has not elicited a perfect treatment modality, and no distinction is made for patients on the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach prior to arrival. Despite this, general practice guidelines are highlighted in many textbooks.

In hemodynamically-stable patients, rate control in the ED is the generally the treatment of choice. Diltiazem is often preferred as compared to beta blockers like metoprolol, which may cause hemodynamic instability in patients with underlying heart or lung disease. In otherwise healthy patients, metoprolol is a reasonable choice [1]. Digoxin is also appropriate, but onset takes several hours and is inferior to beta-blockers for rate control within 6 hours of treatment [11].

Patients who have been in AF for > 48 hours are at a greater risk of new intracardiac thrombus formation and cardioversion-induced embolization. Newer data from a study in 2014 suggests that there is an increased risk of thrombus formation with > 12 hours of AF [8] though the original guidelines for electric cardioversion within 48 hours of symptom onset have not changed. Patients who are hemodynamically stable who have been in AF for > 48 hours (and considered if > 12 hours) should be admitted from the ED for transesophageal echo to rule out intracardiac thrombus prior to cardioversion, or alternatively for initiation of anticoagulation [7].

In hemodynamically unstable patients, electrical cardioversion should be pursued regardless of a patient’s anticoagulation status [7].

Are there any treatment considerations in the ED for patients in AF taking flecainide or propafenone?

Treatment failure to the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach may be a marker of progression of the patient’s clinical disease. However, if a patient presents within an hour or two of taking their “pill-in-the-pocket,” remember the four to six-hour onset of these medications suggests they may convert during their ED stay. As in the case initially presented, the patient spontaneously converted while waiting for a provider. For those that do not, these patients warrant evaluation for new structural cardiac disease and may no longer benefit from the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach and may require daily maintenance prophylactic therapy [2].

A subset of stable patients presenting to the ED with AF with rapid ventricular rate may be taking flecainide or propafenone as maintenance therapy and not as part of the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach. In this instance, some literature has suggested that these patients can take an extra dose or two up to the maximum daily dose of flecainide (400mg) or propafenone (900mg for immediate release and 850mg for sustained release) to attempt pharmacological conversion, and it would be reasonable to attempt this in the ED [9].

To admit or not admit, that is the question.

The patient’s clinical picture should guide the provider as to the patient’s disposition. A patient’s comorbidities, current stability following conversion to normal sinus rhythm, plan for possible ablation, necessity for starting anticoagulation or maintenance medication, and means for close cardiology or PCP follow up on an outpatient basis should be factored when dispositioning the patient. Certainly, if a patient is requiring continuous IV infusion of rate controlling medications or has poor rate control, he or she should be admitted to the hospital [1]. Recent literature suggests that discharging stable patients home is safe following successful electrical, pharmacologic, or spontaneous cardioversion in the ED [4].

Final Thoughts

The “pill-in-the-pocket” approach is a great way for eligible patients to self-terminate episodes of AF in the comfort of their home, potentially preventing a costly and lengthy ED visit. While this approach has been shown to be a safe and effective for terminating paroxysmal AF, there is a significant lack of data on how to treat these patients who do not respond to these medications at home. General principals should be followed–electric cardioversion if the patient is hemodynamically unstable and rate control medications if the patient is hemodynamically stable (or rhythm control if you happen to practice in Canada [14]. Patients may be discharged home with close cardiology or PCP follow up if successfully cardioverted.

Expert Commentary

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and worldwide prevalence and incidence are increasing.1 It is estimated that by 2050 more than 12 million Americans will suffer from this debilitating and dangerous arrhythmia.1-2 AF presentations to Emergency Departments are certainly not without cost and the overall burden on the healthcare system will undoubtedly increase as the prevalence of atrial fibrillation continues to rise. A “pill in the pocket” approach for treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation has been well-described.

Class IC (sodium channel blockers) antiarrhythmic drugs (flecainide and propafenone) are the drugs of choice for “pill in the pocket” chemical cardioversion of symptomatic atrial fibrillation. There are some important considerations for this approach to be safe and effective:

The patient should have a history of infrequent paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, not persistent atrial fibrillation (episodes of AF that last greater than 7 days).

