Written by: Aldo Gonzalez, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Jason Chodakowski, MD (NUEM '20)

Expert Commentary by: Mike Macias, MD

Hand Nerve Blocks

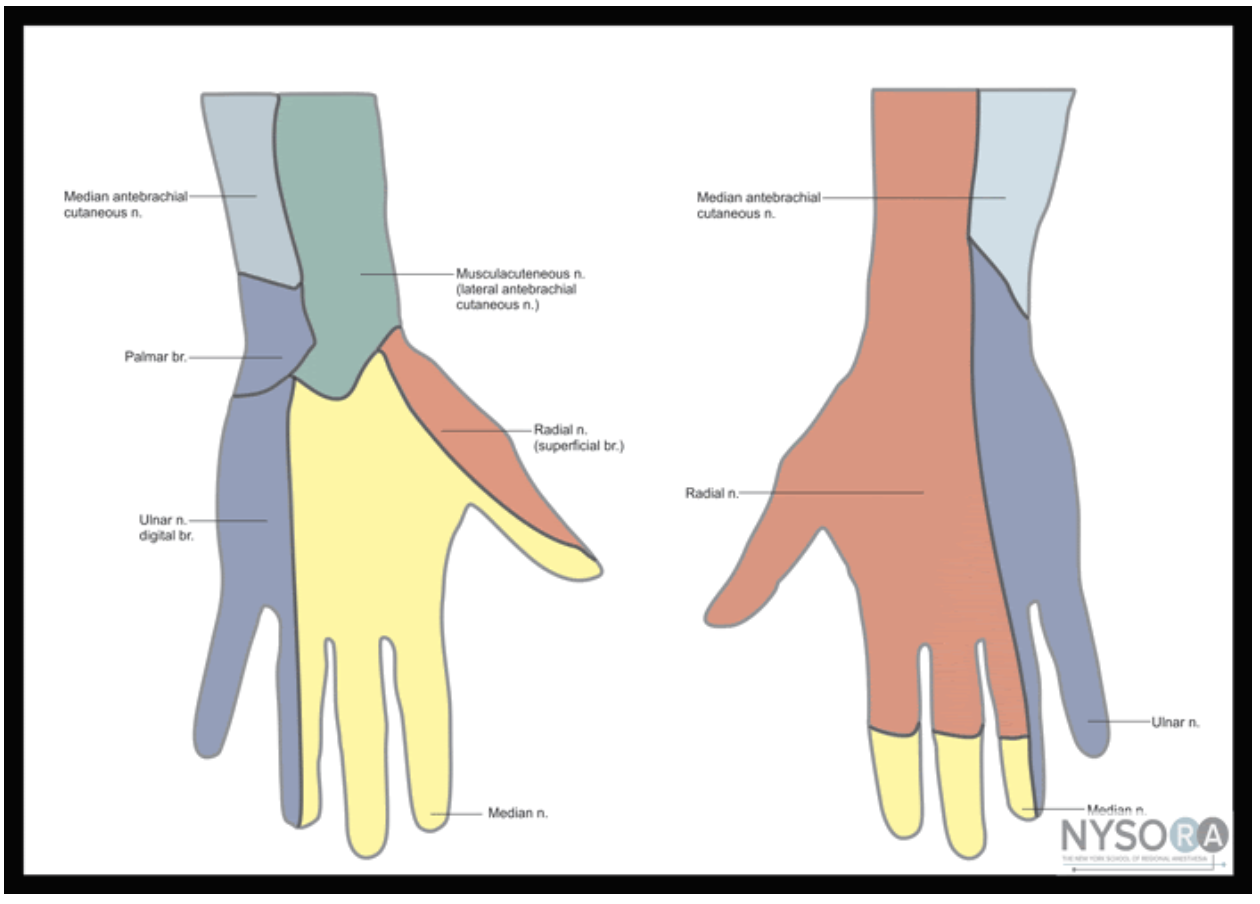

Nerve blocks are the use of anesthetics to anesthetize an area by injecting directly around the nerve that innervates a certain area. It is useful when there is a large area to provide anesthesia, the area might get distorted by local infiltration and make it difficult to close the tissue, or the distribution of the area to be anesthetized is well-suited to a nerve block.

