Written by: August Grace, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Andrew Rogers, MD, MBA (NUEM ‘22)

Expert Commentary by: Andra Farcas, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Introduction

In the setting of trauma, most hospitals are adept at treating and managing patients with a variety of injuries. However, the ability of a hospital to handle a mass casualty incident (MCI) requires a completely different approach and, most importantly, adequate triage and pre-planning. An MCI is defined as “an event that overwhelms the local healthcare system, where the number of casualties vastly exceeds the local resources and capabilities in a short period of time [7].” MCI events can include anything from hurricanes, earthquakes, and other natural disasters to terrorism or other man-made situations that include the use of explosive or biological weapons, mass shootings, or dysfunction in modes of transportation (car, plane, train crash) [3]. Although this is just a short list of the possibilities, each hospital must prioritize its response preparedness to match the likelihood of events that it could receive. For example, as a major urban center, Chicago is more likely to encounter events such as mass shootings, biological terrorism, or explosive injuries. Mobile, Alabama, on the other hand, must have adequate preparation for hurricanes and floods [4]. This post will discuss a brief overview of hospital planning and operational setup with key elements of a disaster response from events that cause high numbers of blunt trauma, penetrating trauma, burns or crush injuries that may be seen following explosive events, mass shootings, or large scale motor vehicle collisions, to name a few.

Casualty Planning & Staffing Considerations

Arguably the most important step in an MCI is the planning that occurs before a single patient is even seen. In most events, hospitals have communication with EMS personnel that are on scene allowing them to have some sort of estimation of the scale of the event and type of disaster encountered. If the mechanism and scale are appropriate, a properly planned disaster response should be initiated and set in motion a sequence of coordinated events.

In creating a disaster response plan, the first step is the designation of the Disaster Medical Officer (DMO). This person should be the most senior ED attending physician and he/she oversees available hospital medical personnel and resources [1]. This person will have no role in patient care and instead will be in charge of all ED operations, delegating tasks, and problem solving issues that arise in the future.

The first task of the DMO is to get help and get it now. Approximately half of all casualties will arrive at the hospital within a one hour window, with 50-80% arriving within 90 minutes. Time begins after the first patient arrives at the hospital [8]. Therefore, getting the appropriate staff to the hospital as quickly as possible is vital to saving lives. How much staff is needed? This can be gauged by the type of disaster encountered and with assistance from EMS personnel at the scene. A five-car motor vehicle collision (MVC) will not require as much additional staff as a collapsed high rise building. The DMO will delegate the task of calling available staff to maximize the number of staff present in the ED and hospital. Contacting surgeons, scrub techs, anesthesiologists, and nurses to get as many ORs operational is invaluable to saving lives.

Continuous staffing adjustments can be monitored and made by using the casualty predictor tool (Figure 2). When in doubt, it is better to have more staff available than needed. To reiterate, the most important part of any disaster situation is to GET HELP.

Triage/ED Setup

Once the process is underway for increasing the level of resources available, the next step is hospital setup and triage. The most important part of this step is creating enough space to allow for the massive influx of patients and maintaining proper flow throughout the ED. It is well known that most hospitals in large population centers already operate at or near full capacity [4]. This makes it even more challenging when presented with an acute influx of patients in a short period of time. There is not much that can be done in the acute setting about patients that are already admitted; however, the ED can be restructured to account for the increased surge. Patients currently in the ED with a condition deemed to be stable (will likely not require an acute intervention in the next 24 hours) can be moved to a different area (green triage area, discussed below). The patients who have a more acute condition can be triaged and recategorized using the same criteria as the incoming casualties.