We reserve this approach for patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation (palpitations, mild dyspnea, or mild lightheadedness) with rapid ventricular rates who do not experience dangerous symptoms such as chest pain or syncope.

As anti-arrhythmic drugs can also be pro-arrhythmic, we do not recommend Class IC antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with known structural heart disease, reduced left ventricular systolic function, or known coronary artery disease, due to the increased risk of inducing dangerous arrhythmias.

In patients who are not on therapeutic anticoagulation, we only recommend this approach when it has been less than 24 hours since onset of the AF episode. If the AF episode has lasted beyond 24 hours or it is unknown when the episode started, the risk of formation of intracardiac thrombus during AF and subsequent risk of stroke after a successful chemical cardioversion from a Class IC drug would be prohibitively high.

Due to the use-dependent nature of Class IC antiarrhythmics (more effective with more sodium channel blockade at faster ventricular rates), there is a chance of slowing conduction throughout the heart to the point that atrial fibrillation can organize into rapid atrial flutter with 1:1 AV conduction, leading to an aberrant wide complex tachycardia. For this reason, we recommend that the patient receive a beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker at least 30 minutes prior to administration of flecainide or propafenone.

Some practitioners recommend that if the patient is not already on anticoagulation, that they initiate anticoagulation at the time of beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker administration to reduce the risk of intracardiac thrombus formation if the patient does not convert to sinus rhythm within 24-48 hours.

Some practitioners recommend that the first attempt at “pill in the pocket” dosing be performed in the emergency department so that safety and efficacy can be monitored.

If patients report a progressively increasing need for “pill in the pocket” use or there is a suggestion of increasing burden of AF episodes, I recommend consultation with the patient’s cardiologist or electrophysiologist to discuss alternative options for rhythm control of symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Potential options at that time could include initiation of maintenance antiarrhythmic drug therapy versus invasive management with catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation.

When used in the right patient, a “pill in the pocket” approach can be a very effective strategy for rhythm control of infrequent symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Appropriate patient factors to consider prior to recommending this approach are nicely highlighted in the post above. “Pill in the pocket” management for AF can resolve patient symptoms, improve patient’s quality of life, and reduce unnecessary emergency room visits and subsequent hospitalizations.

References

Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014 Feb 25; 129(8):837-47.

Miyasaka Y, Barnes M, Gersh B, et al. Secular Trends in Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and Implications on the Projections for Future Prevalence. Circulation. 2006 Jul 11;114(2):119-25.

Kaustubha Patil, MD

Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology

Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute Northwestern Medicine

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Feiger, D. Andereck, J. (2020, Nov 2). A “Pill-in-the-Pocket” approach to paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Patil, K]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/pill-in-pocket.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Adams, James, et al. “Tachydysrhythmias.” Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials, Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013, pp. 497–513.

Alboni, Paolo, et al. “Outpatient Treatment of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation with the ‘Pill-in-the-Pocket’ Approach.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 351, no. 23, 2004, pp. 2384–2391., doi:10.1056/nejmoa041233.

Aliot, E., et al. “Twenty-Five Years in the Making: Flecainide Is Safe and Effective for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation.” Europace, vol. 13, no. 2, 2010, pp. 161–173., doi:10.1093/europace/euq382.

Besser, Kiera Von, and Angela M. Mills. “Is Discharge to Home After Emergency Department Cardioversion Safe for the Treatment of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation?” Annals of Emergency Medicine, vol. 58, no. 6, 2011, pp. 517–520., doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.06.014.

Dan, Gheorghe-Andrei, et al. “Antiarrhythmic Drugs–Clinical Use and Clinical Decision Making: a Consensus Document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacology, Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS) and International Society of Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy (ISCP).” EP Europace, vol. 20, no. 5, 2018, doi:10.1093/europace/eux373.

Dukes, I.d., and E.m Vaughan Williams. “The Multiple Modes of Action of Propafenone.” European Heart Journal, vol. 5, no. 2, 1984, pp. 115–125., doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061621.

January, Craig T., et al. “2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 64, no. 21, 2014, doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022.

