Author: John Andereck, MD (EM Resident Physician, PGY-2, NUEM) // Edited by: Grant Scott, MD // Expert Commentary: James Walter, MD

Citation: [Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Andereck J, Scott G(2016, September 6). Vocal Cord Dysfunction [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary By Walter J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/vocal-cord-dysfunction/

The Case

A middle aged woman presents for “asthma exacerbation” and is triaged as ESI 2 with vital signs of T 97.6, HR 111, RR 24, BP 118/61, and Sat 98% on room air. In the room she is tripoding on the bed in terrible respiratory distress and can only answer questions with nodding or shaking her head. Time to mobilize.

While starting a continuous nebulizer treatment, administering 125 mg IV methylprednisolone and 2 g IV magnesium, and setting up for a potential airway, we use yes or no questions to get a history. She has asthma, has been on steroids for the past five days, and has been using her nebulizer at home constantly with no improvement. She has had a persistent dry cough (which I note frequently on exam) that triggered this exacerbation, but no fevers or chills. No history of allergy or anaphylaxis. She has been to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) before and was intubated one time about 18 months prior.

On exam, I count her respirations at 60/minute with a heart rate in the 120s on the monitor. Her oxygen saturation remains 98-100% on non-rebreather and she is normotensive. She has no neck swelling. On lung exam, she is using accessory muscles and has virtually no air movement with very soft inspiratory “squeaking” and expiratory wheezes.

After about 20 minutes with continuous nebulized albuterol-ipratropium her tachypnea hardly improves and she is only moving slightly more air. Despite her tachypnea and apparent respiratory distress, she is able to text on her phone and lay forward on the bed, which she says is more comfortable. The picture just does not quite fit. Nevertheless, due to her persistent work of breathing, we decide to give 0.3 mg IM epinephrine, place her on non invasive ventilation (NIPPV), and consult the MICU.

On NIPPV, her respiratory rate improves and she is noted to have much more significant inspiratory stridor in addition to expiratory wheezing. As significant as her work of breathing is, and as little improvement as she had with our multiple interventions, she is not decompensating and has maintained more than adequate saturations throughout her entire emergency department stay. When the MICU resident called back, he asked: “does she even have asthma?” She had been evaluated in pulmonary clinic recently where her existing diagnosis of cough-variant asthma had been questioned and the possibility of vocal cord dysfunction was raised.

Once in the MICU, she was started on heliox and remained on NIPPV for the next 24 hours but never required intubation. ENT was consulted and laryngoscopy demonstrated paradoxical vocal cord motion on inspiration consistent with vocal cord dysfunction. She was discharged from the MICU the next day.

Vocal Cord Dysfunction

Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) is a condition characterized by paradoxical vocal fold motion with inspiration leading to stridor, air hunger, tachypnea, chest tightness, and a feeling of suffocation [1-3]. A number of different triggers for VCD have been identified since the condition was first described in 1974. Initially, this was thought to be a purely psychiatric condition that was a form of conversion disorder, initially termed “Munchausen’s Stridor” by Patterson et al [4]. While many patients with VCD do carry psychiatric diagnoses, exercise, irritants (reflux of gastric contents, upper respiratory infections, post-nasal drip), and asthma have been identified as other triggers [2]. The interplay of asthma and VCD has been difficult to establish. Estimates of concomitant asthma diagnoses range from one third to one half of all patients with VCD, however it is common for patients with VCD to be completely misdiagnosed – often for years – as having refractory asthma [2,5,6].

Figure 1. Graphical representation of normal vocal cord abduction during inspiration (left) and inappropriate paradoxical vocal cord adduction with a characteristic posterior “chink” in VCD (right) [7].