One current method of triaging patients is the tagging method. In this system, patients are tagged with a red, yellow, or green identification that categorizes patients based on acuity. Other things listed on tags can be a patient’s name, bar code, MRN or other tracking criteria. These patients are then able to be treated based on the level of care needed. In theory, this is a good way for patients to be tracked and accounted for. However, some experts believe that when there is a large volume of patients, this can slow the triage process and extend the amount of time it takes the patient to receive care that may be lifesaving. Another limitation is that it does not allow for a dynamic system, it provides a false sense of security, and can cause confusion. For example, a patient may have a green tag when initially triaged but could decompensate to a yellow or red tag [6]. Thus, there should be an appropriate system for re-evaluation if resources allow.

One system that could be used instead is a tag zone. In this system, the ED could be set up into different zones that would correlate with the tag color and acuity of the condition. Who should triage? The second most senior ED attending physician. The zone system could be set up as follows:

Red zone: Patients that need immediate medical or surgical attention. This includes patients presenting with an acute airway, circulatory or neurologic problem, multi-system involvement, or penetrating injuries to the head, neck, or chest. These patients are likely to need the vast majority of resources and staff.

Orange zone: Not originally categorized in the tag system. These patients are expected to decompensate within the hour but did not need immediate resuscitation [2].

Yellow zone: Patients that are relatively stable that will likely not decompensate within the hour. Extremity injuries or conditions that have time to be worked up.

Green zone: Patients with minor injuries that are unlikely to decompensate. “Walking wounded.” Will not require vast amounts of resources or staffing to be cared for.