Nuotio, Ilpo, et al. “Time to Cardioversion for Acute Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolic Complications.” Jama, vol. 312, no. 6, 2014, p. 647., doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3824.

“Pill-in-a-Pocket Dosing Safely Converts Breakthrough Atrial Fib.” Family Practice News, vol. 35, no. 18, 2005, p. 20., doi:10.1016/s0300-7073(05)71733-3.

Sacchetti, Alfred, et al. “Impact of Emergency Department Management of Atrial Fibrillation on Hospital Charges.” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, vol. 14, no. 1, 2013, pp. 55–57., doi:10.5811/westjem.2012.1.6893.

Sethi, Naqash J., et al. “Digoxin for Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials.” Plos One, vol. 13, no. 3, 2018, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0193924.

Stiell, Ian G., et al. “Association of the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol with Rapid Discharge of Emergency Department Patients with Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter.” Cjem, vol. 12, no. 03, 2010, pp. 181–191., doi:10.1017/s1481803500012227.

Wang, Z, et al. “Mechanism of Flecainide's Rate-Dependent Actions on Action Potential Duration in Canine Atrial Tissue.” American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, vol. 267, no. 2, 1 Nov. 1993, pp. 575–581.

Yao, R., et al. “Real-World Safety And Efficacy Of A ‘Pill-In-The-Pocket' Approach For The Management Of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation.” Canadian Journal of Cardiology, vol. 33, no. 10, 2017, doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.07.371.

Canadian Syncope

Written by: Jonathan Hung, MD (NUEM ‘21) Edited by: Jon Anderek (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Andrew Moore, MD, MS

Introduction

Syncope is defined as a brief loss of consciousness that is self-limited. [1] It is a commonly seen chief complaint in the emergency department (ED), consisting of up to 3% of ED visits. [2] There are both benign causes of syncope such as vasovagal syncope and more serious causes such as arrhythmias. By the time these patients present to the ED, they are often asymptomatic and hemodynamically stable. Part of the ED workup and disposition includes risk stratification of these patients that can vary by provider and hospital system. [3] For those who present with high-risk features, ED physicians often recommend admission to the hospital for telemetry monitoring and expedited evaluation with echocardiography. [4] Multiple decision rules, most notably the San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR), have been developed to identify syncope patients at risk for poor outcomes. The SFSR takes into account predictors such as a history of heart failure, an abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG), and hypotension to determine 7-day negative outcomes for patients presenting to the ED with syncope. [5] Another study called the Osservatorio Epidemiologico sulla Sincope nel Lazio (OESIL) includes age over 65 and syncope without prodrome in addition to a history of cardiovascular disease as part of their decision-making tool. [6] Lastly, the Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department (ROSE) also takes lab results such as brain natriuretic peptide and hemoglobin into account. [7] Despite the numerous studies examining risk stratification in syncope, each one has limitations and ultimately lack adequate sensitivity and specificity for widespread clinical adoption. A new study published in Academic Emergency Medicine is one of the largest studies to develop a risk tool that identifies adult syncope patients at 30-day risk for serious adverse outcomes defined as a serious arrhythmia, need for intervention to correct arrhythmia, or death. [8]

Study

Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Stiell IG, Sivilotti MLA, et al. Predicting Short-term Risk of Arrhythmia among Patients With Syncope: The Canadian Syncope Arrhythmia Risk Score. Baumann BM, ed. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(11):1315-1326.

Study Design

Multi-center, prospective, observational cohort study.

This was a derivation study used to define the parameters of the risk score.

Population

Inclusion criteria:

Syncope patients presenting within 24 hours of the event

Adults age ≥16

Exclusion criteria:

Prolonged loss of consciousness

Change in mental status from baseline

Witnessed seizure

Head trauma or other trauma requiring admission

Unable to provide history due to alcohol intoxication, illicit drug use or language barrier

Obvious arrhythmia or nonarrhythmic serious condition on presentation

Intervention protocol

ED physicians and emergency medicine residents were trained to assess standardized variables at the initial ED visit including time and date of syncope, event characteristics, personal and family history of cardiovascular disease, and final ED diagnosis. Other variables were obtained through chart review and included age, sex, vital signs, laboratory results and ECG variables. All ECGs were reviewed by a cardiologist, and abnormal variables were reviewed by a second cardiologist. Physician gestalt for dangerous etiology was also recorded for each patient. Multivariable logistic regression was used for the analysis.