Diagnosis of VCD is three-fold: (1) clinical symptoms of intermittent stridor; (2) laryngoscopic evidence of paradoxical vocal cord adduction during inspiration, often demonstrating the characteristic posterior “chink” (Figure 1); and (3) pulmonary function tests (PFTs) demonstrating lack of significant bronchospasm and presence of a flattened inspiratory flow volume loop (Figure 2) [2,6]. Clearly we will not be diagnosing VCD in the emergency department (ED) with these diagnostic criteria, so our suspicion must be clinical and must include a broad differential of other causes of upper airway obstruction and respiratory distress (Figure 3).

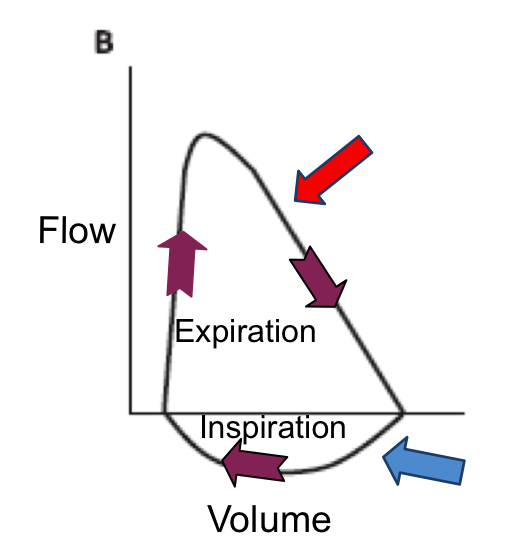

Figure 2. Flow-volume loop. (Left) Normal expiratory and inspiratory loop. (Right) Normal expiratory loop with flattening of the inspiratory loop, consistent with vocal cord dysfunction. Borrowed from Deckert and Deckert (2010) [6].

Recommended ED Approach

In general, VCD should be a diagnosis of exclusion in the ED – the risk of missing something more life threatening is high and none of us should be too cavalier about making this diagnosis in someone who does not already have confirmed VCD by laryngoscopy and PFTs. However, there are features that may suggest it.

Figure 3. Cues to trigger suspicion for VCD as well as other potential causes of the presenting symptoms.

In cases in which the suspicion for VCD is high and the management of asthma (as in our case) or other upper airway issue has been unsuccessful, then consider VCD specific interventions in an effort to avoid an unnecessary intubation.

I like to break up the emergent management of VCD into three primary components: treating the life threats, specific interventions for VCD, and anxiolysis.

- Treating the life threats: Once again, the worst thing to do in VCD is to miss the more serious diagnosis. An exacerbation of VCD can present for all the world like status asthmaticus, anaphylaxis, or foreign body aspiration. Treat initially with nebulizers, oxygen, steroids, magnesium, epinephrine, and x-ray before proceeding. If the clinical course is not improving as expected, then move on to #2.

- VCD-specific support: There are a number of breathing techniques that have been described to help open up the airway. These include pursed lips breathing, blowing through a short straw to move the obstruction to the lips rather than the glottis, making an “s” sound on expiration, or rapid panting in an effort to activate the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles [1, 5]. There are reports of inhaled heliox (70-80% helium, 20-30% oxygen) being used in VCD exacerbations as the lighter helium helps decrease turbulent flow across the narrowed cords [5,6].

- Anxiolysis: These patients are often extraordinarily anxious and are in need of reassurance that their oxygen saturation is fine despite their feeling of air hunger [5]. In many cases, trialling low doses of benzodiazepines will help slow the respirations and calm the patient. Sub-dissociative doses of ketamine have also been reported multiple times to help break the VCD flare, though if you are going to push ketamine be ready to paralyze and intubate as this may cause worsening laryngospasm [3].

VCD is rare, but not as rare as you might think. If you have a patient that is tachypneic with wheezing or inspiratory stridor but not actually crashing, consider whether you can save them a tube by thinking about this deceptive diagnosis.

Take-Home Pearls

VCD is a scary condition that often mimics status asthmaticus, foreign body aspiration, or anaphylaxis.