Indications

Nerve blocks of the median, ulnar, radial, and digital nerves are useful for injuries of the hand including fractures, lacerations, and burns.

Contraindication

Overlying infection

Previous allergic reaction to anesthetic

Anesthetics

Landmark versus Ultrasound guidance

Ultrasound guidance is preferred given the ability to visualize the desired nerve and proper instillation of the anesthetic around the nerve. On ultrasound nerves are circular or triangular hyperechoic structures with hypoechoic structures within. Often described as having a “honeycomb” appearance as seen in the image of the median nerve below.

Materials

Ultrasound with Linear Transducer

Probe Cover

Sterile Ultrasound Gel

Anesthetic

10 cc syringe

18 gauge needle (to draw medication)

25-27 gauge needle at least 1.5 in in length

Antiseptic Solution (ex. Chlorhexidine)

Towel

Positioning

The patient can be either supine or seated with their arm slightly abducted and rested on a flat surface. Their elbow can be flexed with the wrist supinated and in slight extension. A rolled towel can be used for patient comfort and help in maintaining slight extension.

Figure 1: Nerves, arteries, and muscles of the human forearm

Radial Nerve Block

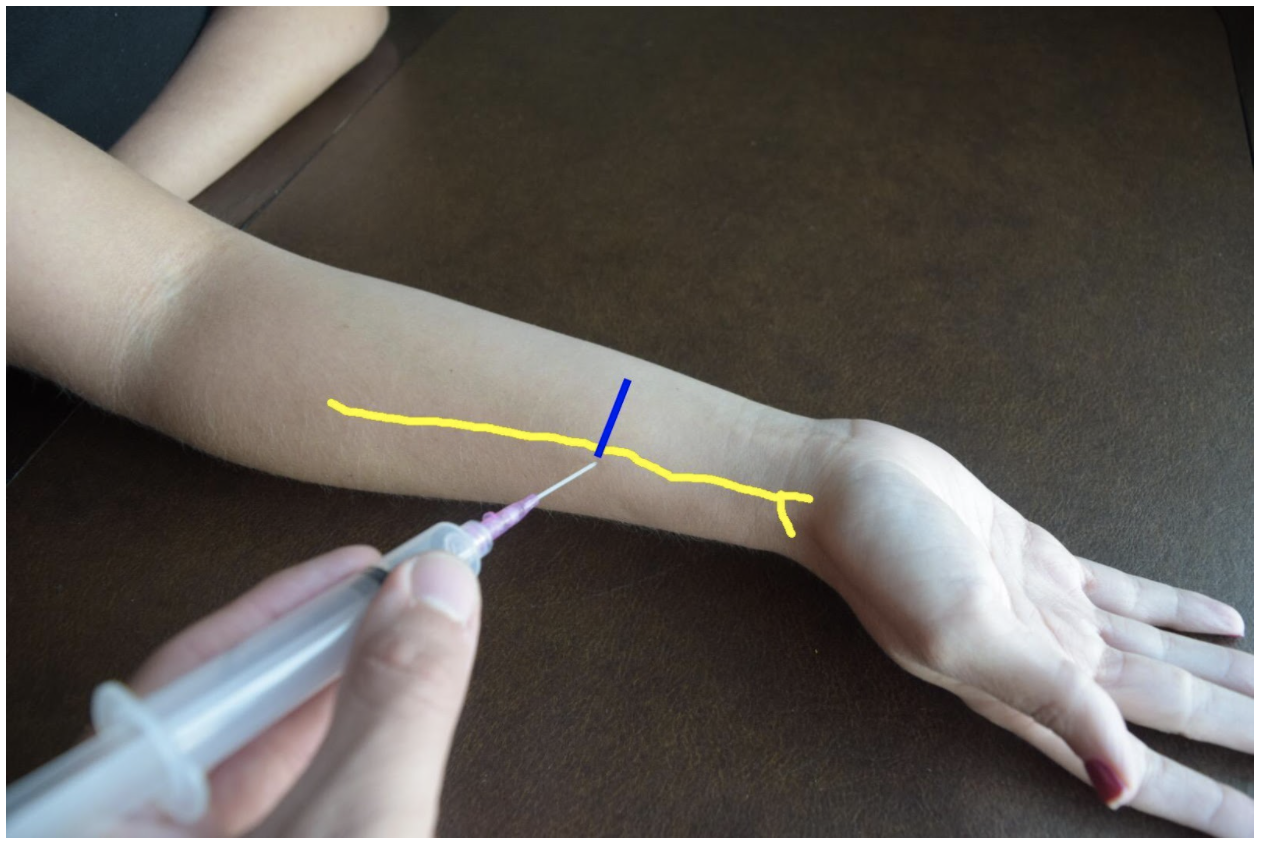

The superficial radial nerve travels between the flexor carpi radialis and the radial artery on anterior (volar) and lateral (radial) aspect of the forearm. Near the wrist the radial nerve splits into the medial and lateral branch of the superficial radial nerve. The block of this nerve should be performed at the mid-forearm to distal third of the forearm before the nerve splits. The nerve may be difficult to see at the distal forearm so instead it can be found proximally and followed distally. A lateral (radial) approach of the forearm provides the most direct route to the nerve.

