Written by: Maurice Hajjar, MD, MPH (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Philip Jackson(NUEM ‘20) Expert Commentary by: Gabby Ahlzadeh, MD

Expert Commentary

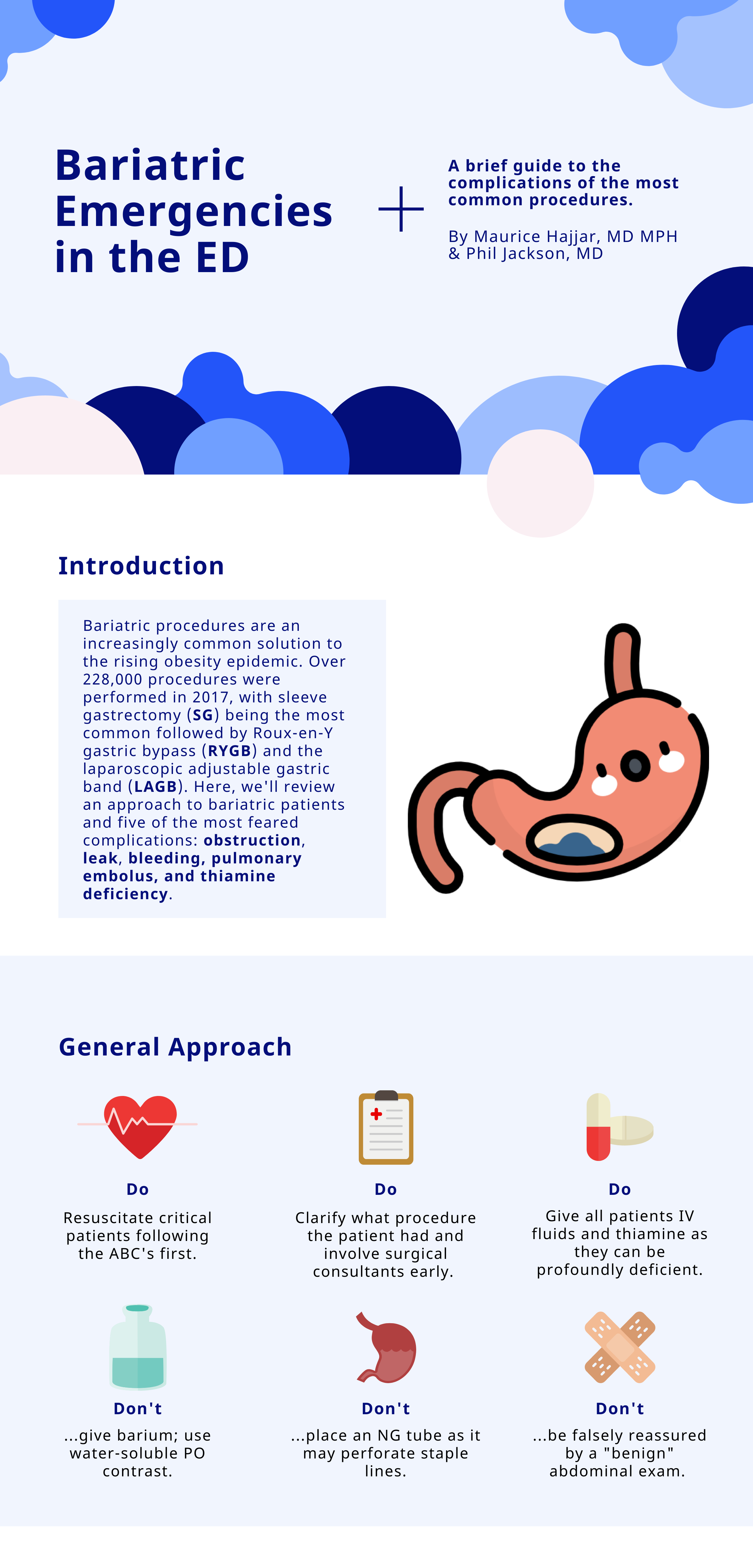

Thanks for this great post. Being familiar with the anatomy of these various procedures is essential to understanding the complications and why you cannot be reassured by a benign abdominal examination.

With laparoscopic band procedures, complications are more common early on and are more related to band erosion or migration. Migration of the lap-band is best evaluated with an upper GI series with Gastrografin. Another important question to ask patients is if their lap band has been inflated recently. This is typically done in a progressive manner, where normal saline is instilled within the subcutaneous port. This can also be a source of obstruction, and if emergent, the band can be deflated by aspirating fluid from the port. This should be done under the guidance of a surgeon, if possible.

Asking about dietary indiscretions can also sometimes clue you in to why a person is having abdominal pain or nausea. Especially immediately post-op, these patients have specific dietary guidelines and are often limited to liquids or pureed foods. Dumping syndrome can also occur in this patient population, more common with gastric bypass surgery, due to rapid gastric emptying. Typically, these patients have bloating, sweating, facial flushing, diarrhea, nausea, early satiety about 30 to 60 minutes after a meal. Dumping syndrome is typically diagnosed clinically, though laboratory testing should be performed to rule out electrolyte derangements. Dumping syndrome is typically treated with dietary modifications and should be discussed with the patient’s surgical team.

As these procedures become more common and advanced, some are also performed endoscopically, which comes with its own set of complications. Another newer procedure is the intragastric balloon, which is a saline filled silicone balloon that is inflated in the stomach. In the first few days after placement, patients may experience abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Other complications include balloon rupture, bowel obstruction, gastric outlet obstruction, gastric ulcer, pancreatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and cholecystitis.

Overall, management of these patients in the emergency department should be done in consultation with the surgeon.

Gabrielle Ahlzadeh, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

University of Southern California

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Hajjar, M. Jackson, P. (2021, Apr 26). Bariatric Emergencies. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Ahlzadeh, G]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/bariatric-emergencies