Outcome Measures

Composite of death, arrhythmia, or procedural interventions to treat arrhythmias within 30 days of ED disposition

Results

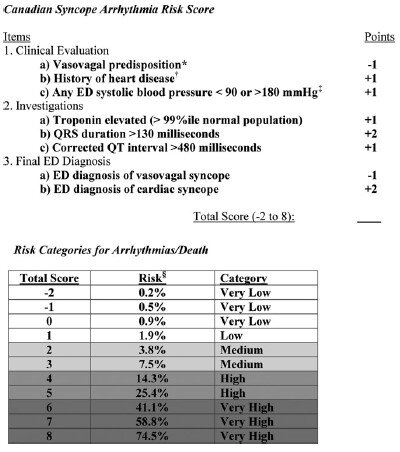

5,010 patients were enrolled in the study with 106 (2.1%) patients suffering arrhythmia or death within 30 days of ED presentation. Forty-five of the 106 patients suffered their adverse event outside of the hospital. The mean age of the study population was 53.4 (SD 23.0 years) and 54.8% were females. A total of 8 variables were included in the final model:

Vasovagal predisposition

History of heart disease (CAD, atrial fibrillation/flutter, CHF, valvular abnormalities)

Systolic blood pressure <90 or >180 mm Hg at any point

Troponin elevation

QRS duration >130 msec

QTc interval > 480 msec

ED diagnosis of cardiac syncope

ED diagnosis of vasovagal syncope

The Canadian Syncope Arrhythmia Risk Score had a sensitivity of 97.1% and specificity of 53.4% at a threshold score of 0 based on the study’s internal validation.

Interpretation

This study is the largest, multicenter study assessing predictors of short-term outcomes following initial ED presentation of syncope. The results are similar to previous studies that examined long-term outcomes. One interesting difference is that in prior studies, advanced age was a risk factor in arrhythmia or death, however it did not make the final model in this study. The strengths of this prospective study include the large patient population and that only 6.5% were lost to follow up. Furthermore, developing a simplified risk tool similar to the HEART score for chest pain, it can be easily utilized in the ED to help aid in decision making. Some limitations are that a large portion (54%) of patients did not have a troponin level measured and the study notes that these were usually younger patients with less comorbidities.

In practice, it may be difficult to use this tool if there is provider variation for when cardiac syncope is suspected and when a troponin level is measured. Whether or not the provider diagnoses vasovagal syncope or cardiac syncope is subjective as well, though may serve as a surrogate for “physician gestalt.” These results are helpful in risk stratifying syncope patients especially in regard to short-term outcomes, however this disease process is complex and cannot be oversimplified. Overall, this decision tool at the very least allows ED providers to have a shared decision-making conversation with more robust data to support the various options.

Take Home Points

The Canadian Syncope Arrhythmia Risk Score is a large, multicenter trial evaluating serious 30-day outcomes following an ED presentation for syncope

Emergency medicine physicians may consider using this tool to guide their clinical-decision making for syncope patients by offering risk percentages for 30-day adverse events

At the time this was written a validation study was underway

Expert Commentary

The management and disposition of syncope has been a conundrum for emergency physicians for decades. In fact, the last 20 years of syncope research have focused on development of a risk stratification score for the ED management of syncope. With the recent external validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Stratification Score [9] (CSRSS) and the recent publication of the FAINT Score [10] for syncope in older adults, we now have two prospectively derived studies to support risk stratification of the syncope patient. The external validation of the CSRSS showed good sensitivity for low risk patients with a sensitivity of 97.8%. None of the very low risk or low risk patients in the external validation died or suffered cardiac arrhythmia in 30 days. Based on this if your patient is very low risk or low risk you can safely discharge the patient home with primary care follow up.

In my practice, the CSRSS serves as an adjunct to clinician judgement. Using a risk stratification score is often the impetus for a shared decision-making discussion regarding risk and safe disposition. The results of the external validation study further support clinical use of the CSRSS.