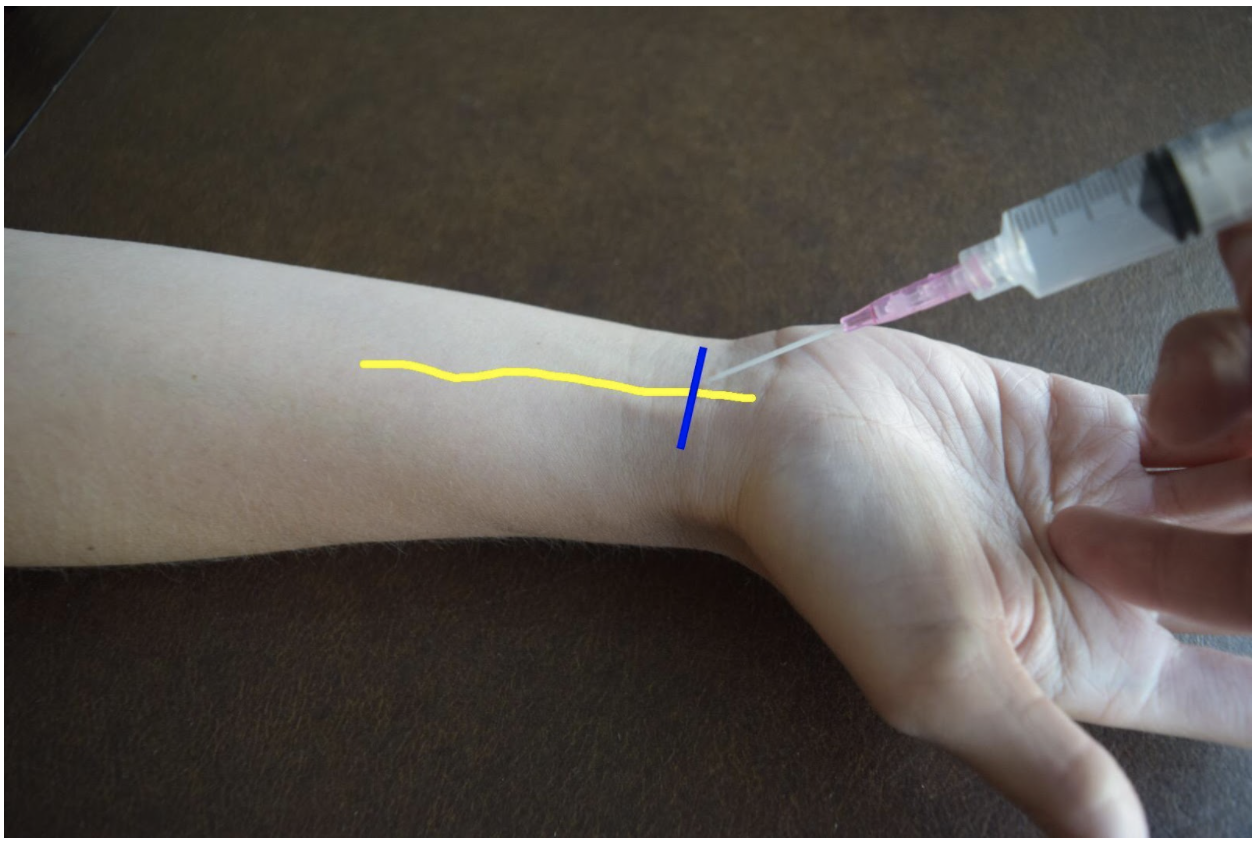

Figure 2: Demonstration of a radial nerve block using a lateral (radial) approach with in-plane ultrasound technique on a patient’s right hand. Radial nerve (yellow line) and ultrasound probe location (blue line).