Treat VCD initially as a life threat, especially if the patient does not already carry a confirmed diagnosis (with direct laryngoscopy and PFTs).

If something in the presentation does not add up (tachypnea without hypoxia, respiratory distress that is not positional, etc.) and if the patient’s course is not improving significantly with maximal therapy, ask whether this could be VCD.

- If VCD is suspected, try heliox, pursed lips breathing, panting, and anxiolysis (benzodiazepines vs. ketamine).

- Thinking of VCD with stridulous patients in distress can lead to early appropriate therapy and can potentially save patients an intubation and a trip to the ICU.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on this thoughtful review of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD). This is an important yet easily overlooked clinical entity for emergency physicians, internists, and pulmonologists. I’ve organized my feedback into several key themes.

Key Take-Home Point

- Pulmonologists most commonly see these patients in clinic for work-up of severe persistent asthma or chronic cough. In the outpatient setting, there is time for a detailed history and step-wise diagnostic testing. As emergency physicians, you will encounter these patients when they are acutely symptomatic, often with striking clinical features as presented in the case. While VCD is an important diagnostic consideration in a patient with a history of difficult-to-control asthma, you correctly emphasize that emergency physicians should always treat an acutely ill patient with suspected asthma with therapies to reduce bronchoconstriction even when there is suspicion for VCD. You mention, “none of us should be too cavalier about making this diagnosis in someone who does not already have VCD confirmed by laryngoscopy or PFTs.” I would argue that even in a patient with previously confirmed VCD, the default for emergency physicians should still be to treat these patients aggressively for asthma. As you note, there is substantial overlap between VCD and asthma (over 50% of patients with VCD may have concurrent asthma [8]). As a result, a prior diagnosis of VCD should not reassure clinicians that an acute flare of symptoms is explained entirely by VCD.

- The case described has many concerning features in both the history (persistent symptoms despite steroids/frequent short-acting bronchodilator use and a history of prior intubations) and exam (marked tachypnea, severe distress, and poor air movement). These red flags along with the prolonged nature of the symptoms and expiratory wheezing (both of which are atypical for VCD) should prompt immediate and aggressive therapy for presumed status asthmaticus before alternative explanations are considered (as was done).

Our Evolving Understanding Of VCD Epidemiology And Pathophysiology

- You correctly describe the evolution in our understanding of VCD epidemiology. The typical board question for VCD focuses on a middle-aged female healthcare worker with generalized anxiety disorder or a history of abuse. This is based on early studies including the work by Patterson that you cite. We now recognize that while VCD does seem to be more common in females, it is also commonly diagnosed in men and is identified in patients of all ages [9].

- There is growing evidence that a wide range of co-morbid conditions beyond psychiatric disease may precipitate or contribute to VCD. One of the major pathogenic mechanisms is laryngeal hyper-responsiveness which may be triggered by post-nasal drip or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [9,10]. A variety of neurologic disorders and direct trauma to the larynx (from either surgery or endotracheal intubation) have also been linked to VCD [9]. In clinic, we take a detailed history for symptoms of post-nasal drip and GERD for any patient with suspected or confirmed VCD and treat aggressively if either condition is suspected. It is also worth noting that post-nasal drip and GERD are frequent contributors to suboptimal asthma control.

Clinical Features

Your table “when to suspect VCD” nicely summarizes common clinical features in patients with VCD. It is worth emphasizing that many of these features are also found in patients with severe persistent asthma (frequent ED visits, no response to asthma therapy, more than five intubations) and should not be viewed as definitive evidence that the patient does not have asthma.

- A recent review in the European Respiratory Journal has a helpful table comparing asthma with VCD [11]:

- For me, the localization to the throat and perceived dyspnea during inspiration are the most helpful features that distinguish VCD from asthma (although certainly not 100% sensitive or specific for VCD).