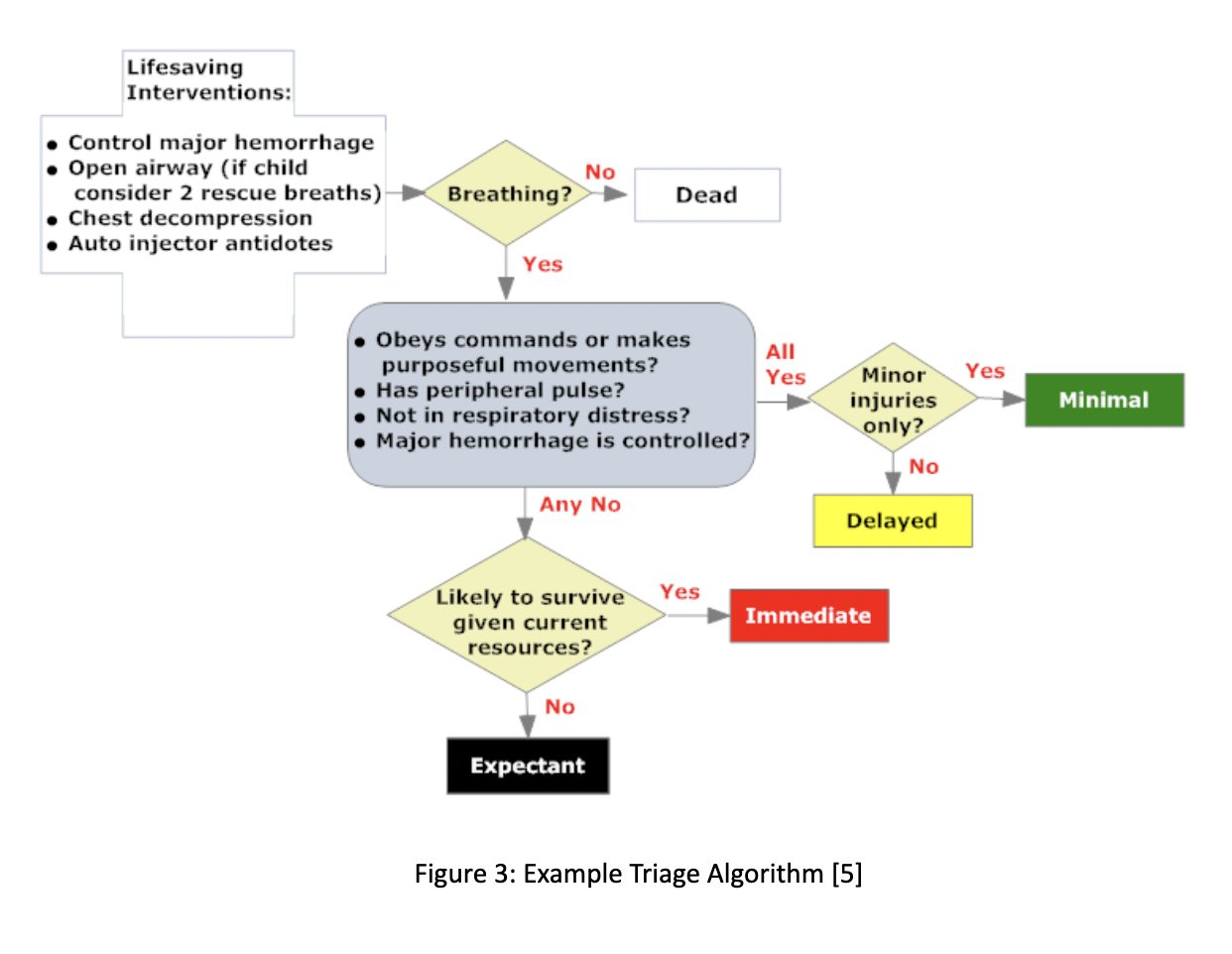

The different zones allow for a dynamic system. Patients in each zone will be cared for by a team of physicians and nurses with the majority of staffing located in Red and Orange zones. Patients can be moved “up” a zone (from yellow to orange) if their condition deteriorates or could be moved “down” a zone (from yellow to green) if they are able to be stabilized [1, 2, 3]. The “black tag” patients were not categorized into a zone as they were patients who were either already dead, or not likely to survive given the current staffing and resources available. Figure 3 shows a brief triaging algorithm (without the orange designation). This is one possible system to triage patients and get them to an appropriate level of care rapidly. The hospital system is now ready for the rapid influx of critical patients.

Implementation

All patients should enter through a single triage area. Multiple points of entry can cause confusion and overwhelm each area by not knowing the number of patients entering from each point [4]. As the number of patients in each zone starts to fill up, adequate communication about the space and number of resources available should be communicated to the DMO and charge nurse. Once patients are able to be stabilized in each zone, the goal is to get them to the OR for immediate surgery if needed, or to move them down a zone (yellow to green) in order to make space for additional critically injured patients.

Who are the first patients to arrive? The “dual wave phenomenon” explains how patients usually present to the hospital following MCIs. The first wave of casualties are described as the “walking wounded” or those who are able to self-ambulate and usually only require minor care. These patients begin to arrive within 15-30 minutes of the incident depending on the distance from the scene to the hospital. It is important that these patients do not take up too many hospital resources or staff as they are likely well enough to survive with minimal therapeutic interventions. These patients can easily overwhelm the system and prevent proper care to more critical patients. The second wave includes the patients that arrive via EMS or other assistance from bystanders as they are not well enough to transport themselves. These are the patients who will require a vast majority of hospital staffing, resources, and time in order to prevent deaths [3, 4].

Summary

The first step to preparing for an MCI is having a plan in place.

GET HELP. If you only have time to do one thing it should be this. It does not matter how many resources you have or how much space is available if you do not have enough staff to use them.

Have a triage plan. Create zones of various acuity with the majority of staff occupying the higher acuity areas. Patients can always be moved to a higher zone if they need more care or a lower zone if they have been stabilized.

Get patients to the proper provider. If the patient needs surgery, get them to the OR. This also creates space for new patients to be seen.

Have one single area of entry. This allows the system to maintain consistency and flow.

References

Emergency Safety Officer Management Plan For Mass Casualty. Kings County Hospital Center, www.downstate.edu/emergency_medicine/pdf/KCHCSection03.pdf.

Menes, Kevin. “How One Las Vegas ED Saved Hundreds of Lives After the Worst Mass Shooting in U.S. History: Emergency Physicians Monthly.” EPM, 5 Apr. 2020, epmonthly.com/article/not-heroes-wear-capes-one-las-vegas-ed-saved-hundreds-lives-worst-mass-shooting-u-s-history/.