Ulnar Nerve Block

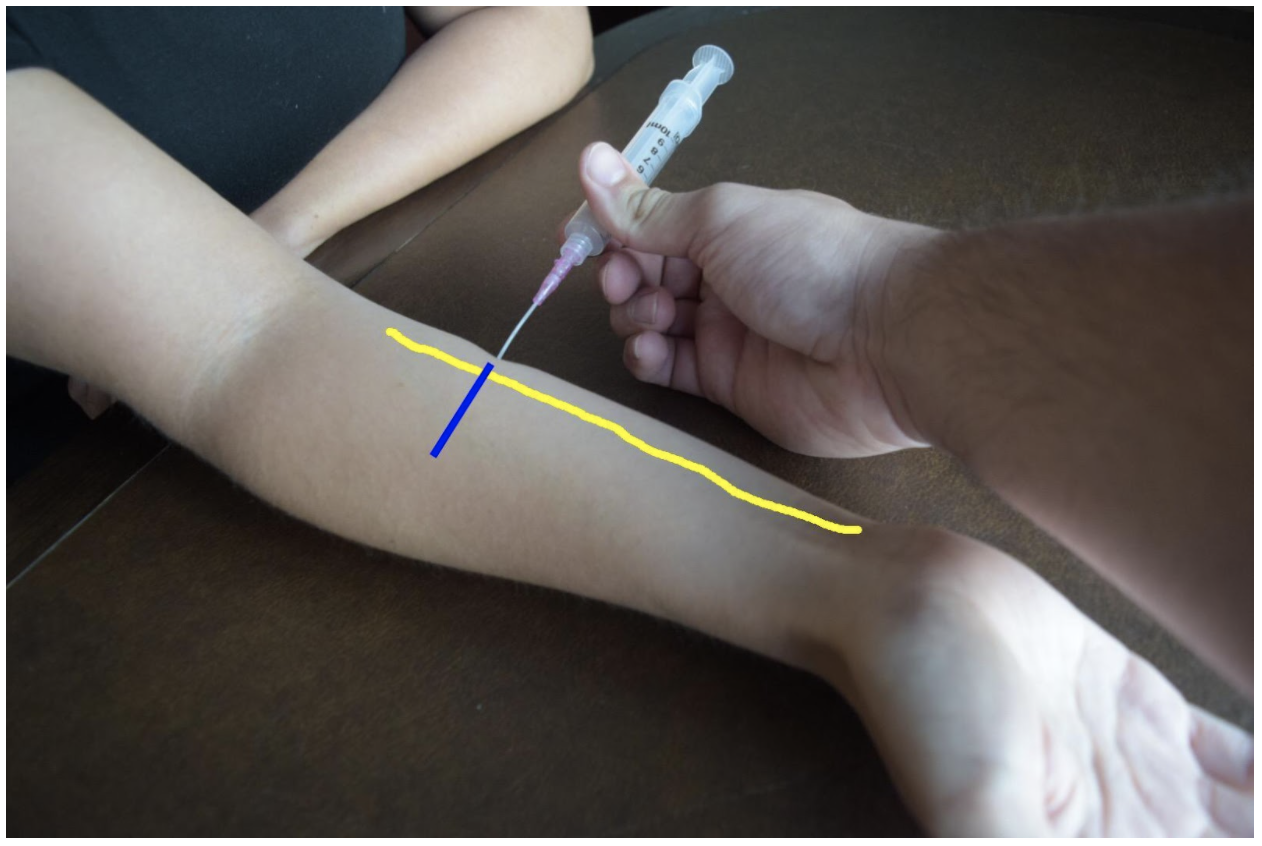

At the distal forearm the ulnar nerve runs on the medial (ulnar) and anterior (volar) aspect of the forearm between the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and the ulnar artery. The ulnar nerve lies in very close proximity to the ulnar artery in the distal forearm and increases the risk of accidental intravascular injection. It is safer to identify the ulnar nerve distally and the follow the artery and nerve proximally. Around the proximal third of the forearm the ulnar artery dives deeper and separates from the ulnar nerve. This provides a safer target. A medial (ulnar) approach of the forearm provides the most direct route to the nerve.