Variable Extrathoracic Obstruction

As this is the hallmark finding of VCD on spirometry, it is important to understand the underlying physiology (images are from a nice physiology discussion published in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society [12]).

- The key pressures involved are alveolar pressure (the sum of lung elastic recoil pressure and pleural pressure) and airway transmural pressure (pressure inside the airway minus pressure outside the airway)

- To illustrate how these pressures change with tidal breathing, note the figures below.

- With a variable extra-thoracic obstruction (due to laryngeal pathology like VCD), inspiration causes a drop in airway transmural pressure, narrows the caliber of the large airway, and reduces flow. This causes flattening of the inspiratory limb of the flow volume loop that is characteristic of VCD (blue arrow)

- The obstruction is “variable” because forced expiration causes a rise in airway transmural pressure, dilating the airway and relieving the obstruction so the expiratory limb of the flow volume loop appears normal (red arrow). In asthma, the expiratory limb can appear scooped like is classically seen in COPD. Importantly, spirometry is usually normal when a patient is asymptomatic.

Diagnosis

- As you mention, the gold standard is direct visualization of vocal cords while a patient is symptomatic (which can be induced with methacholine or exercise).

- If there is a concern regarding potential VCD in the ED, an ENT consult for a fiberoptic upper airway examination can be very helpful to document paradoxical adduction of the vocal cords.

- Other potential diagnostic tests such as dynamic upper airway CT are not as relevant to EM [13].

Treatment

- There is little prospective data to guide treatment. As you mention, initial treatment in the ED treatment should be directed at potential asthma.

- Positive airway pressure (via CPAP or BiPAP) can be helpful [9] and there is some data regarding the beneficial effects of heliox [14] although I have not seen it used.

James Walter, MD

Clinical Fellow; Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care; Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Mikita, J.A. and C.P. Mikita, Vocal cord dysfunction. Allergy Asthma Proc, 2006. 27(4): p. 411-4.

Morris, M.J. and K.L. Christopher, Diagnostic criteria for the classification of vocal cord dysfunction. Chest, 2010. 138(5): p. 1213-23.

Farney, A., et al., It is Hard to Breathe When Your Vocal Cords Don't Work!, in EM:RAP. 2015.

Patterson, R., M. Schatz, and M. Horton, Munchausen's stridor: non-organic laryngeal obstruction. Clin Allergy, 1974. 4(3): p. 307-10.

Humfeld, A. and M.L. Mintz, Vocal Cord Dysfunction, in Disorders of the Respiratory Tract: Common Challenges in Primary Care, M.L. Mintz, Editor. 2006, Humana Press: Totowa, NJ. p. 279-287.

Deckert, J. and L. Deckert, Vocal cord dysfunction. Am Fam Physician, 2010. 81(2): p. 156-9.

Buddiga, P. Vocal Cord Dysfunction. [cited 2016 April 20]; Available from: http://misc.medscape.com/pi/iphone/medscapeapp/html/A137782-business.html.

Newman KB, Mason UG, 3rd, Schmaling KB. Clinical features of vocal cord dysfunction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Oct 1995;152(4 Pt 1):1382-1386.

Hoyte FC. Vocal cord dysfunction. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. Feb 2013;33(1):1-22.

Bucca C, Rolla G, Scappaticci E, et al. Extrathoracic and intrathoracic airway responsiveness in sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Jan 1995;95(1 Pt 1):52-59.

Kenn K, Balkissoon R. Vocal cord dysfunction: what do we know? Eur Respir J. Jan 2011;37(1):194-200.

Kapnadak SG, Kreit JW. Stay in the loop! Ann Am Thorac Soc. Apr 2013;10(2):166-171.

Low K, Lau KK, Holmes P, et al. Abnormal vocal cord function in difficult-to-treat asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Jul 1 2011;184(1):50-56.

Reisner C, Borish L. Heliox therapy for acute vocal cord dysfunction. Chest. Nov 1995;108(5):1477.