Hospital Medical Surge Planning for Mass Casualty Incidents. Florida Department of Health, www.urmc.rochester.edu/MediaLibraries/URMCMedia/flrtc/documents/WNY-Hospital-Medical-Surge-Planning-For-Mass-Casualty-Incidents.pdf.

Institute of Medicine. 2007. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11621

“SALT Mass Casualty Triage Algorithm - CHEMM.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, chemm.nlm.nih.gov/salttriage.htm.

“Report: Mass Casualty Trauma Triage Paradigms and Pitfalls .” Journal of Emergency Medical Services , Office of the United States Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Disaster Response.

DeNolf, Renee L. “EMS Mass Casualty Management.” StatPearls [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 15 Oct. 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482373/.

“Mass Casualty Predictor .” Homeland Security Digital Library , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention .

Expert Commentary

This is a great review of MCI management in the Emergency Department by Drs. Grace and Rogers. Although the past few years of the COVID-19 pandemic have felt like we’ve been working in a perpetual MCI, these are important principles to review on a regular basis, as they are not something we necessarily practice every day in the emergency department.

The authors do a good job of emphasizing the importance of preparing for an MCI ahead of time. Another important aspect of preparation is decontamination. An ED disaster response plan should incorporate how to effectively put patients (both walk-ins and EMS arrivals) through decontamination if the disaster at hand requires it. The authors emphasize the importance of having patients enter through a single triage area, and the decontamination station should be similarly set up nearby allowing for one-directional flow of patients through the decontamination process. This is not only vital to patient treatment but also to ensuring staff safety. Additionally, it is necessary to ensure that the ED has sufficient and adequate level Personal Protective Equipment and that the appropriate staff are trained on donning/doffing procedures.

In addition to gathering the staffing resources, there should also be an emphasis on gathering disaster-specific supplies: alerting the blood bank if it is a traumatic MCI, amassing antidotes if it is toxicological in nature, compiling medical equipment (such as ventilators) as applicable, etc. Additionally, alerting other EDs in the system as to the impending influx of patients as well as reaching out to disaster-specific specialty centers (ie, hyperbarics facility for a structure fire for carbon monoxide treatment) can also help take pressure off and allocate more resources.

Finally, the importance of a hotwash or after-action review cannot be emphasized enough. This is a process by which participants can have an open and honest professional discussion about what went well and what can be improved in the future. It centers around four main questions (What was supposed to happen? What did happen? What caused the difference? What can we learn from this?) and is vital for building an ED’s capacity for conducting an adequate emergency response to an MCI.

References

Blackwell, T.H., DeAtley, C., Yee, A. (2021). Medical support for hazardous materials response. Cone, D.C. (ed). Emergency Medical Services Clinical Practice and Systems Oversight; Volume 2: Medical Oversight of EMS. (3rd edition, p339-351). UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.

Greenberg, T., Adini, B., Eden, F., Chen, T., Ankri, T., Aharonson-Daniel, L. An after-action review tool for EDs: learning from mass casualty incidents. Am J Emerg Med. May 2013;31(5):798-802. Doi 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.025. Epub 2013 Mar 6. PMID: 23481154.

Metz, T. How to Facilitate an After-Action Review (AAR or Hot Wash): Agenda and Tips. MG Rush Facilitation Training & Meeting Design. https://mgrush.com/blog/after-action-review/.

Salem-Schatz, S., Ordin, D., Mittman, B. Guide to the after action review. Center for Evidence-Based Management. Oct 2010. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Guide-to-the-after_action_review.pdf.

Andra Farcas, MD

Emergency Medicine & EMS Physician

CU Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Colorado School of Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Grace, A. Rogers, A. (2021, Apr 26). Proper Preparation for Mass Casualty Incidents. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Farcas, A]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/mass-casualty-incident-preparation