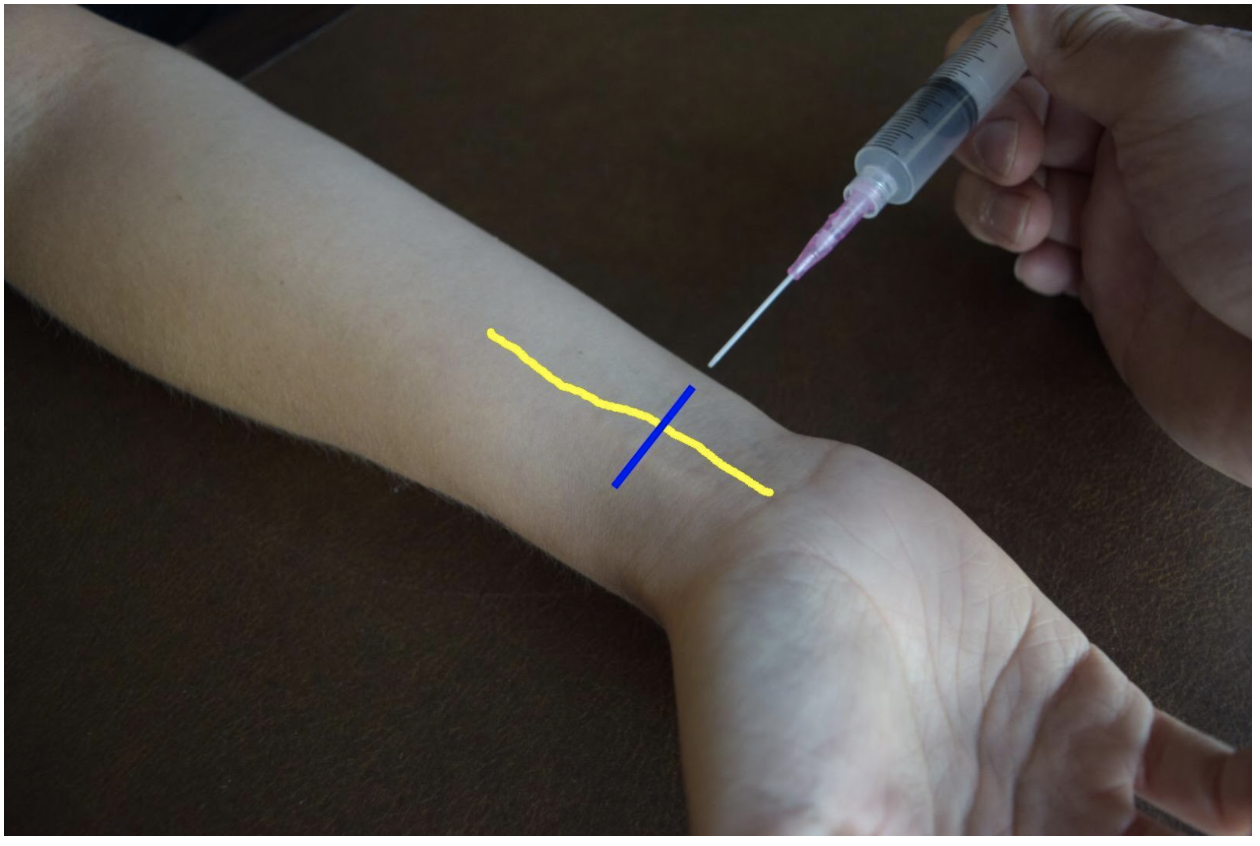

Figure 3: Demonstration of an ulnar nerve block using a median (radial) approach with in-plane ultrasound technique on a patient’s right hand. Ulnar nerve (yellow line) and ultrasound probe location (blue line).

Median Nerve Block

At the mid to distal forearm the median nerve runs in the middle of the anterior (volar) aspect of the forearm between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus muscles/tendons. Near the wrist the nerve can be difficult to appreciate due to all the tendons of the anterior compartment of the arm. The nerve can be best appreciated at the mid-forearm. A lateral (radial) or medial (ulnar) approach can be used for in-plane technique or a mid-line approach using out-of-plane technique. Be mindful to avoid accidentally puncturing the radial or ulnar artery If using an in-plane technique with a lateral or medial approach.

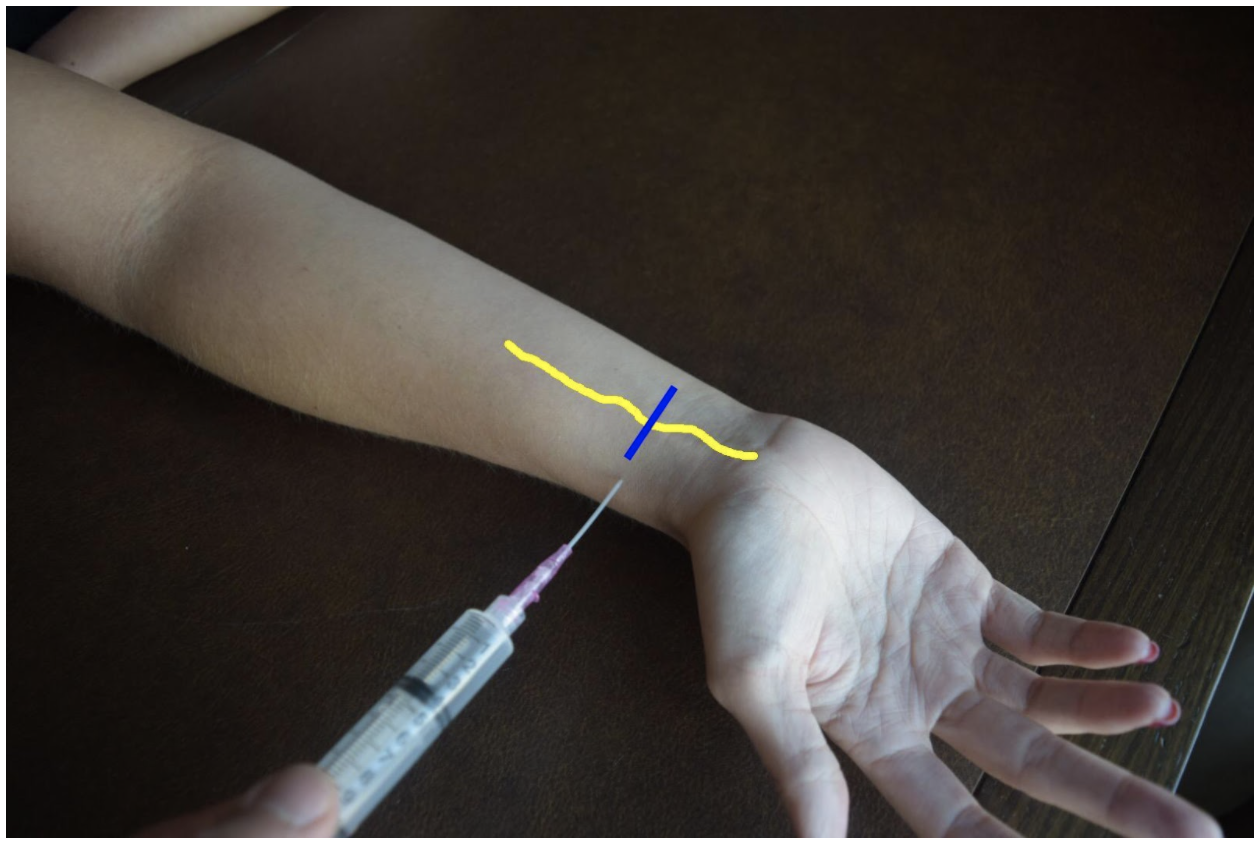

Figure 4: Demonstration of a median nerve block using a midline approach with out-of-plane ultrasound technique on a patient’s right hand. Median nerve (yellow line) and ultrasound probe location (blue line).

Figure 5: Demonstration of a median nerve block using a median (ulnar) approach with in-plane ultrasound technique on a patient’s right hand. Median nerve (yellow line) and ultrasound probe location (blue line).

Figure 6: Demonstration of a median nerve block using a lateral (radial) approach with in-plane ultrasound technique on a patient’s right hand. Median nerve (yellow line) and ultrasound probe location (blue line).

Steps for Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Block

Document a neurological exam prior starting the procedure

Select the nerve or nerves best suited to achieve best anesthesia for the injury

Use the linear transducer to visualize the nerve prior beginning the procedure

Plan an approach and select the best site

Draw up anesthetic in the 10 cc syringe with an 18 G needle

Replace 18 G needle with 25-27 G needle

Use antiseptic solution to prepare the skin

Dawn sterile gloves

Cover transducer in sterile cover

Use ultrasound to visualize the nerve and confirm approach

Insert the needle into the skin

Advance the needle using in-plane or out-of-plane technique

Come close to the nerve but do not puncture the nerve

Draw back to confirm not with-in a vessel

Deliver 5mL of anesthetic

The nerve will become enveloped in hypoechoic anesthetic and peel away from the fascia of nearby muscles

Withdraw the needle.

Wait 3-5 minutes until patient is fully anesthetized

References

Drake, R., Vogl, A. W., & Mitchell, A. W. (2015). Gray's Anatomy for Students (3rd ed.): Elsevier.

Farag, E., Mounir-Soliman, L., & Brown, D. L. (2017). Brown’s Atlas of Regional Anesthesia (5th ed.): Elsevier.

Gray, H. (2000). Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body. 20th edition. Retrieved from https://www.bartleby.com/107/

Harmon, D., Barrett, J., Loughnane, F., Finucane, B. T., & Shorten, G. (2010). Peripheral Nerve Blocks and Peri-Operative Pain Relief (2nd ed.): Elsevier.

Pester, J. M., & Varacallo, M. (2019). Ulnar Nerve Block Techniques. In StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing.

Roberts, J. R., Custalow, C. B., & Thomsen, T. W. (2019). Roberts and Hedges' clinical procedures in emergency medicine and acute care (7th ed.): Elsevier.

Waldman, S. D. (2016). Atlas of Pain Management Injection Techniques E-Book (4th ed.): Elsevier.

Waldman, S. D. (2021). Atlas of Interventional Pain Management E-Book (5th ed.): Elsevier.

Expert Commentary

Thank you Drs. Gonzalez and Chodakowski for the excellent post on forearm nerve blocks! This is an important skill that definitely improves the care of our patients, especially since hand injuries are such a common emergency department presentation. This is especially true for injuries that are difficult to anesthetize using traditional local injection such as dog bites, burns, abscesses, large lacerations, and fractures of the hand. I’d like to dive a little deeper into a few aspects of forearm nerve blocks:

Ultrasound guidance

I think that the days of a landmark based approach to the majority of nerve blocks are gone with the widespread availability of ultrasound and its superiority with respect to block success and reduced complications. So if you have it, use it!

Which nerve to block?

Once you have made the commitment to block one forearm nerve, it doesn’t require much additional time or effort to block a second or even a third! Often, hand injuries will span several nerve distributions so make sure you are providing adequate anesthesia. Here is a quick way to think of it:

Major hand injury (ie burn, multiple hand fractures): Triple block

Injury to radial aspect of hand or digits 1-4: Radial + median nerve block

Injury to ulnar aspect of hand or 5th digit (ie Boxer’s fracture): Ulnar nerve block

It is important to remember that forearm nerve blocks do not provide anesthesia to the volar forearm or wrist and therefore will not be adequate for distal radius fracture reduction. In this case, an above the elbow Radial nerve block should be performed.

Which local anesthetic should I use?

It’s always important to consider what the goals of your local anesthetic are when determining which one to use. If you are performing a quick procedure, the shorter the better such as lidocaine. If you are providing prolonged pain management such as with a burn, bupivicaine is a better choice. I tend to prefer lidocaine + epinephrine (duration of acton 2-2.5 hours) for most of my hand injuries. Why? In a busy emergency department managing many patients at a time, the initial block and the procedure you plan on performing (ie lac repair, fracture reduction, etc) do not always happen simultaneously (ie patient may still need x-ray, irrigation, ring removal, etc). Using lidocaine + epinephrine will allow you to provide immediate pain relief for your patient but give you time to do other tasks before the patient is ready for the procedure

Positioning

As with any procedure, the set up is extremely important. You nicely described positioning earlier but I just want to highlight a couple additional points. Make sure your patient is comfortable and your ultrasound screen is in-line with your procedure. You don’t want to be turning your head away from your block to look at the screen. For the median and radial nerve block, the patient’s arm should be supinated and resting on a hard flat surface. Both nerves can then be approached using an in-plane technique from the radial aspect of the arm. The ulnar nerve can be cumbersome to get to with this same patient positioning so I recommend abducting the shoulder to about 90 degrees and placing the arm on a Mayo stand next to the patient. This will allow an in-plane approach from the ulnar aspect of the arm. I have also found this positioning technique helpful for the ulnar nerve block.

Procedural Tips

I wanted to end with a couple of important procedural pearls I have learned during my experience with performing these blocks:

Perform a pre-block exam! Always make sure to perform and document a full neurological exam of the hand before you block any nerve. This is important because you want to make sure you know if any sensory or motor changes are present before your perform the block otherwise if a neurological deficit is noted after, it makes it difficult to tell if the block caused the new symptom (you can always wait until the anesthetic wears off but it may be awhile if you used bupivicaine).

Follow the arteries! Sometimes it can be tricky to find the ulnar and radial nerves. The easiest method is to always start distally at the wrist. Both the radial and ulnar nerves run with their paired artery so if you start here and slide proximally, you should see the nerve split away from the artery around the mid forearm. Block them here!

Target the fascial plane! The key to an effective forearm nerve block is “bathing” the nerve in anesthetic. You will want to see spread of the anesthetic around the nerve in a crescent shape, full circumferential spread is not needed. Since these nerves run in the fascial plane the goal is to get your needle tip into this plane to deposit anesthetic. There is never a need to actually touch the nerve so avoid this by aiming for the fascia and not the nerve.

Protect the hand! After you perform a forearm nerve block be sure to communicate with nursing, consultants, and the patient regarding what block was performed and how long the effects will last. If a long acting agent was used such as bupivicaine, the hand should be splinted or arm placed in a sling and instructions provided to patient regarding care at home if they are being discharged.

Thank you again for providing this excellent piece on forearm nerve blocks. I cannot stress enough how essential I think these blocks are to the toolkit of the modern emergency physician. I promise you once you add these to your practice your patient’s will thank you!

Michael Macias, MD

Global Ultrasound Director, Emergent Medical Associates

Clinical Ultrasound Director, SoCal MEC Residency Programs

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Gonzalez, A. Chodakowski, J. (2021, Nov 29). Hand Nerve Blocks. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Macias, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hand-nerve-blocks